What follows is an excerpt from ‘The Rome Guide’ by Mauro Lucentini, art columnist for La Voce di NewYork. More precisely, is an excerpt from those parts of the book entitled ‘Before Going’, that is which are meant to be read before the actual visit ,while the parts referring to the on-the-spot visit are labeled ‘On the Spot.’ This division is found throughout the book and is unique among guidebooks, being particularly suited to Rome, where it is extremely useful for absorbing the immense amount of information necessary to get an idea of the Eternal City and its 2700 years of history. All the excerpts to be published successively here will also come from the ‘Before Going’ sections. The complete book, including the essential ‘On the Spot’ portions, can be purchased on Amazon. You can read the previous excerpts by clicking here.

Always a famous Roman landmark, and a key stronghold of papal defence, the Castel Sant’ Angelo (Castle of the Holy Angel) played a crucial military role as late as the 19th century. Its history, however, long predates both its use as a fortress and the papal dominion.

Hadrian’s mausoleum. The massive structure was first a tomb built by Emperor Hadrian for himself and his successors in the early 2nd century AD. By then, the Mausoleum of Augustus had been filled and Hadrian’s predecessor, Trajan, had been buried under his own memorial column. Hadrian may have designed his own mausoleum. As noted, he was an able and creative architect. The tomb followed traditional Etruscan models, a squat cylinder on a rectangular base, but it is so much bigger that it is tempting to compare it with Egyptian pyramids. Like them, it has a central sepulchral chamber, which contained golden urns holding the ashes of the imperial family (except Hadrian’s own, which were buried near the top, according to a recent theory) and those of Hadrian’s successors, at least until Caracalla in the early 3rd century.

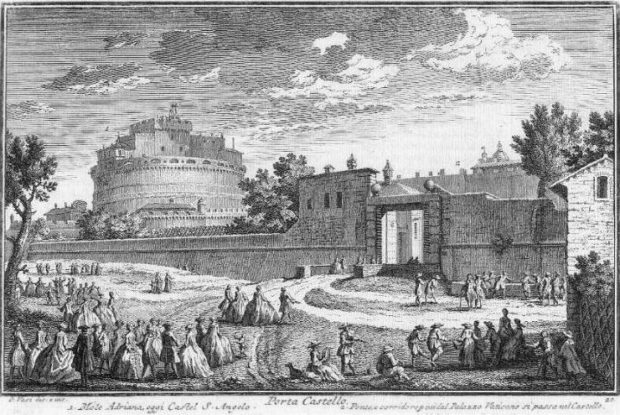

The tomb becomes a fortress. The use of the mausoleum as a fortress dates to imperial times. Its position on the river bank provided convenient defence. Aurelian, the 3rd century emperor who provided Rome with a new set of encircling walls, incorporated the awesome mass into his new defence complex. To protect archers shooting from its top, the monument was crenellated, the first change in its outer appearance. Many more additions and changes followed.

In the 6th century the mausoleum was used to hold back a siege of Goths. The defenders showered the invaders with all the statues on the mausoleum and most of the marble revetment, thus accelerating the change in its external appearance.

The Angel’s sword. The building received its present name and dedication to the Archangel Michael, leader of the forces of God, in the Middle Ages when the popes began using it for defence. An old tradition, recently shown to be legendary, holds that in the 5th century, during a bout of plague, Pope Gregory the Great led a procession of citizens to St. Peter’s to beseech divine aid. Reaching the great tomb-fortress, Gregory had a vision: the Angel of God atop it, replacing a bloody sword in a sheath, showing that the divine fury had abated. The plague then ended and a grateful Gregory gave the edifice its new name. What in reality prompted the change in name, first documented in the 9th century, is unknown.

Throughout the ages, statues of the angel and his sword were placed on the top of the monument, where the statue of Hadrian once stood. The first ones symbolized the military might of the Church. We’ll see an older version with a sword-brandishing angel. The present version simply recalls the legend of merciful intervention during the plague, as the angel sheathes the blade.

In the late Middle Ages, rooms were added over the building for the popes, who often sought refuge there. In the Renaissance the rooms became a full-blown palace.

A mirror of the history of Rome. The long history of the monument as a fortress has mirrored the history of Rome, especially in the Middle Ages, when the city was in the grip of a constant struggle between four powers: the pope, the Roman people, the great feudal lords, and the rulers of the essentially Germanic empire created by Charlemagne. Whoever held the castle controlled the city. Even much later, during Napoleon’s occupations and the fight for Italian independence and unity, the castle was a major strategic-political consideration. Just to make sure, it was not returned to the popes in the Italy-Vatican ‘Conciliazione’ (Reconciliation).

Besides its role in battle, it was a dungeon for prisoners of rank, not unlike the Tower of London. In the 10th century Marozia, a lady of the most powerful family in Rome, managed to have Pope John X imprisoned and strangled in the castle. A couple of years later her son, still in the early twenties, became Pope John XI. Cola di Rienzi fled to the castle in an episode early in his tumultuous career. In the 15th century the last attempt by a Roman faction to wrest the city from the popes before such efforts were revived four centuries later ended with the hanging of its leader, Baron Porcari, from a castle bastion. After this the popes bolstered the fortress even more, transforming its interior and closing its original entrance to create a new, totally controlled access.

Alexander VI Borgia had several victims, including at least one cardinal, strangled, poisoned or starved to death in the castle. Here are some entries from the diary of his master of ceremonies, the unflappable Burchard:

Oct. 28, 1497. Bartolomeo Flores, formerly the Archbishop of Cosenza and private secretary to His Holiness, having been deprived of every honour, rank and benefice and imprisoned in the Castle, was today stripped of all but his shirt … and given a wooden crucifix. He was then transferred from his cell to another called Sammalò … where a bed of wooden planks with a straw mattress, two blankets and a headrest to protect him from the damp coming from the wall had been prepared for him. He received a prayer book, a Bible and a copy of the letters of St. Peter; also, a barrel of water, three round loaves and an oil lamp. The Keeper has been instructed to bring him new provisions two or three times a week. He is to stay there until he dies…

July 23, 1498. The former Archbishop of Cosenza died today in the Castle. It is said he departed with great composure and piety … His body was brought to S. Maria in Traspontina where it was buried with no ceremony. May he rest in peace.

Benvenuto Cellini, a famous Florentine Renaissance sculptor and the greatest goldsmith who ever lived, went to the castle with the fleeing pope during the Sack of Rome in 1527, and manned a cannon. He claimed to have fired the shot that killed the Constable of Bourbon, commander of the invaders; this did not end the siege, however. A rambunctious character, he returned to the castle a few years later as a prisoner, accused of robbing the papal treasury. He escaped by tying strips of bed sheets together, but was recaptured and put in one of the most dismal cells within the castle, which he describes in his wonderfully vivid memoirs. He was eventually pardoned.

Other famous inmates included, 60 years after Cellini, Beatrice Cenci, heroine of one of baroque Rome’s most lurid tales (of whom more later), and in the 18th century the self-styled Count Cagliostro, adventurer, occultist, alchemist and freemason. Arrested in Rome by the Inquisition and held in an apartment of the castle, still known today as ‘La Cagliostra’, he was later moved to an ordinary prison, where he died miserably. Until recently an object of mere curiosity, he is now being belatedly rehabilitated for what appear to have been, in part at least, genuine contributions to the natural and social sciences.

In the 19th century the castle prisons held Roman patriots of the movement to reunite Italy, often destined to execution in the yard below. The most famous of these, though, is fictional: the painter Mario Cavaradossi in the opera Tosca by Puccini. In the last act Cavaradossi is imprisoned and executed in the castle; his lover Tosca follows him to death by leaping off the battlements.

The rediscovery of the castle’s past. While the origin of the castle as Hadrian’s tomb was never forgotten, until not long ago the interior structure of the tomb was hidden by many alterations and the walling up of several sections after the late Middle Ages. In 1823 a papal guard officer lowered himself through a trap door and discovered a long spiral ramp, the original main access. Since then, exploration and restoration have gone on by fits and starts, especially after the union of Rome with the rest of Italy in 1870. Some late-19th- century identifications of parts and details of the building have been disproved by recent research, but are still retained in many books. Thus a vent in the ramp ceiling has long been misidentified as the Sammalò, the worst prison cell in the castle. The famous elevator, built by a castle keeper in 1734, is incorrectly said to have been installed by Pope Leo X more than 200 years earlier, on account of his being so portly. Called sedia matematica or ‘mathematical chair’ by contemporaries, nobody knows today exactly how it worked, whether by human or animal force, or perhaps by water counter-weight. Later it was removed and the shaft walled up for defence, because the opening led to the inner core of the castle.