In Greek mythology, Lynceus, one of the Argonauts, was gifted with such a penetrating view to see beyond the walls. We might find his contemporary equivalent in Superman, among whose many powers is ‘X- ray vision’. Going back in time, at the at the turning point between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Camillo Olivetti (1868-1943) and Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937), thanks to their foresight, weave so innovative webs as to deeply affect the lifestyles of millions of people.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the very young Camillo Olivetti attended Stanford University and then ‘stood on the shoulders’ of the giants of science and industry of that time. In so doing he was able to keep his vision fixed on distant horizons. In 1908, he founded “Ing. C. Olivetti and C.” in Ivrea, Italy, whose mission was to build a typewriter. Camillo’s entrepreneurial activity continued with the involvement of his son Adriano. Olivetti is a paradigm of the modern industrial design and precursor of the information age.

In pursuing his entrepreneurial plan, the founder of Olivetti was so determined that he accused the Italian bourgeoisie of being dangerously unbalanced on the side of humanistic culture at a time when industrialization was advancing steadily. So wrote Camillo Olivetti in his article on “The spirit of the mechanical industry” published in 1937 by the magazine “Tecnica e Organizzazione”:

“The education of our bourgeoisie has a merely anti-industrial foundation. We are still the sons of the Romans, who left the industrial works to the servants and freedmen and who looked upon them with little regard, so much so that they handed down to us the names of the most mediocre proconsuls, and of the poets and histrions, who enlivened the Roman decadence, but they did not even remind us of the names of those supreme engineers who built the roads, aqueducts and great monuments of the Roman Empire.”

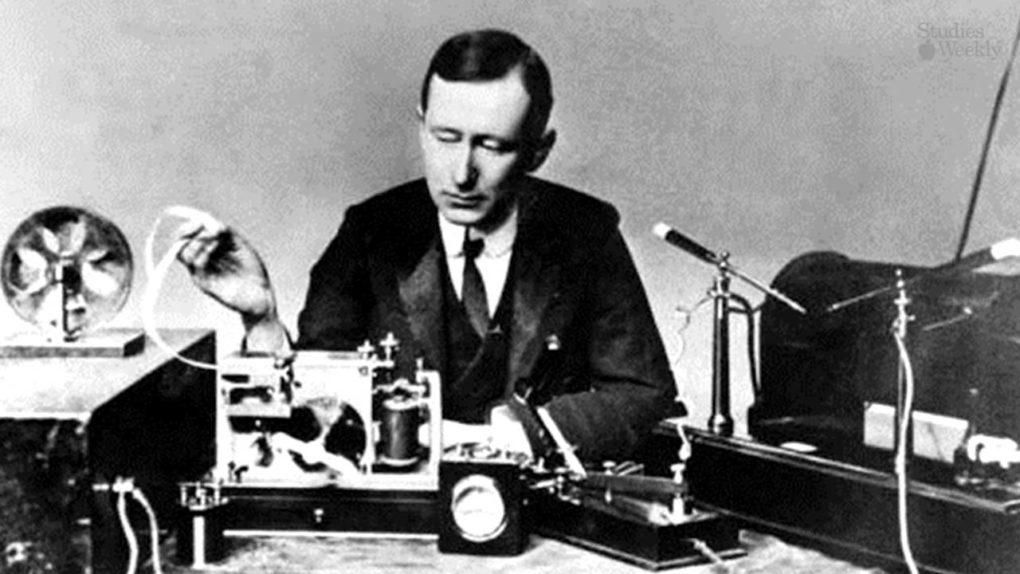

While Henry Ford’s web is heavy, based on terra firma and dedicated to the movement of people and things, Marconi’s is light, airy and used to transport information. His web is spun without thread: it is woven with radio waves that can travel long distances with little to impede their path – not even the curvature of Earth itself. The young Marconi, not confined to academia, engaged in orthodox studies of physics and electromagnetism, but with his sights fixed well beyond the limits of his home near Bologna (the mother was Irish), he avoided the pitfalls of conventional wisdom. For instance, there were those in the 1890s who believed that the earth’s curvature was an insurmountable obstacle to long-distance radio-wave transmission. But Guglielmo was an explorer of terra incognita, proceeding by trial and error. We can imagine him lost in his laboratory activity and receiving no enlightenment or guidance from existing theories. One moment he is busy trying to combine different concepts in an unorthodox manner, the next, he is busy assembling, modifying, changing and substituting different physical components.

Marconi’s web doubles reality, adding the cognitive dimension of mass communication to Ford’s tangible dimension of vehicles and roads. The first radio waves received by Marconi’s equipment in 1895 showed how fragile and small his network was. It was to expand in 1901 when, on the twelfth of December of that year, Marconi was able to link two antennae located on opposite sides of the North Atlantic, in Cornwall and Newfoundland. Since that fateful day a crescendo of signals, voices, words, pictures and images has been captured in the web and then disseminated around the globe. From the dawn of the twentieth century to the late 1990s, from radiotelegraphy and radio communication to the World Wide Web, Internet technologies and mobile phones, the yarn of the web first spun by Marconi has become increasingly taut, thick and strong.

When interviewed by the New York Times 25 years after the experiment he had carried out in December 1901, Guglielmo Marconi said that he wanted the choice of how this network would be used in the future to be left to people’s imagination. A century later, Millennials relegated to second place the pleasure of ‘going it alone’ by car, travelling routes traced by Henry Ford, in favour of ‘sailing together’ in the network conceived by the creativity of Guglielmo Marconi. In cyberspace, in the spaces of shared knowledge, the Millennial generation continues Marconi’s painstaking weaving, placing the right of access to information and knowledge at the top of its value scale and downgrading ownership of a particular means of physical transport. Ford’s network reinforced the value of the exclusive possession of things for safeguarding the interests of the individual, of ‘well-having’. Marconi’s web represents an interlude played between a Fordian scene of the modern age of mass production and the vista that Marconian sound waves revealed to the new age of knowledge, where value is measured by acting together to reach common interests, protecting life itself and ‘well-being’ on, and of, the planet.

For further information, the reader may refer to Piero Formica (piero.formica@gmail.com), Stories of Innovation for the Millennial Generation: The Lynceus Long View, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013