I gave my heart to the moon, but the moon traded it for a storm.

– A madwoman, Trieste, Italy

Gigi Proietti once said in a cult monologue on YouTube:

“I blew a tire in front of the insane asylum, and the screws fell in a manhole. A crazy guy was looking at me, and he said, ‘Take out a bolt from the other ones and with three in each tire you’ll reach the mechanic.'” Proietti looks at him, incredulous: “So how come they’ve got you locked up in there?”, and the madman replies: “I’m crazy, not a fool!”

According to the data published on May 8th in the Italian newspaper Libero, taken from the Ministry’s latest mental health report, sixteen million Italians suffer from mental disorders, ranging from the minor to the more serious – almost a fourth of the total population. The publication goes on to state that France and Germany invest four times the amount that Italy does. At the same time, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that by 2020, depression – the “Black Dog”, as Winston Churchill called it – will be the second-largest cause of work disabilities, after cardiovascular disease. These are alarming numbers: a decades-long emergency. And it’s a taboo that’s hard to break.

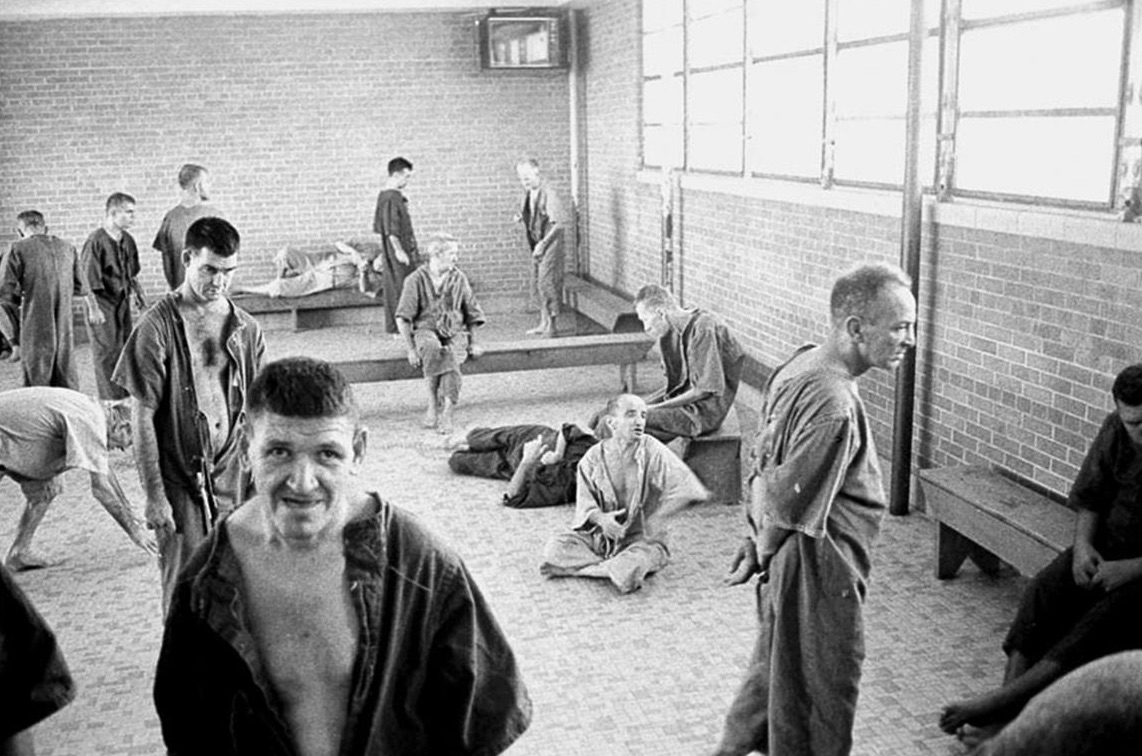

On May 13th, forty years ago, the Basaglia Law was introduced – the Psychiatric Reform Act 180, which mandated the closure of all mental asylums, and, in the hopes of the neurologist that gave it its name, a psychiatric revolution in Italy. The 86 ghettos that were mental institutions closed their doors, finally dismantled. A hundred thousand people became human again. They reacquired their political and civil rights, which had been lost after thirty days of confinement. Giovanna Del Giudice, one of Basaglia’s favourite pupils, referred to the doctors of that period as prison wardens, and the patients as defenseless victims. At last, the walls had fallen between “us and them” – between so-called lunatics and normal people. It was deemed a miracle, and rightly so: we were the only nation to have abolished those concentration camps. It was said that we were pioneers – that we made history. Franco Basaglia acted with honesty, in the best of faith, but those who came after him failed.

I was born fourteen years after the sun set on mental institutions – I was born crazy, bipolar, schizoid, and with several other minor disorders. My parents may not have ever had me locked up in one of those horrendous wards, but in certain moments in my life, the darkest ones, I cursed Basaglia. Was there a future for us mad ones, forced into a limbo since 1978?

Psychiatry in Italy today is still lacking. The mental health wards function, but not sufficiently. The psychiatrists and therapists (there are never enough) are worn out by exhausting shifts: the patients are always too many, problematic, and unmanageable. You must wait weeks, if not months, for a consultation that lasts a mere ten minutes. What alternative is there, then, to the mental institution model, as inhumane as it may be? Basaglia passed away shortly after the law was passed, leaving an immense void. Involuntary mental health treatment, that is, “sectioning”, is rarely ordered. Mauro Guerra died as a result of this. It seems that bipolar disorder sufferers number about a million in Italy, though it’s difficult to say, as diagnoses are often made late and can be incomplete. The emergency room is not our friend. We hinder the treatment of real emergencies with our anxiety, we are not quickly curable; bandages or an injection are not enough. We are often pushed back in bad ways – it has happened to me countless times. Now I smile when I think about it, as I’m beginning to feel better, but in my years of hypochondria, those crazy and desperate races to the ward were the order of the day, and would typically finish tragically. “You are hysterical, go away!” the emergency doctor yelled at me one Saturday afternoon. I had been vomiting for day, and my psyche was refusing any food. I remembering returning home in a daze, just in time to run to the bathroom, while Ternana played. Why did no one understand me?

The very delicate theme of mental illness has long fascinated film directors, from Fellini (Titta Benzi’s uncle yelling “I want a woman!” from atop a tree in Amarcord, or Valeska Gert moaning bizarrely in Juliet of the Spirits) to Von Trier, while even in the last 20 years in Italy the topic has been confronted with courage on the big screen, such as by Virzì in Like Crazy, Pupi Avati in Giovanna’s Father, or Francesca Archibugi in The Great Pumpkin. In literature, the theme of mental health is ubiquitous – Philip Roth’s incendiary Merry Levov is my favourite. The same is true of music, where genius always goes hand in hand with wildness and Keith Moon and Vincent Crane were always forgiven everything. In other words, madness is appreciated in art; it is strangely alluring, yet not in everyday life, where it only incapacitates you.

Even the Italian language is against us: the weather in Milan can be “bipolar”, as can the form of a footballer playing inconsistently. Who would say that Renzi has Down’s Syndrome or is autistic? The sky would fall, and public indignation would surpass every record. But to write that a prime minister is bipolar or schizophrenic is entertaining, the bon mot of a Twitter celebrity. I recall how I have cried when reading about people with mental health issues ridiculed on the web. Elliot Rodger, the most hated serial killer since Charles Manson, armed himself with a military-style weapon and shot randomly at people to avenge himself. For what? He was a virgin and thought that the world and women had it in for him. I never found any article that explained what went through his head. Only hate, anger, resentment towards him. But Elliot, as much as his acts are unforgivable, was the first victim of his homicidal fury.

Crazy people are invisible; the “differently disabled”, as I call them. They laugh and joke and sing and cry, hidden away in clinics. They embarrass families and shatter marriages – those of their parents. Friends and relatives don’t understand; they remain perplexed in front of our eccentricities. At a holiday resort, aged seventeen, I left the room with a dress that seemed pretty to me, even innocent. An organiser, embarrassed, told me that it was transparent, and one could see everything – really everything. I was unable to understand the shades between elegance and vulgarity. To this day, just like the color-blind, I force myself in vain to see what I cannot see.

I have no future, because I alternate between mania and depression. Only a month ago, this article would not have been possible. My boss, Stefano, remembers well the emptiness of my days, the lack of inspiration, of willpower, of everything. Certainly, the drugs calm me down, but the price to pay is very high. The switch to my mind is off, and the days pass without leaving a trace. We are vegetables. Subhumans, once more. I stopped taking them, but mania is probably worse than darkness. I made a careless move and I will relapse.

I don’t have any answers, but I have a blog on Facebook that I just created, called Vherapy, where I bare it all – sometimes entirely – no, I’m kidding, but yes, I’m not kidding, even with respect for authority (and if you are an English-speaking reader, that was an Ugo Tognazzi supercazzora!) – and I show mania as it is: unpredictable, fun, irritating. In my dreams, Vherapy is a place where people with mental disorders like us can meet and share our experiences, since we are left to ourselves and often misunderstood.

Mental illness is not curable – we will never fully recover. But something is possible. It’s possible to eat healthy, because we are what we eat, as Peter Gabriel would say. It’s possible to distract oneself with YouTube, with silly videos, without feeling ashamed, in order not to have to take sleeping pills. Warm baths, long walks, a friend’s hug. Little things help.

I gained 35 pounds in four months due to antipsychotics, losing my slender figure. My stomach was bloated, my face black and blue. The lithium almost killed me, poisoning my body – a drug considered very safe that I was not aware I could not tolerate. Up until a few weeks ago, the panic attacks prevented me from even leaving the house. I would stop at the doorstep, then make an about-face and close the door. Exhibitionism, another thorny aspect, almost ruined me. I considered suicide many times. The day I was diagnosed as bipolar, February 4th four years ago, I was supposed to take an exam in sociology, an oral exam. I got dressed, prepared my backpack, got in the car, and started to sob in the back seat. I was a shell, a fantasm, and I didn’t know it. My mother turned the car around and took me to the ward. I never got a degree. I am not a heroine, but I would be lying if I said that over the years I had the moral support that other sick people are given.

I gained 35 pounds in four months due to antipsychotics, losing my slender figure. My stomach was bloated, my face black and blue. The lithium almost killed me, poisoning my body – a drug considered very safe that I was not aware I could not tolerate. Up until a few weeks ago, the panic attacks prevented me from even leaving the house. I would stop at the doorstep, then make an about-face and close the door. Exhibitionism, another thorny aspect, almost ruined me. I considered suicide many times. The day I was diagnosed as bipolar, February 4th four years ago, I was supposed to take an exam in sociology, an oral exam. I got dressed, prepared my backpack, got in the car, and started to sob in the back seat. I was a shell, a fantasm, and I didn’t know it. My mother turned the car around and took me to the ward. I never got a degree. I am not a heroine, but I would be lying if I said that over the years I had the moral support that other sick people are given.

Giorgia Libero, the twenty-something student that succumbed to cancer just two years ago, enjoyed the unconditional esteem of the Venetians, who followed her achievements on social networks and in local newspapers. During that same period of time, my blog on mental illness received a couple of likes when things were going well, often not even a retweet. Why, I would ask myself, does Giorgia have friends, and I don’t? Why am I alone, while she gets so much attention? So many why’s – enough to fill reems of paper. I didn’t hate her; we were the same age, both from Padua, but the disparity of treatment was evident and very painful. I knew, though, what differentiated me from her, what made me unpopular: Giorgia was strong, just as Bebe Vio and Alex Zanardi are – universal symbols of an acceptable sort of diversity. I wasn’t. I was whiny, introverted, withdrawn. But what could I do? I was born this way – it’s written in my genes. Even crazy people need love and patience, and even when they are not beautiful or good or well-behaved. It’s time to act. Enough with the if’s and the but’s. To paraphrase Tommy Walker, Roger Daltrey’s deaf, blind, and mute guru: see us, feel us. Touch us, heal us.

Franco Basaglia gave dignity back to those suffering from mental illness. Now Italy must carry on and complete the endeavor that began 40 years ago in the wake of Chirlane McCray, the wife of New York’s Italian-American mayor and activist for mental health rights. We must talk about it, we must discuss it. The time has come. And to my fellow Italians, each one of you: embrace us and don’t throw us aside. Because a crazy person is always crazy, but when that person is left alone, he does not have any point of reference. The world is swirling. Somebody stop it, somebody stop us.

Two months ago, in a full maniacal phase, I deeply insulted my best friend’s fiancée, and he has not forgiven me since. It was a foolish act, impulsive, and totally me. Marco won’t come back, and she will never want to have anything to do with me again, but this article is for them and for Alvise, who is gone.

Traslation by Emmelina De Feo