On May 1, for NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò’s program “Tutti a casa”, we interviewed historians William J. Connell (Andrew Carnegie Fellow and La Motta Endowed Chair in Italian Studies, Seton Hall University) and Stanislao G. Pugliese (Professor of History and Queensboro UNICO Distinguished Professor of Italian & Italian American Studies, Hofstra University). You can see that interview in the video below, with an introduction by Prof. Stefano Albertini. It was conducted in Italian and it was motivated by the publication of the Italian Edition of the book The Routledge History of Italian Americans (Storia degli italoamericani, Le Monnier).

Here we present a more comprehensive version of the same interview, this time in English. In this, the two editors of the volume that includes essays written by numerous academics, offer their answers in English to the same questions, but this time elaborating on their opinions more extensively.

First of all, let’s try to get a better understanding of how this incredible volume came about. For the first time, we have a work of various authors on the history of Italians in America that embraces five centuries, in which each chapter’s author is deemed to be an expert on various periods or academic disciplines. Is that correct?

William J. Connell: “We of course have to thank each of the nearly 40 writers who contributed to what is a remarkably readable and coherent book, as well as the charitable foundations of UNICO National and Club Tiro a Segno who provided financial support. Maddalena Tirabassi deserves warm gratitude for her work with us as editor of the new edition in Italian. Three of our authors, Francesco Durante, JoAnne Ruvoli and Robert Viscusi unfortunately passed away in the last three years, and each was crucial as the volume developed. There are a number of factors that came into play in putting the project together. First of all, Stan and I felt the need for a history of Italian Americans that was academically rigorous rather than repeat old stories and ethnic fables (however charming or tragic they might be), and that paid attention to the broad range of the Italian American experience. Second, the field of Italian American Studies has been a growth area in universities in the US and also in Italy, but in the past scholars in Italy and the US often followed divergent agendas with respect to the Italian diaspora, and this was a way to bring them together. Third, we needed a good textbook to assign our students—many of whom are now wondering what significance the term “Italian American” has today, and whether it will have meaning in the future. Fourth, we wanted to model the project on the great collaborative histories produced in Italy—most notably by Einaudi and UTET—and this offered a way to bring together the significant approaches and discoveries of a warm and supportive community of impressive scholars. One last observation. There is a risk in the study of any ethnic group that it becomes self-absorbed—that a kind of omphaloskepsis takes over, with only Italian Americans studying Italian Americans, so that within the academy there can be a kind of ghettoization. We think Italian Americans have a history that should generate serious interest on the part of anyone who cares about the history of the United States, of Italy, of immigration, of globalization and of many other topics. For my part, I happen not to be Italian American—the name Connell is Irish—but I think it’s an important and fascinating field to work in”.

Stanislao G. Pugliese: “Bill recognized the need for such a book and deserves the credit for convincing UNICO National and the Tiro a Segno Club of its relevance. The subject matter is so vast and the scholarship now so plentiful that no one person could possibly be qualified to write a book on this scale by themselves. Hence the collective nature of the project. The three dozen contributors were extraordinary in working with us, accepting suggestions and meeting deadlines with a professionalism and dedication that were really inspiring. Italian American Studies have now reached a point where we must engage with our colleagues in other disciplines. Having established the foundation for our own field, we can now invite a dialogue with our colleagues in other areas such as gender studies and labor studies with an understanding how history is the underlying and indispensable foundation for all future scholarship”.

This interview takes place on May 1st, which is Labor Day in Italy: many Italians in Italy don’t know that Italian Americans were the protagonists of the labor union movement in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the US, Labor Day is no longer celebrated on May 1st, but in September. Yet, at that time, the fight for labor rights saw Italians in America front and center in organizing strikes. Why were Italians among the major protagonists in the struggle for labor rights in the US?

WJC: “It is true that through much of the world the first of May is celebrated as Labor Day. In the United States, in the late 1800s, this was also true. But after the tragedy in Chicago at Haymarket Square in which 17 labor protesters were killed by police on May 4, the fact that the dates were so close together frightened the authorities, who worried that a May 1 celebration would in effect memorialize the Haymarket “martyrs.” So the government placed Labor Day in this country at the start of September, a “neutral” day that was explained as being equidistant between Independence Day (July 4) and Thanksgiving (at the end of November). As for the role of Italian Americans in the labor movement, in the early years of immigration, let’s say between 1880 and 1890, it so happened that large numbers of newly arrived Italians were employed as “scabs” (crumiri)—as strikebreakers. Agents would enlist them in places like New York or Boston and then send them without much explanation to places in the hinterland—to mines and factories—to do work where the regular employees were on strike. In the 1890s, however, with the arrival from Italy of socialists and anarchists, the so-called “sovversivi”, who are described by historian Marcella Bencivenni, these immigrants provided leadership and know-how they had already acquired in Italy, and they could speak (and publish newspapers and reviews) in the Italian language, so that large numbers of Italian American workers became organized. Once this happened, Italian American workers were quite effective in unions and their leaders became prominent in the labor movement”.

SGP: “Contrary to what was previously thought – that the Italians arrived in the US without any political consciousness – we know Italian migrants came from a rich tradition of social and political activism. This was contrary to Edward Banfield’s thesis that southern Italians were crippled by what he called “amoral familism.” They had been members of peasant leagues and agrarian cooperatives, Catholic mutual aid societies, the CGL (Confederazione Generale del Lavoro) and active in the socialist and anarchist movements. Carlo Tresca was the most famous and flamboyant and Sacco and Vanzetti were the most tragic. But there were many others, including the Italian American women who had a very active role. May Day in America came to be associated with these radicals; hence the decision to move the holiday to September, in an effort to make it more “American” and less radical”.

Is it true that Italians were among the most violent groups during those union struggles? That they planted bombs? What about the tragic story of Sacco and Vanzetti and their death sentence: were the two anarchists completely innocent? Did they pay for the acts of others?

WJC: “Society in general was much more violent than it is today. Sacco and Vanzetti were anarchists. They belonged to a group that adhered to the ideas of Luigi Galleani, who believed in “propaganda of the deed”, and who published a bomb-making manual titled La salute è in voi!, where salute means salvezza (salvation). In other words, “You can save yourselves by making bombs!” The Galleanisti were responsible for a series of bombings aimed at Establishment figures, including an explosion on Wall Street that took 38 lives in 1920. Sacco and Vanzetti were associated with these anarchists. But there is very good reason to believe that Sacco and Vanzetti were not guilty of the robbery in Braintree, Massachusetts they were accused of. Instead they appear to have been framed on account of their political beliefs. And their Italian origin only made matters worse”.

SGP: “Anarchists were the feared terrorists of society before World War I and targeted heads of state. Gaetano Bresci (an Italian anarchist who lived for some time in Paterson, New Jersey) assassinated Italian King Umberto I in 1900. (A year later, American President McKinley was assassinated by a Polish anarchist.) There were actually two schools of anarchism: the more “philosophical” one led by Enrico Malatesta, who denounced political terrorism, and the more violent faction led by Giuseppe Ciancabilla and Luigi Galleani. The Galleanisti subscribed to the belief that the bourgeois capitalist order would always resort to violence to protect its interests, so violence in the cause of its overthrow—“propaganda of the deed” — was justified. Sacco and Vanzetti were not anarchists when they arrived from Italy. It was their experience in America that acted as a catalyst for them to join the Galleanisti. Whether or not they were part of the crime they were accused of – the robbery of a shoe factory and murder of a guard – it is beyond dispute that their trial was a mockery of justice”.

From being great labor rights activists, all of a sudden with the advent of Fascism in Italy, many Italian Americans rallied behind Mussolini and the Blackshirts. Why is this? How did Mussolini manage to have so much success among Italian Americans? And this “admiration” for him — why has this remained so alive in Little Italy?

WJC: “If there is one moment that crystallizes how Italian Americans felt about Mussolini at that time, it is what happened during the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933, when one of Italy’s Fascist leaders, the charismatic aviator and minister Italo Balbo, flew 24 seaplanes in strict formation across the Atlantic and they landed one by one on Lake Michigan in a powerful demonstration of Italian technological capacity and precision. For Italian Americans in Chicago, who were then subjected to the worst possible stereotyping in what was Al Capone’s Chicago, where the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was still freshly remembered, this became a magical, liberating moment, that was then memorialized when a lakeside avenue was named “Balbo Drive”. In the years since World War II, when Fascist Italy declared war on the United States, there have been multiple attempts, some quite recent, to change the name of the street. But none have succeeded”.

SGP: “Fascism represented what I call an “ideology of compensation” for Italian Americans. After having been denigrated and scorned by Americans, told they were no more than organ-grinders and gelato sellers, they readily took to Mussolini’s claim that they were the twentieth-century descendants of the Roman Empire. Many Italian Americans looked approvingly on the Lateran Accords with the Roman Catholic Church. They sent in their gold weddings rings to help finance the invasion and conquest of Abyssinia. They beamed when Mussolini declared an “African Empire” in May 1936. Mussolini cunningly manipulated Italian Americans, preying on their precarious position in America. I think the tide of public opinion may have shifted when Fascist Italy supported Franco in the Spanish Civil War. And the indefatigable work of Italian American radicals and exiled fuorusciti like Gaetano Salvemini and Arturo Toscanini helped in the fight against fascism. Today, there is still a segment of Italian America that longs for Mussolini. This I call the “culture of nostalgia.” They argue – still! – that “Mussolini made the trains run on time” and “Mussolini did a lot of good things; his only mistake was taking up with that mascalzone Hitler” (!)

Let’s discuss the mutual aid associations: originally, many of them were created at the end of the 19th and 20th centuries to assist immigrants who were arriving to America and didn’t speak a word of English. As time passed, these associations either disappeared or became even more powerful, but also much more conservative; lobbies that attract successful and powerful Italian Americans. Is this so? Why?

WJC. “The phenomenon of associazionismo in both Italian and Italian American culture requires a major study. In Italy I think immediately of religious confraternities, masonic lodges, Rotary Clubs, and cycling clubs among other things. In the United States the associazioni di mutuo soccorso of the late 19th and early 20th centuries tended not to be networked but rather located in specific neighborhoods of Little Italies where Italians from the same town or region settled creating not so much “Little Italies” as Little Sicilies (New Orleans), Little Perugias (the Chambersburg section of Trenton, New Jersey), etc. There is a change that occurs when the Order Sons of Italy in America (which only recently became the Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America) was founded to create a national network of lodges. UNICO National was founded 1922 in Waterbury, Connecticut—a town graced since 1909 with a beautiful replica of Siena’s Torre del Mangia—when several Italian Americans were denied membership in the local Lions Club. There are still many small local organizations—”social clubs” they are called– but the large national organizations (I should also mention the National Italian American Foundation, NIAF) attract politicians to their conventions. It is also true that these organizations have memberships that trend conservative and Republican, but they are not political clubs. Fundamentally these are organizations that are charitable and patriotic. Many of the members are instead Democratic. In 2000 Bill Clinton gave the major speech at the NIAF convention: I remember it well because the White House speech writer called me for advice on what to say. Barack Obama addressed the NIAF convention in 2011….It’s interesting that Donald Trump hasn’t yet”.

SGP: “Some I-A mutual aid societies in the US were brought over from Italy; some were indigenous to America. With the passage of time and assimilation, they became less necessary. Other organizations, such as the Order Sons of Italy in America, took their place at a national level. Both the local mutual aid societies and the national organizations were inherently “conservative” in the best sense of the term: they were created with the express purpose of preserving Italian culture. That project of cultural conservation morphed into political conservativism. As Italian Americans became more assimilated into American society, they absorbed the ethos of political conservativism, especially as they moved from the urban Little Italies to the surrounding suburbs. But let’s not forget that for every Antonin Scalia, there is a Mario Cuomo”.

Italians and show business: How much have Italian Americans contributed to the success of Hollywood with their great actors, directors and performers? And does Hollywood hold any responsibility for its portrayal of the stereotypical image of Italian Americans as being uncivilized, violent, mobsters — which unfortunately is still the image that prevails among many Americans?

WJC. “One of the chapters in our book, written by Giuliana Muscio, describes the back-and-forth between Italy and the United States in way that is quite compelling. One especially interesting fact is that a substantial share of the movies that were shown in Italy in the early years were produced in the United States by Italian immigrants. The movies shot in Hollywood were directed at bourgeois audiences in Italy. The movies shot on the East Coast, at a major studio in Newark, for instance, were instead largely Neapolitan productions in dialect, characters and plots. As for the importance of Italian Americans in the film industry there is of course a long honor roll of performers (Valentino, Sinatra, De Niro, Pacino…) and directors (Capra, Coppola, Scorsese…). The movies have always been fascinated with mobsters. There’s nothing new in that. An important moment was undoubtedly in the 1970s, when instead of non-Italian actors playing Italian bad guys like Al Capone, Italian American actors began playing them. They were really good actors and some of the movies were really good too. It’s true that the better the movie and the better the actor, certain representations tend to stick in the mind. But there was already an exaggerated fear of the organized crime of Italians that began spreading much earlier in American society, about the time of the investigative hearings of Senator Kefauver that were televised in the early 1950s. If you listen to one of the most famous radio shows of the 1940s, Life with Luigi, there are no references to organized crime at all. But in the 1950s the stereotyping returns.

SGP: “Here I would recommend two books: Giuliana Muscio’s Napoli/New York/Hollywood and Mark Rotella’s That’s Amore. Italian Americans were critical in developing the entertainment industry, often alongside fellow Jewish immigrants. For all that influence, they could not deter the deeply rooted stereotypes of the mafioso, the Latin lover (Valentino) and the “cafone.” It may be that these stereotypes fulfill some deep-rooted psychological need – like the myth of the cowboy that is so essential to American history – that it is almost impossible to stamp them out. Maybe a better strategy is to engage them and make a distinction between great works of art and exploitation. And to support films that portray Italian American culture in a more realistic manner, such as Edward Dmytryk’s “Give Us This Day” (1949, based on Pietro Di Donato’s Christ in Concrete), Nancy Savoca’s “Household Saints” (1993), Dominique Deruddere’s “Wait Until Spring, Bandini” (1989, based on John Fante’s novel), Stanley Tucci’s “Big Night” (1996), and John Turturro’s “Mac” (1992).

Here is a piece of good news: Leonardo di Caprio is going to produce and act in a movie that will recount the story of Joe Petrosino to the American public. What do you both think about this? Will it assist in providing an image of Italians in the US which is more in line with their contributions to society?

WJC: “Perhaps. But you have to keep in mind that the criminals Petrosino was pursuing were Italian—they were Black Handers. Petrosino was a great hero. He was like Falcone and Borsellino who because they knew Sicily so well were able to get a handle on the Mafia. Petrosino was a New York cop who wasn’t Irish like most of the others. He knew Little Italy like the back of his hand. And, of course, he was assassinated in Palermo—like a number of other heroes”.

SGP: “Well, it only took more than a century, but Hollywood has finally gotten around to telling the story of Petrosino. This is a most welcome development and we should encourage more projects like it. I’m not sure how effective this will be in dismantling the old stereotypes, especially since Petrosino was assassinated by the Mafia in Palermo. So, ironically, the story may end up reinforcing the problem”.

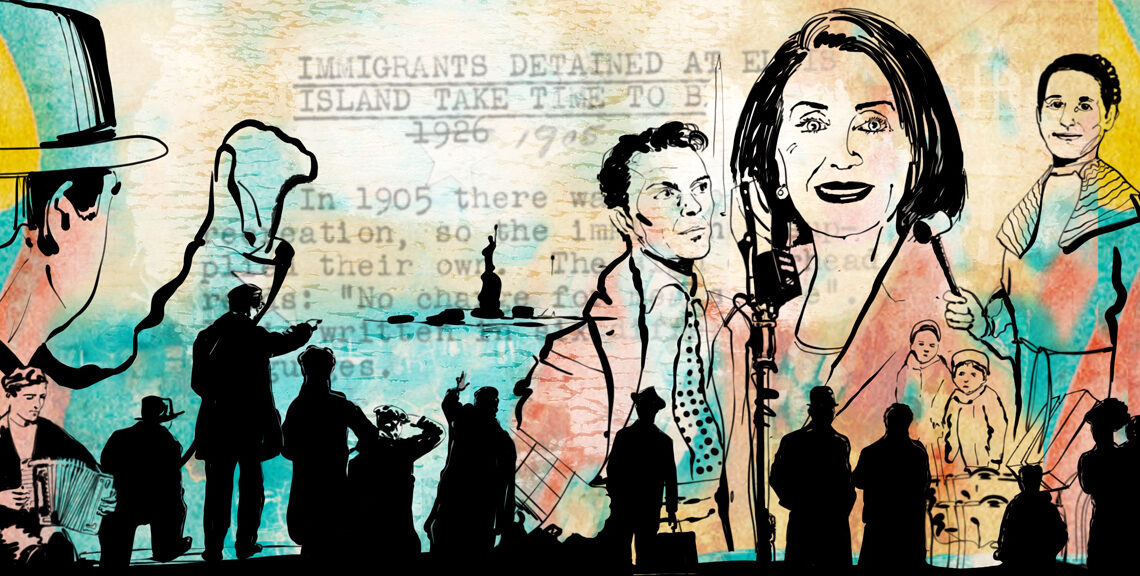

Let’s go back to the topic of politics: Nancy Pelosi and Mike Pompeo have the letter “P” of their names in common and the fact that they are both Italian Americans. But politically, they seem to be very different from each other. And yet, Italian Americans have had great success in politics. Is this due to their way of being, their character and their culture, or is it simply that Italian Americans hold so many powerful positions in politics because they know how to divide themselves among various political forces? In other words, they never formed one political block within one party. Does the White House still remain a taboo for them?

WJC: “In my Introduction to our History, I say that the 1980s was the decade in which Italian Americans really “made it” in American society. Not only in politics (Mario Cuomo), but in law, architecture, medicine, women’s rights, education, the automobile industry. I don’t see it as a tabù with respect to the White House anymore, although it once was. What is instead changing is the idea that “Italian American” matters as a particular identity. Many IAs think of themselves simply as Americans and don’t give much thought to their ancestry now that discrimination has diminished and exogamy is common. One of the things this history tries to do is to show how that identity once mattered and how it has changed over time”.

Judge Ferdinand Pecora, Democratic Party; Mrs. Roosevelt; Acting Mayor Vincent R. Impellitteri, Experience Party; and Edward Corsi, Republican Party. Impellitteri won. Courtesy of Bettmann/Getty Images.

SGP: “The symbolic high point of Italian American political power perhaps was the 1950 NYC mayoral election when all three candidates were Italian American: Ferdinand Pecora (born in Sicily), Edward Corsi, and Vincent Impelliteri (born in Sicily, who won). I don’t think there is anything inherent in Italian American culture that makes for great politicians. And our experience has been such that we range over the entire political spectrum, which perhaps is a good thing. As for the White House: I remember hoping Mario Cuomo would run and my disappointment when he bowed out. While there are still strong stereotypes, I don’t see why an Italian American man or woman couldn’t be elected to the White House”.

Another stereotype of Italian Americans is that families didn’t push their children to getting an education, at least not in the same way that other ethnic groups that were arriving in America did during those same years did. Is this true? And yet, these days when everyone is watching Dr. Anthony Fauci on TV, whom they consider to be the most authoritative scientist regarding the pandemic, don’t they see him also as a son of Italians from Brooklyn? Do you think it’s true that they did not value education or is this just apocryphal? Italians are everywhere, even in the sciences, in academia…

WJC: “In the early years of mass immigration children had to find jobs from an early age. Then there was the phenomenon of trades, plumbing to cite a common example, passing from father to son. But there was also resistance on the part of the educational system. It was the educator Leonard Covello in New York who led the way in showing that Italian American kids, when given the opportunity, could excel. And with success becoming possible Italian families embraced it in the period after World War II. Italian Americans today have a high level of academic achievement”.

SGP:“The reality is a bit complicated. As James Periconi notes in our book, there was a vibrant reading, writing, and publishing culture among Italian Americans. I remember my father trying to learn English by reading the newspaper and an Italian-English dictionary after a day of hard labor. At one point, there were nearly 200 Italian language newspapers in the US. At the same time, the dire necessities of a brutal economic system often dictated that children went to work in sweatshops and factories once they finished elementary school. There may also have been some lingering sentiment from rural Italian culture not to educate your children “too much” lest they be lured away from the family. And there was a pernicious thinking in some quarters that we should strive too hard, because that was tempting fate. So it was good to be a pharmacist, but don’t try to be a doctor. It’s OK to be a teacher but don’t try to be a professor. It took more than one generation to overcome some of these ideas. And of course, there were the cultural stereotypes that while Asians and Jews were “bright”, Italian Americans didn’t measure up. As late as the 1980s, there was a common cultural stereotype that Italian American children were not “up to” the challenge of college work. My wife suffered first hand from this prejudice. Today, she is a professor at Pace University!”

When a friend and colleague of mine, Tiziana Ferrario, who writes a column for La Voce di New York and is a famous correspondent for RAI, found out that we were going to have this interview, she wanted me to especially ask you this question. She wants to know, why is it that Italian American festivals and celebrations still promote what is more a caricature of an Italy that practically no longer exists instead of foregrounding today’s’ modern’ Italy.

WJC: “Well… Actually, I’m not sure what she means by “l’Italia di tanti anni fa”? The Columbus Parade or the NIAF convention usually celebrate Ferrari automobiles or Ducati motorcycles or something along those lines. Those might be considered modern. The people who organize these events, mostly men, but with a few women, are in their 50s to 70s and they remember and glorify the Italy of Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, Marcello Mastroianni…. If she means instead the cucina of tanti anni fa, the zeppole etc., that seems understandable in a popular setting. Slow Food won’t work at the Festa di San Gennaro with tens of thousands of people. But I’m sure if Tiziana Ferrario can introduce them to a wealthy corporate sponsor who represents what she considers to be modern Italy, she will certainly find a hearing! I do remember that the President of one Italian American organization once urged me personally to organize a celebration of the Beretta arms manufacturing company, with pistols on display… I had to say “no” to that”.

SGP: “It is very possible. For some Italian Americans, the Italy they embrace is product of what I called “the culture of nostalgia” above. They imagine some rural and pastoral Italy of their grandparents or great-grandparents. Maybe they think of the Italy of “la dolce vita” after the Second World War. The caricature is comforting, but not realistic. Since most Italian Americans don’t read or speak Italian, they are not familiar with Italy as a modern, complicated, and difficult country. Some people prefer the image of Italy as its presented in travel brochures and restaurant commercials (think Olive Garden) rather than a country struggling with issues like migration, youth unemployment, and corruption. These realities are not to intrude on the celebrations of Columbus Day.”

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: many Italian Americans have become infatuated with Trump. But it seems to me, and here I speak as the Editor of La Voce di New York, that these Italian Americans support his most aggressive anti-immigration policies—against both the legal and illegal immigrants. In other words, the ‘nativist’ ideology that oppressed the earlier Italian immigrants to America. How could this happen? Has it been so easy for Italian Americans to forget the story of their own suffering?

WJC: “I think it’s a shame that “nativism” has so taken hold of many Italian Americans. Sometimes critics accuse them using the phrase “Those who were last to enter, are shutting the door behind them.” But in this case it’s not entry into America per se, but rather that entry into the upper ethnic echelon that I said occurred when Italian Americans “made it” in the 1980s. To be honest, I’m optimistic. I think that in the future there will be sensible immigration reform and that people who are alarmed today will become more tolerant”.

SGP: “Purtroppo, it is all too obvious that Italian Americans don’t know – or have forgotten – their own history as the descendants of immigrants. We could point out – word-for-word – that what some Italian Americans say today about recent immigrants, was said about It-Ams years ago. “They are dirty. They are criminals. They are dangerous. They refuse to speak the language. They only take advantage of the system. They will never become ‘real’ Americans.” These Italian Americans are oblivious to the irony. As Fred Gardaphé has said, Italian American suffer from an “irony deficiency.” If, in 1906, who had said to an American that in 100 years (2006), there would be two Italian-Americans on the Supreme Court (Scalia and Alito), most people would have thought you were crazy. Yet It-Ams struggled and prospered. So why not give new immigrants the same opportunity? I see the fight over Columbus Day in this context: the old guard which is so invested in the holiday that it can’t imagine any other way of celebrating Italian American history is similar to the Trump supporters who don’t want to imagine a different kind of America”.

In conclusion: for all of these years, Italians in Italy and Italians in America have not “recognized” each other as brothers and sisters; in other words, it seems as though they have never understood each other, and instead have often barely tolerated each other. Now, your book is an invaluable and rigorous study of what has been the Italian American experience over the course of 4 centuries in America. Will it only be used towards academic study, or does it also perhaps have an ambitious objective of finally revealing the Italian Americans to the Italians, and transforming the relationship between these people divided by an ocean?

WJC: “One of our authors, the late Robert Viscusi, describes in an elegant way the combination of longing, anxiety, timidity and fear with which Italian Americans look at Italy. They think of Italy the way orphans think of distant relatives. They know they are related, but they don’t know how they’ll be accepted and indeed they have often been rejected in the past. Their parents and grandparents left Italy willingly—and Italy was fine with their leaving. Now that it has been published in the Italian language for an Italian readership, with its rich illustrations and its compelling narratives, the book can become a formal way to introduce these orphans to their long-lost cousins. It may even result in some adoptions.

SGP: “The book aspires to appeal to academics as well as the general public. There should not be a “ghetto” of Italian American studies just for scholars and another for the public. For more than a century, many Italian academics did not think Italian Americans worthy of scholarly attention. We were the “cugini cafoni dal Mezzogiorno” who left the patria and should just be forgotten. But the work of our colleagues and contributors in Italy, Simone Cinotto, Maria Susanna Garroni, Stefano Luconi, Antonio Nicaso, Rosemary Serra, Maddalena Tirabassi, Edoardo Tortarolo, and the late Francesco Durante (and his magisterial two-volume magnum opus Italoamericana), has changed the way Italians see and understand Italian Americans. Just as Italian Americans cannot understand their history without knowing Italian history, Italians cannot really know their history without understanding the history of migration. We hope the book inspires another generation of scholars and readers”.

Two more questions that we were not able to include in the interview on video: did an Italian identity already exist among the masses of immigrants that arrived in the US from the mainland and the islands? Did they identify with, and feel themselves to be Italian? Or was it– as it still was up until a few years ago in Boston’s North End — more a case of identifying with their regions: as Apulians, Sicilians, Campanians or Calabresi? In other words, is it possible that they have had trouble identifying as ‘Italians’ because this identity solidified in Italy many years after they themselves had left their homeland?

WJC. “Certainly that’s a major issue. There were many immigrants who considered themselves campani or calabresi rather than italiani. For these people, “Italian” was a label that was imposed on them by the United States. Everyone knows how, after Unification, Massimo D’Azeglio said “We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians”. For many of these immigrants to America, who retained their local sentiments and ties, it was not the Italian national government but the United States that “made” them Italian”.

SGP: “I’ll play devil’s advocate and say that perhaps it’s not a bad thing that Italian Americans were slow to embrace an identity as either “Italian” or “American.” And even in Italy, maybe the resistance to a singular national identity is not to be lamented. For all the political propaganda since the Risorgimento, the nation state has not fulfilled its purpose or obligations. There’s no better proof that as soon as it became possible, millions of Italians left the patria. That’s an indictment against the the formation and development of Italy. Today, it can’t be said that most Italians are satisfied with the country. And maybe it was a good thing that Italian Americans resisted the demand by the king or Mussolini that they consider themselves “Italians” first and then calabresi or napoletani or siciliani. This would be a cultural loss in both Italy and America”.

And finally, I’d like to hear your thoughts on another aspect of your volume: that is, how did Italians influence, through their thoughts and actions, the ‘American experiment’ at its origin. I’m thinking of Mazzini, for example, when he wrote, “in the name of the people, for the people and by the people…”

WJC: “So you are saying that Mazzini’s phrase influenced Abraham Lincoln, “of the people, for the people and by the people”. There have always been prominent Americas who paid attention to intelligent Italian writers like Beccaria and Mazzini. Frequently mentioned, for instance, is Thomas Jefferson’s neighbor, Filippo Mazzei, who is said to have formulated the expression, “All men are created equal,” that then found its way into Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence. Here I have to say that I prefer to make an argument I believe is original with me and very much controcorrente. If you read the American Founding Fathers carefully for their references to Italian history, what stands out again and again is the way they studied the details of the failures of the Italian republics of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, governments that one after the other succumbed to tyrants. They read about Siena, Milan, Florence, Padua and many other cities. They thought the republics of Venice and Genoa were despotic oligarchies. They studied Machiavelli’s Florentine Histories even more carefully than The Prince and the Discourses. They even read the Latin and volgare chronicles published by Muratori in the Rerum Italicarum Scriptores. I think the most important Italian contribution to the American project lay in this series of negative examples that showed them how republics can fail. Having said that, let’s hope today’s republics, both Italy and the United States, still have much life in them….”

SGP: “I find Bill’s interpretation both fascinating and convincing. The little I know about the early history of the United States seems to confirm this. In contrast to the common and simplistic reading of American history, I sense that the Founding Fathers were more sensitive to the ironies and tragic sense of history; a sense of history more Greco-Roman than Anglo-Saxon. One thing they surely learned from Italian history is how precarious freedom can be”.

William J. Connell is an Andrew Carnegie Fellow. At Seton Hall University he is Professor of History and holds the La Motta Endowed Chair in Italian Studies, and he was Founding Director of the Alberto Italian Studies Institute. His books include Machiavelli nel Rinascimento italiano; Sacrilege and Redemption in Renaissance Florence (co-auth. Giles Constable); Anti-Italianism: Essays on a Prejudice (co-ed. Fred Gardaphé); La città dei crucci: fazioni e clientele in uno stato repubblicano del ‘400; Florentine Tuscany: Structures and Practices of Power (co-ed. Andrea Zorzi); and a widely praised translation of Machiavelli’s Prince.

Stanislao G. Pugliese is professor of European history and the Queensboro Unico Distinguished Professor of Italian and Italian American Studies at Hofstra University. He is the author, editor or translator of fifteen books, including Bitter Spring: A Life of Ignazio Silone. He is the editor of Carlo Levi’s Fear of Freedom and the first English translation of Claudio Pavone’s landmark work A Civil War: A History of the Italian Resistance. With Brenda Elsey, he is co-editor of Football and the Boundaries of History: Critical Studies in Soccer; with Pellegrino D’Acierno he is co-editor of Delirious Naples: A Cultural History of the City of the Sun.