Who would ever imagine that one of the most established, idolized, coveted star of the Hollywood system would be such a fine connoisseur of one of the most recognized, ingenious, groundbreaking authors of the Italian literature of all times?

Sometimes clichés are walls that need to be torn down. Because, yes, let’s face it: one can be Richard Gere, and at the same time a fine connoisseur of Italo Calvino’s work.

It is however a million-to-one-shot that he happened to share an evening with Giovanna Calvino, the Italian writer’s daughter — and Professor of Italian literature. NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò made this possible by organizing their unique meeting to launch Calvino’s novel The Baron in the Trees (Il barone rampante) in the new translation by Ann Goldstein.

The second novel of the trilogy featuring The Cloven Viscount and The Nonexistent Knight, The Baron in the Trees first came out in 1957 and tells the story of an 18th century aristocrat, Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò, who rebels against his family, climbs on a tree in the garden of his house and spends his life there.

Before introducing the two illustrious guests, Stefano Albertini, Director of Casa Italiana, hails Maria Chiara Zerilli — daughter of legendary Mariuccia Zerilli-Marimò — who was in the theater to attend the event.

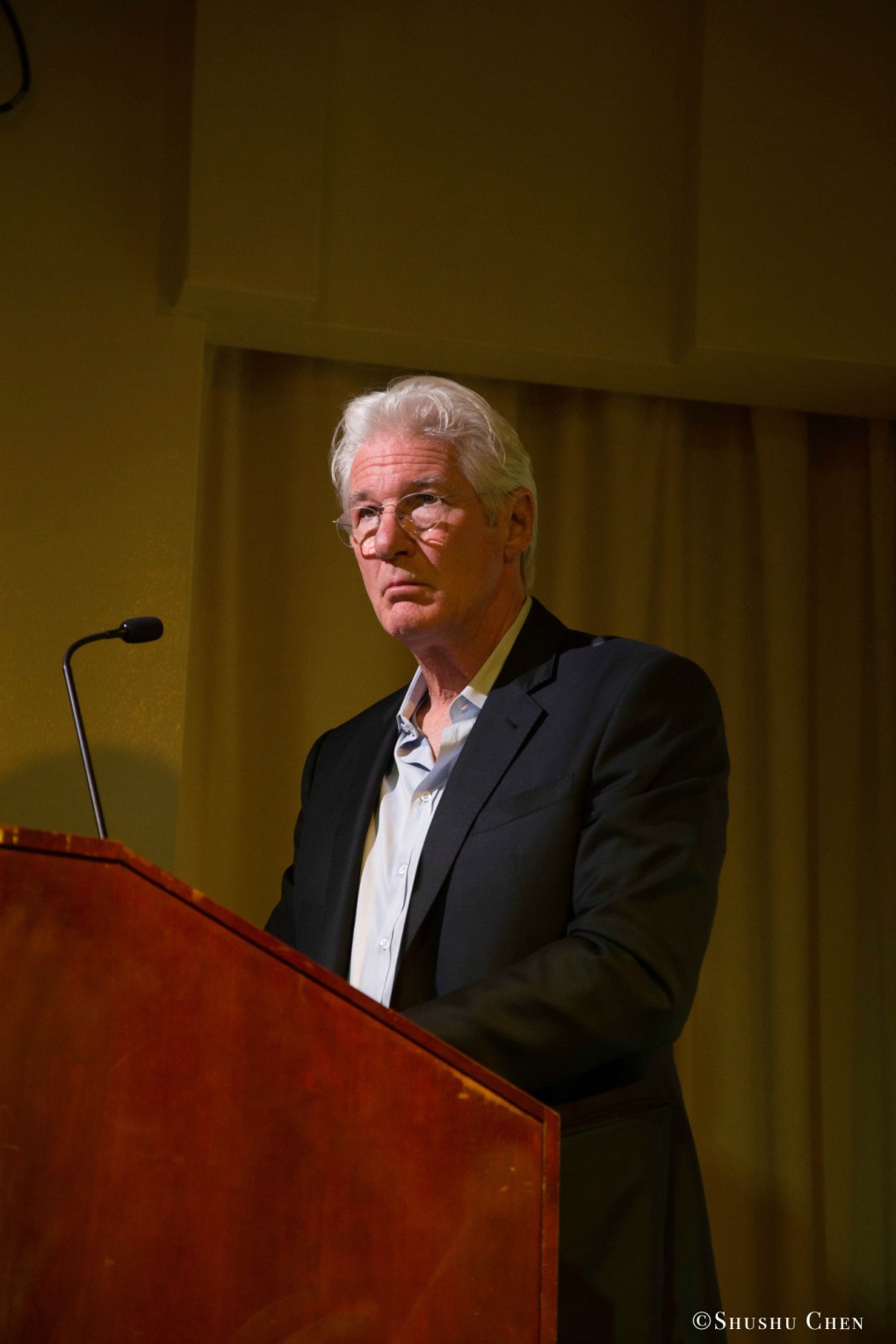

“Actor and activist”, is the way Director Albertini defines Richard Gere. Looking classy, unpretentious and beaming, actor and activist Gere makes his way to the stage and greets everyone with a bright smile on his face. He also waves at people standing along the walls of the theater, and invites them to sit down in a couple of spare seats in the front rows. He is an Officer and a Gentleman, after all…

“I am here to honor Italo Calvino and his talent”, says Gere, proudly. “I wish I could read in Italian”, adds humbly.

After reading from the first chapter of The Baron in the Trees, Director Albertini voices out the first question that has been bouncing in everyone’s head since the very beginning — and heads were definitely numerous, both in the sold-out theater in the basement and in the library on the second floor, where the event was live-streamed.

How happens Richard Gere reads Calvino?

Gere answered generously to the question — with that same generosity, he would answer to any question to follow.

“I first heard about the novel when a dear friend of mine, Jonathan Cott, brought it to my attention. Jonathan — who happens to be here and would hate me if I’d point him out — wrote a script based on the novel, for Louis Malle. I read the script, and found it beautiful. Then I read the novel, and loved it. It has a picaresque feeling… And timelessness. It is saturated with generosity of spirit. It embraces the reader.”

Albertini asks the second question that is now crossing everyone’s mind. “What is preventing you from making the movie based on the novel?”. Gere smiles and shouts. “Chichita!”.

Chichita is Calvino’s wife, Giovanna’s mother. “Chichita is a piece of work! Jonathan came out with this idea of setting the movie in America. It seemed to me it would have been even richer if the story would be set in America. It would have been crazier — the Baron as a sort of Tom Sawyer… Crazy as America is, as New York is: you drive few minutes away from the city and you are right in the woods, surrounded by trees… So please help me with Chichita. Say all together ‘Please Chichita, please!’”, Richard, playfully and ironically, begs the audience to help him convince the woman. And the audience “please” along.

An experienced moderator, Albertini does not neglect Giovanna Calvino, whose resemblance with her father is striking — same delicate features, same piercing eyes. “Your father love’s for trees… Does it have to do with your family ancestors?”.

Although she would later confess that she has always shied away from speaking about her father in public, she returns detailed answers to any query. “My father would not talk about our family ancestors to me. His mother came from a very tiny village in Sardinia and was a botanist. His father was an agronomist. They both lived for trees. My grandfather used to know every name of every leaf of grass around. They were proto-environmentalists. And the garden where my father grew up was full of many species of trees.”

Going back to Calvino’s production, Richard Gere sounds eloquent, savvy, sophisticated in the way he associates the writer’s work to other masters of international literature, and in the way he articulates his own opinions.

“Someone gave me the Italian Folktales when I was in my mid 20s. There is something about Marquez in Calvino’s world, and Borges too. They all had unfettered imagination, which brings you in dark places. The Folktales are dark, and challenging… There is also strictness in Calvino. He labored on every word — he is no Jack Kerouac. The Baron in the Trees is the world I would like to live: the world of dreams instead of nightmares. That’s the reason a movie drawn from that story would be loved. It would be G-rated! Everyone could relate to it, children especially.”

Regarding the dissent of her father towards Fascism, Giovanna comments: “My father grew up during Fascism and as a reaction he became an idealist, a Communist. But he did not make heroes out of the Partisans. And for this reason he was criticized. When he wrote The Baron in the Trees, he was also criticized for being childish. They called him ‘mad’. No wonder he left the Party…”. About the supposedly political aspect of the novel, Gere comments: “It is not a political novel. I’d say it is human. It is a humanist document, where animals, trees, human beings live together.”

The dialogue between Gere and Giovanna Calvino goes on smoothly, with the latter elaborating on her father’s spirituality. “I had the impression that my father was deeply anti-clergy. But his books are spiritual, and there is some pantheism, even Buddhism, I would say, in them. He looked for transcending the ego. That’s why probably he was criticized too. Who looks for transcending the ego?”, asks Calvino, rhetorically. Gere agrees and adds, “Indeed! And he uses the term ‘emptiness’, which is also a Buddhist concept. There is no anger in Calvino’s work. It is, instead, inclusive.”

Being himself a fervent Buddhist, Gere knows what he is talking about. “From the Buddhist point of view, you do the work within yourself. You liberate from the selfishness. And then you can see love, inclusion. But it all starts with the work in yourself.”

After reading the second excerpt from the novel, the actor shouts, “Such good writing!

Such a good translation!”. And Giovanna takes the chance to praise the new translation by Ann Goldstein. “To translate anew is a bit like giving a new voice to a book, which never grows old, unlike translations, which do grow old.”

At this point we also learn that an Hollywood star even knows about translation, and even quotes the forefather of translation studies, George Steiner — second cliché of the day to fall. “My friend Jonathan once paraphrased Steiner: ‘An act of translation is an act of love. Where it fails, through immodesty or blurred perception, it betrays. Where it succeeds, it incarnates.’”

When interrogated on the ongoing situation in America, Gere rolls his eyes and looks hopeless, like everyone in the audience — everyone in the country? “Nobody has ever seen something like this before. It’s all wacky ridiculous… We have to take responsibility for this man not to be elected again”.

A couple of hours has just flown by. You would want more and more, but it is time to leave.

Apparently a Hollywood star and a daughter of a master writer can come up with such an unexpected chemistry that an ordinary October night turns into a recollection to be cherished and told.

Well, as they say, everything is possible in New York City.