In the United States, a passionate debate – or rather, an endless controversy – has erupted following the tragic events in Charlottesville (VA), where members of the Ku Klux Klan and other racist and neo-Nazi organizations violently protested the removal of a statue of the rebellious General Lee – who, during the American Civil War, fought alongside the southern states, which refused to abolish slavery – from a public garden. The issue at hand is the statues, memorial plaques, and monuments commemorating historical figures that, according to proponents of their removal, have argued political positions or racist and reactionary ideologies offensive to minorities or, more generally, to broad sectors of American society today.

Statues of the leaders of the defeated Confederacy of pro-slavery states aren’t the only ones in danger, for indeed it seems that, at least in New York, the monument most at risk is that of Christopher Columbus. Columbus, the Genovese explorer who was financed by the very Catholic king of Spain, arrived in the New World yet convinced that he had arrived in somewhere else. According to many historical sources, the likes of which are not covered thoroughly in Italian schools, Columbus was not only a courageous and visionary explorer, but also, and above all, a mercenary without scruples for whom the life and dignity of the indigenous peoples found across the ocean were not worth a thing. During the great migration, however, Italian-Americans chose him, Columbus, as their symbol, and thus there is a day celebrating Columbus in many states and cities that celebrate Italian heritage pride with large parades and a myriad of other initiatives.

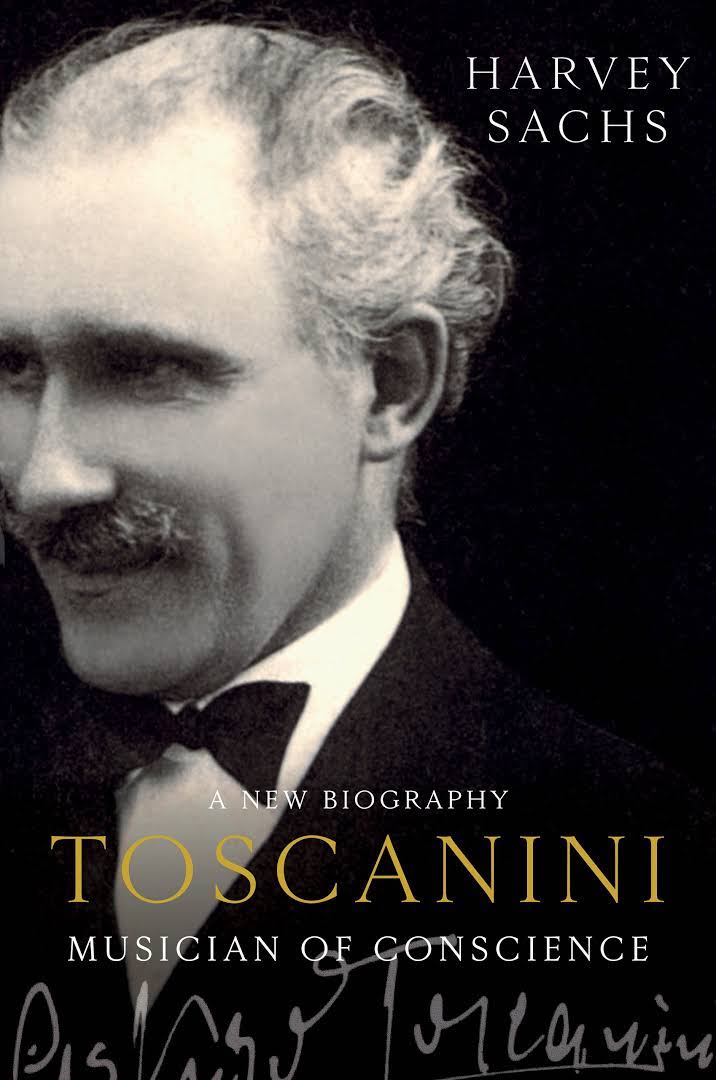

I don’t wish to get involved in the controversy surrounding the possible removal of Columbus’ monuments, nor add my voice to the hundreds that have expressed themselves with great vehemence, and often with little historical knowledge of the issue. I want to instead speak of another great monument to another Italian who spent most of his life in the New World. The monument, in this case, is made of paper: the more than 900 pages of the new biography that music historian Harvey Sachs has dedicated to Arturo Toscanini, defined in the book’s title as the “Musician of Conscience” (W.W. Norton, 2017 ). Sachs had unprecedented access to thousands of letters and documents belonging to the Toscanini family and was also able to listen to more than a hundred tapes, recorded secretly by the Maestro’s children, in which he himself talks to family and friends about episodes and fragments of his long and adventurous life. This definitive volume can therefore claim credit for bringing together the seriousness and comprehensiveness of research through brilliant writing that reads like a gripping novel, and which will likely rekindle the public’s interest in the greatest conductor of the 20th century, and perhaps of all time.

Far from painting the Maestro as a saint, that given Toscanini clear anticlerical and antireligious position would be impossible anyway, Sachs primarily underlines his fundamental contribution to redefining the role of the conductor that, precisely thanks to Toscanini, becomes even in the world of opera, proverbially polemical and on the verge of anarchy, the pivot around which all other figures revolve. In reclaiming his primacy as conductor, Toscanini in reality reclaims the primacy of music as it was written by the composer, free from the arbitrary embellishments, doodles, codas, and pauses that generations of musicians, and in particularly singers, added at will.

But if Toscanini was, without a doubt, imperious and even dictatorial on the podium, in his public life he was one of the most important, and, perhaps, the most famous and feared opponents of totalitarianism and the dictators of his time. He went into self-exile with his family in the U.S. after a group of Blackshirts assaulted him to punish him because he refused to let an orchestra play the Fascist anthem, “Giovinezza,” before a concert in Bologna. Toscanini was a thorn in Mussolini’s side, both politically and personally, since the dictator couldn’t stand the fact that the most famous and celebrated Italian in the world was a fierce antifascist. In 1936, Toscanini journeyed at his own expenses to Palestine to direct the inaugural concert of a new orchestra that brought together many Jewish musicians who were fired and persecuted in Germany and other European countries (not the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra). Mussolini made him hand over his passport on two occasions, but Toscanini never renounced his Italian citizenship, but he only returned to Italy after the fall of the Fascist regime and for two reasons:. to vote for the Republic in the institutional referendum and to direct the concert of the reopening of La Scala in Milan. Of course, I don’t wish to pit the Genovese navigator and the Parmesan musician against each other, but I see in Toscanini a model not only of Italian-ness, but also of loyalty without compromise to the ideals of democracy and liberty that little Arturo had internalized from his father, a volunteer in Garibaldi’s army, ideals that still represent for us the cornerstone of our peaceful coexistence.