In these days of social turmoil in the United States I feel the need to share my experience, in the hope that it will help my Italian friends to better understand what is happening, or at least, I hope it will bring a different perspective to something quite unknown in Italy. For historical reasons in Italy we have never had the opportunity to develop a mature awareness of racial struggles as in the United States. I do not intend in any way to use my voice to replace or interpret that of the Black Lives Matter movement, but I hope it will provide a glimpse into a deeper understanding of a sensitive problem such as the lives of black people in the United States and elsewhere. I think it is a difficult but necessary conversation.

In my academic and professional career, I have had the privilege of studying in the United States twice: as a teenager in Missouri, in a suburban area near Saint Louis (O’Fallon), through an annual AFS/Intercultural exchange program, and ten years later in Washington DC, to study international relations and economics.

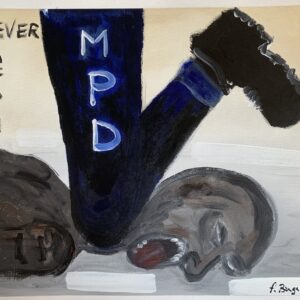

When I returned to the United States in the summer of 2014 to begin my studies in Washington, the debate on institutional racism in the country was rekindled following the killing of Michael Brown by the police in Ferguson (Missouri), a few steps from where I had studied as a teenager. Violent street protests ensued calling for justice on the Brown case, but also making demands for social justice more broadly speaking. I followed the evolution of the protests through my circle of friends from the American high school on Facebook.

Although at 16 years of age that American school had seemed so different and multicultural to me, in retrospect I realized that I had actually lived in a predominantly white neighborhood. Some of my former classmates from that high school had in the meantime become policemen, and were busy in Ferguson during the protests, so I was particularly exposed to the posts of whites, mostly Republicans, who condemned protests and violence and who supported the narrative according to which Brown was a criminal and had pretty much asked for those twelve gunshots.

A few months later, in April 2015, not too far from Washington DC, in Baltimore, the killing of Freddie Gray lit the fuse for another series of violent protests in the area. Protests also followed in Washington DC, in which some of my black friends marched. In particular, on this occasion, the same friends started to become very vocal on social media, in support of the protests. One day, one of them mentioned Malcolm X, of whom I knew only thanks to the “American history” class that I had studied in high school in Missouri ten years earlier. I vaguely remembered that Malcolm X had been the “most violent” and controversial face of the civil rights movement at the time of Martin Luther King.

I did not understand. I did not understand why highly educated people, from the best universities in the United States, people actively engaged in human rights debates, could not only condone the violence of the protests, but had felt the need to express so much anger.

I grew up firmly believing that battles in a democracy should be fought with democratic instruments, with politics, with debates, with elections, with votes, with laws – and I still hold that idea. In any case, I felt the need to discuss it, to understand. They are friends whom I greatly respect and if they felt this need, I was sure that their words and anger could only be well motivated.

Timidly, I knocked on the door of one of them and dared to ask: “why this support?” She replied with the patience of those who want to be understood and with the suffering of those who have fought silently for a lifetime and are tired of fighting, of explaining themselves, of telling their story. You could see this from her downcast eyes and a closed posture (not her usual character), and I could tell from her voice that was trying to keep hold of herself.

She sighed deeply, and exhaled, “I’m tired. We have done this for years, and yet we are still here demanding the same things.” She went on to share with me her experiences and those of her loved ones with racism in the United States, her country. For the first time, I heard the narrative of the struggle for civil rights in the United States from the side of the oppressed. It hit me all at once and opened me to a new narrative, as well as it gave me a deep sense of unease for not having collected the right information before forming my own opinion.

The fundamental point was this: nobody wants to resort to violence to assert their rights. Nobody should have to resort to violence in order for their humanity to be recognized. But when in the course of one’s life, every other possible means has been explored, patiently and constantly, if the only way to make one’s cry heard is to protest with force, then force it must be.

Nobody wants to condone gratuitous violence, but where the violence of a system is exercised daily on a specific target of the population, violence seems to be the only means left available to the oppressed themselves. As early as 1967 (53 years ago) Martin Luther King, in reiterating his commitment to nonviolent struggle, did not fail to note:

“a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice equality and humanity.”

Focusing the conversation on the violence of the protests, or worse, labeling the violence as purely criminal, opportunistic, meaningless acts, means failing to understand what is happening and silencing those who are asking to be heard.

It means not being able to discuss with some level of intellectual honesty the deep roots that led to this exasperation. Ultimately, it means never breaking the cycle of violence, if we don’t tackle first the systemic violence which prompts a response of street violence.

Over the years, thanks also to the coordinated action of the “Black Lives Matter” movement, many awareness campaigns have followed and there have been various episodes of peaceful protests, particularly in the world of sports and entertainment. In 2014, Kobe Bryant wore a “I can’t breathe” T-shirt in protest over the death of Eric Garner at the hands of another police officer. In August 2016, some American athletes began protesting against police brutality and racism by kneeling on one leg during the American national anthem. The case of Colin Kaepernick, quarterback of the San Francisco 49’ers football team, who before a friendly match in preparation for the championship remained seated during the American national anthem as a form of protest, is emblematic. Public opinion accused them of anti-patriotism, of disrespect for the American flag and that these protests were out of place. US President Donald Trump said that NFL owners should “fire” players who protest the national anthem. In 2016, the cast of “Hamilton”, a successful Broadway musical about colonial rebels shaping the future of a new country, publicly appealed to American Vice-President Mike Pence, who was among the spectators, at the end of the show that evening:

“We, sir – we – are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights. We truly hope that this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us.”

On this occasion too President Trump and part of the public considered this display out of place.

These latest protests are not simply the result of the umpteenth, unjustified death of an American citizen, George Floyd – and they are for the most part peaceful protests. They are the result of years of oppression. The video showing the policeman brutally kneeling on Mr. Floyd’s neck, while suffocating him, was once again the straw that broke the camel’s back.

The video rightly provoked the outrage of those who until now had had the privilege of not seeing these injustices before. There has been greater mobility than in the past, also the result of the constant work of organizations and movements for social justice, as well as the skillful use of social media. But it has also provoked the anger of those who, for years, for generations, have been asking for equal treatment.

It has provoked the anger of those who continue to be treated with condescension when appealing for solidarity: there never seems to be a suitable place, or a correct way for their requests to be presented, listened to and addressed. Only a lot of patronizing from those who follow it from a position of strength. This time their cry for help seems to find an echo even outside the United States, but it risks being misinterpreted, at best, or exploited at worst.

In Italy, where we have never dealt with our own colonial past and where for a long time we had a relatively homogeneous population, only in recent years we have started to experience a more visible multiculturalism and diversity that can be remotely comparable to the diversity that is the linchpin of American society. The latest protests can first of all become an important moment to inform us, read and listen to other stories that deviate from the dominant narrative of the white United States.

I want to conclude by offering four lessons that I have learned, in spite of myself, about how you can be allies of the movement of black Americans:

- Inquire and study. It is not every black person’s job to educate you about their condition. I understand that it may seem contradictory to the idea of having a conversation, but in the digital age, there is no shortage of information, there is a lot of material mainly in English: you will find Ted Talks, documentaries on Netflix and much more. Be curious and in doing so be ready to feel uncomfortable with yourself in realizing also the advantages you have been able to enjoy by virtue of simply being part of the dominant community out of sheer luck, thanks to the color of your skin. It is important to get informed and understand our role before trying to start any conversation that can be in any way productive. Like my friend, many black people are tired of fighting, explaining themselves, telling their story. Some will be willing to face the conversation, some will do it with less patience than others. But some are exhausted from speaking on behalf of a generation, and from carrying a burden that none of them had ever asked for. They are exhausted from having to continuously explain their personal stories, of parents, grandparents, etc. They are also exhausted from having to repeat the statistical data that black people are the most vulnerable group to the injustices of the American judicial system. And in general, it is not for them in the first instance to have to compensate for an educational system that fails to include their story in the main narrative.

- Listen to the voice of the unheard, or the concept of “whitesplaining”: it happens when a white person tells a black person how to respond or view a topic, usually when talking about racial relationships or inequalities. Black people are able to formulate their needs and aspirations consciously and based on their own experiences. And they are just as valid as yours. You are not the protagonist of this fight. You are an ally. If you are white, in a predominantly white country, your voice has not only always been listened to, but has been the main narrative voice in the history of your community. Make room for other voices.

- Become an echo chamber, not an interpreter. If you are not black, it is not your job to reinterpret the experience of those who are. It is not your job to speak in their name. The risk of speaking from a privileged position is that of “appropriating” their story, their narrative. The risk is that, despite the best of intentions, it results in removing their voice once again. Your story is already the predominant one. Use your platforms to echo their requests and to give them space for a comparison between their experiences and to be able to mature their requests and their strategies. Let them tell you how you can help their cause.

- It is offensive to say that “all men are created equal” or “all lives matter” when discussing systemic injustice based on skin color discrimination. No matter how well-intended, when someone (often white) claims to “not see color”, they are engaging in a “color-blind” rhetoric which is harmful to black communities for at least three reasons: (1) They deny their own ” whiteness “and all the social privileges and power they derive from it; (2) they deny the “darkness” of other people and all the social discrimination that often results from it; and, above all, (3) they are conceiving racism as individual and intentional, rather than institutional.

Racism in the United States is structural, historical and enduring. The answer cannot be individual, but necessarily communitarian and structural. The modalities of the protests will depend on their oppressors and their ability to know how to listen to the unheard.