This intimate relationship between language and life is omnipresent in the books of multiple-award-winning author Lakhous (Clash of Civilizations Over an Elevator in Piazza Vittorio, Divorce Islamic Style, Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet), where the Italian language with its large number of dialects and foreign loanwords is not only a vehicle for narration, but also the protagonist and metaphor for many cultural mechanisms.

I asked Lakhous to speak in depth about his ever-evolving relationship with the Italian language in order to gain a dynamic perspective on its role in a global era of lingua francas. Lakhous’ view is especially interesting given that it is inflected through the vantage point of an Italian of Algerian origin. The interview with Lakhous, who has lived in New York City for roughly six months, was undertaken with the thought of offering new ideas for promoting the study of the Italian language, through the experience of a writer who turned this language into a homeland, to echo one of his most memorable observations.

Amara Lakhous talks with some students after his seminar at Montclair State University

Tell us about your encounter with the Italian language from the perspective of a Berber who speaks Arabic and French. In a recent interview filmed at Montclair Statue University, you said that while the languages of your childhood were in a sense automatically available to you, you had to sweat for the Italian language.

I come from a traditional Berber family of Algiers, which has been a double blessing: on the one hand, city life opened me up to languages such as Arabic, which I learned playing in the streets; on the other, my mother, who would never leave the house, kept my Berber alive. French came with school and it was useful in conversing with my cousins who had emigrated to France and would came to Algiers in the summer.

I have been aware that language is an instrument of power since my childhood. Thanks to my multi-lingualism, I would act as an interpreter and mediate among the members of my family: I was considered “special” and treated as an only child…even though I had five sisters and three brothers. My first contact with the Italian language occurred through a beginner’s class at the Italian Cultural Institute of Algiers, which acted as a launching pad for my discovery of Italian literature (Calvino, Sciascia, Moravia) in French translation, and mostly of Italian cinema (from the classics of Neorealism to Commedia all’italiana and Fellini). My move to Italy in 1995 initiated a period of systematic study of the language because I was very motivated. I would read from morning to evening at the National Library of Rome with the dictionary next to me for when I needed it – coming from French made the transition a little easier. But mostly, I would listen and practice with everybody, even though I never picked up the Roman accent…

In the above-mentioned video interview, you said that a new language (Italian, for you) is an ally, a form of protection and even an occasion to be reborn. Can you expand a little further on these powerful and lyrical images? How can these images be useful to young people who speak a lingua franca like English and may not see the value of such an ally?

I often use the metaphor of craftsmanship. Learning a foreign language is equivalent to acquiring a fundamental set of tools for your trade, which is life itself in this case. From a more down-to-earth professional point of view, learning languages has become ever more important in today’s globalized world. The more you know a language, the more you are able to orient yourself quickly in foreign contexts, and the more languages you know, the more allies you have, and consequently you live better. Right now for me, it’s the turn of English but soon I would like to learn Spanish or perhaps Japanese. True, for those who look at the world from the perspective of American culture, being a native speaker of English is like being “in an iron barrel” [Italian for “on sure ground”] and one may not feel the need for protection; yet, it is always important to maintain a dynamic and forward-looking vision. Once in Italy, American students will understand that while they continue learning Italian, their own language may allow them to teach, or perhaps work as an au pair. Living with more than one language is a way is to step out of the cage that one’s own language and culture can create if we choose to remain comfortably inside it.

The writer during his lecture at Montclair State University

How have you studied Italian over time and how are you still studying it now? All languages require significant commitment; do you find that the Italian language sets up any particular challenges?

When you’re not a native speaker and you speak several languages, you need to stay in close contact with the language you’re studying: in this sense, you’re vulnerable, you can make mistakes. But, vulnerability is an opportunity in the sense that it allows you to ground yourself – mistakes remind you of your imperfections, which themselves are part and parcel of knowing several languages. But, also of the possibility of being corrected which serves as an occasion to improve. There’s no need to feel judged. Learning a language is an act of humility that requires a sense of adventure and determination, like when one learns to drive or swim, especially as an adult. It also provides awareness of the ground covered: knowing that we know, gives us strength, because it turns us into models. That said, one should always learn a language as if it were a game, as if we were children. Besides being a commitment, it should also be a pleasure. This has been my experience with Italian: it is language that I have loved and that has loved me. A language with which I have reached a deep level of intimacy and with which I feel at ease. Challenges? Of course! After all, I’m Italian but not very Italian…

During your talk at Montclair State University, you employed a beautiful expression to underline the fact that your Italian is a language of flesh (lingua di carne) rather than a language of paper (lingua di carta). Can you tell us what you mean exactly with this reference to the flesh and how in reality it intersects with paper? After all, you’re an avid reader of Italian literature…

The language of flesh is that of the people, a language that you hear in the streets and the markets. It is a language worthy of respect and is the language that immigrants often learn. For this reason, I’m against standard tests for competence in Italian that are part of the citizenship process: immigrants speak the language of flesh and it works in their Italian life, yet often they do not pass the test and miss an important opportunity, even though they’re part of Italian society.

The language of paper is that of literature and it is equally important. For me, Sicilian writers have had a fundamental role (Sciascia, Brancati, my friend Consuelo). Sicily itself has played a special role in my Italian experience: during my initial stay in Italy, when as a political refugee I could not go back to Algeria, I found in Mazara del Vallo a familiar place made up of North Africa, but also of Italy, a country I became a citizen of in 2008.

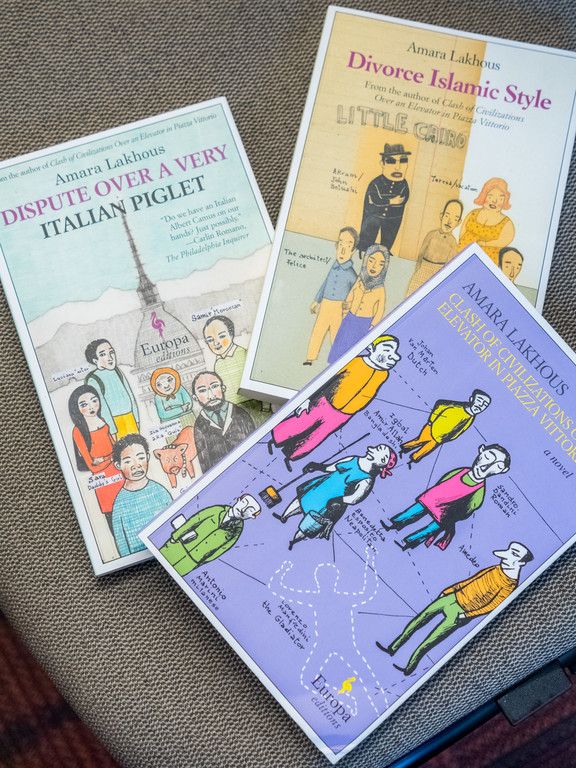

Many of Lakhous’s books are translated in English and published by Europa Editions

On several occasions you have expressed a critical view of the current citizenship law that excludes children of immigrants in Italy, including those born in Italy, and instead opens doors to the descendants of Italian emigrants in the world who may not have retained any active links with the Italian language and culture. How can one go about campaigning for the reform of this law without running the risk of creating forms of essentialism (Identity = Language)?

I know I risk being viewed as a conservative regarding this question, but for me language is a fundamental instrument in terms of being part of a society. This is true for immigrants in Italy and for the descendants of emigrants who wish to acquire citizenship. You cannot be Italian without feeling Italian and you cannot feel Italian without the language.

If you were to come up with a testimonial for the study of Italian, what would be your slogan for young people and also for adults?

Italian is one of the most beautiful languages, especially for its musical quality, and also because it is synonymous with art, culture and genius. It is the vehicle for expressing the creativity and imagination of Italians.

In your books there are many reference to the Italian language. Can you offer us a selection of some of the most incisive images?

In the novel, Clash, the strongest metaphor is the one related to Amedeo/Ahmed who calls the Zingarelli dictionary his milk bottle, and the Italian language his daily bread. In Dispute, I use this analogy between human beings and trees: when deprived of their roots, both die; and I conclude by saying that the strongest root for human beings is language, even if in that specific case I am referring to dialect. But, perhaps this is the metaphor that really captures my relationship with Italian: I consider this language to be like an adoptive mother, it did not bring me to this world, but I am its child.

*Teresa Fiore: Inserra Chair in Italian and Italian American Studies, Montclair State University.