Once again Libya is split in two. There are two rival leaders and the scepter of power is being disputed between the eastern and western regions of the country. The nation that has been in the midst of political chaos for over ten years—after NATO had fought a war authorized by the UN against the Gheddafi regime, is again on the verge of military chaos. Fathi Bashagha was chosen as the new Prime Minister by the parliament in Tobruk while Abdul Hamid Ddeibah, strong because of the support of Tripolitania and of the United Nations that recognized him as leader of the Government of National Accord, is not planning on stepping down. After the elections planned for December 24th failed, the eastern legislative institution invited him to resign from his role as acting prime minister, but Dbeibah said he would only give up his position after free elections were held. The result? Two parallel governments and a situation that puts the resistance of the country at risk. A scenario that takes Libya back a year and that could return the nation to an escalation of violence in the eyes of the international community, which has been too distracted by the Ukrainian crisis. This is proven by the attack on Dbeibah, on the day when Bashagha was being appointed as prime minister. According to the Libyan media, a group of strangers shot the premier’s car, because he is unwanted by the Cyrenaic region. He was able to escape unharmed by the hit men, by climbing into a different vehicle.

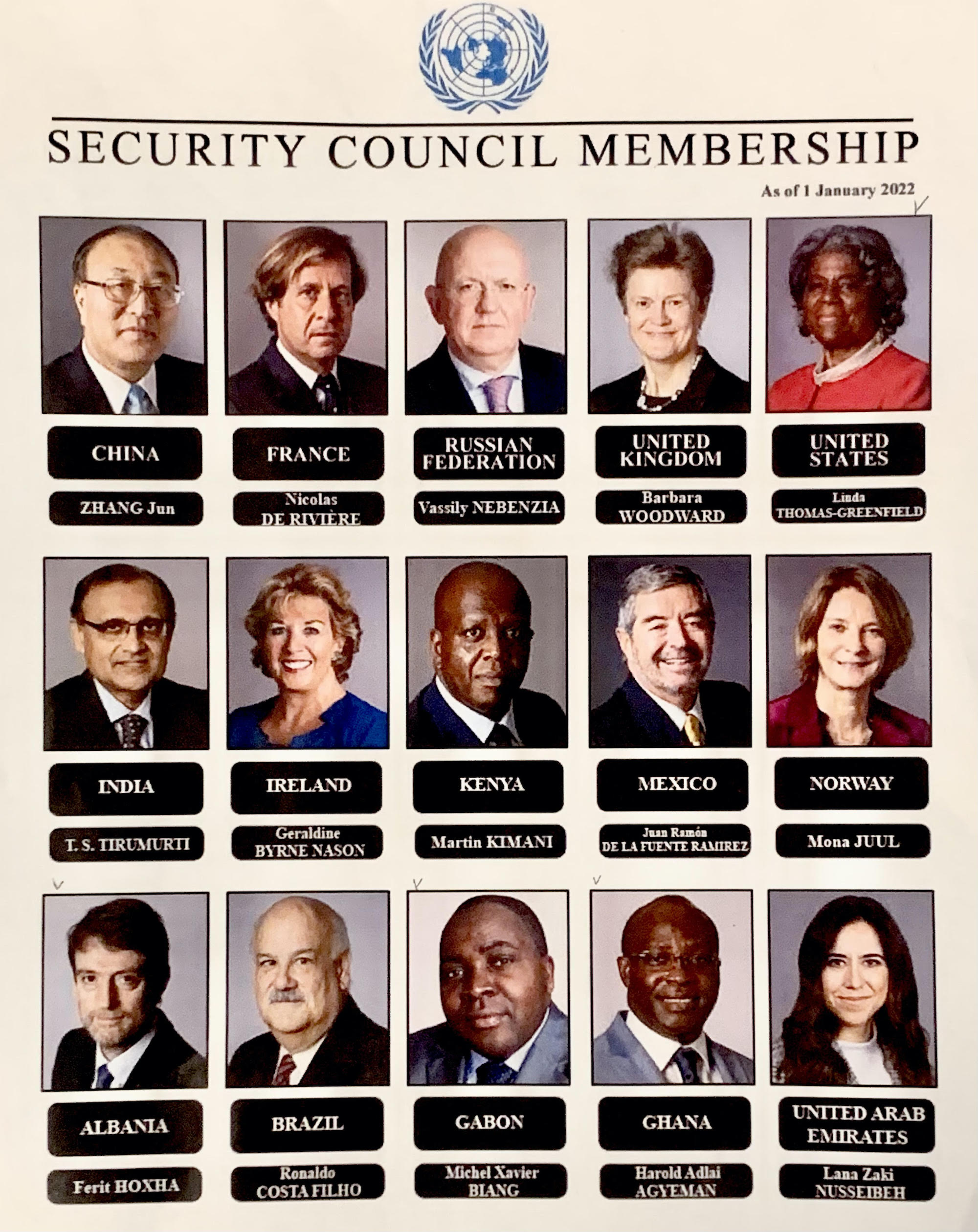

Is the polarization of the country a result of the interaction of the many Libyan tribes that Gheddafi alone was able to hold together? What certainly doesn’t help Libya’s fate is the UN’s Security Council, which is becoming more and more divided. For the second time, the UN’s Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) was not renewed for 12 months, as it is customary: when it expires, it gets a three-month extension, which puts the mission in the vulnerable position of losing funding and having to shut down. The differences among members of the UNSC, particularly the permanent ones, have even prevented choosing the UN special envoy to Libya. After the sudden resignation of Jan Kubis, Antonio Guterres named Stephanie Williams as his special advisor: a linguistic ploy (using advisor instead of envoy) aimed at bypassing the consensus of the fifteen member states. Now, the American diplomat – who has already been the special envoy after Ghassan Salamé left – will represent the highest UN authority in Tripoli. She does not, unfortunately, have the support of all the members of the Council. Russia is already demanding a new person to be named by the Secretary-General before April 30th, when both Williams’ term and her contract as Deputy Chief of UNSMIL are set to expire. The Russian representatives at the UN stated this several times, and the ambassador Vassily Nebenzia reiterated it during a press conference, scheduled because Russia will preside over the council during the month of February.

Although all members, at least in public meetings, have claimed to support free, fair, and inclusive elections, they continue to hold opposing views on who should be appointed as leader of the UNSMIL. This will be an essential figure to instill confidence in the political process and help all Libyan parties to strike a deal going forward. Without the Security Council’s approval, the delicate role of the UN Special envoy loses authority and effectiveness in the mediation process.

It is not easy to understand the differences between the opinions of all fifteen members, based on the notes extracted from their interventions at the UNSC’s meetings that focused on Libya. Answering our questions, Albania, Ireland, and France confirmed that while they recognize the importance of the UNSMIL mission and support the work of special advisor Williams, it is essential to appoint a special envoy who has everybody’s approval. “As recognized by resolution 2619,” Ireland replied, “the appointment of a Special Envoy is very important for the future of the mission.” Albania’s mission exhaustively explained how “it is crucial that the members of the Security Council agree on a candidature equipped with steadfast leadership and committed to the democratic process of Libya and national reconciliation,” choosing a candidate “able to leverage the good offices of UNSMIL.” France, from its seat as a permanent member with veto power, believes that in order to give the mission “all the tools necessary to carry out its mediation, it is essential that the Secretary-General appoint a Special Envoy without delay”. Norway, on the other hand, confirmed full support for “UNSMIL and Special Adviser Williams”.

We are still waiting on comments from other members of the Security Council. According to the opinions they expressed during January’s meetings at the UN headquarters, the United Kingdom and the United States support Williams’ efforts and, the latter in particular, defined the three-month extension for the UNSMIL, during the last UNSC meeting, as “a suboptimal outcome for the Libyan people and a poor result from the Council.” “Deplorable” was Brazil’s comment on the lack of unity shown by the fifteen members. The United Arab Emirates’ position can seem surprising. Often accused of being directly involved in the conflict, supporting General Haftar’s forces with their aviation, the UAE explained during the last UNSC meeting that they would have preferred the mandate to be substantially renovated. Kenya and Gabon also felt similarly, but “African solutions to African problems” is the clear and strong position taken by Gabon who, worried about the deep divisions within the UN institution, expressed her wish for an African diplomat as leader of the UN mission. This proposal was supported by Mexico that, during the January 31st meeting, urged the Secretary-General to appoint an African candidate. Reading between the lines of statements made by giants like China and India, and adumbrated opinion seems to emerge. Both approved a general renewal of the mandate without approving or rejecting Stephanie Williams, although the Chinese delegation thinks it is important to listen to the requests of African states regarding the mission’s leadership. Ghana hasn’t intervened on the subject in recent meetings, nor have they answered our questions.

The Security Council’s impasse is reflected also in the statements made by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. His last announcement regarding what happened in Libya during the past few hours was branded by journalists at the UN headquarters as, at the very least, “confused”. Guterres acknowledged the news although he did not actually take a stand on Bashgha’s appointment as prime minister. He simply reiterated that the country’s stability “is a top priority”, just like the interests of the Libyan people are, since 2.8 million people had registered to vote.

Is there a second name, besides Williams’, that has been circulating among the member states as a possible special envoy to Libya? One that might have been suggested to Guterres during the last few hours, although as of right now he appears to be satisfied with the American diplomat’s work? Authoritative sources coming straight from the Council tell us that, for now, nothing is moving.

And what about Italy? The nation that had staked everything on the government in Tripoli backed by the UN, started to distance itself from both sides when Turkey became its main partner. Italy started to get closer to France because of the intervention of President Sergio Mattarella, who built with the French colleague Emmanuel Macron, an attempt at a joint policy about Libya. Will this work? Leaving Libya–a key country for Italy’s energy supply and for the control of the migration flow–in chaos would be an immeasurable risk. Luigi di Maio, Minister of Foreign Affairs, often said that Libya remains the biggest foreign policy problem for Italy. It isn’t a coincidence that just a few days ago, while Bashagha was appointed by the Tobruk government, the chief Italian diplomat was meeting with Guterres advisor, Stephanie Williams.

Translation by Emma Pistarino