The energy in a train station is a strange combination of adrenaline and boredom; waiting to reach a destination while impatiently anticipating to get there. The station is the city’s main artery for all types of travel: trains enter and leave, tourists wander through, travelers and passersby get entangled as in a large piazza… It's treated as more of a 'non-place' in which portraits of countless people and professionals moving through splendid spaces are created. Rome and New York host two significant railroad stations, symbols of prestige and examples that embody the history and architecture of their time.

Though born in different periods and characterized by contrasting architectural styles, the two railroad terminals seem to have navigated through familiar historical currents in their moments of decline as well as their periods of renewal. Knowing this we hope that Termini, which was recently gained notoriety for its inconvenience and physical deterioration, can soon recover and regain the glory that it deserves, akin to Grand Central and its resurgence in the last decade or so.

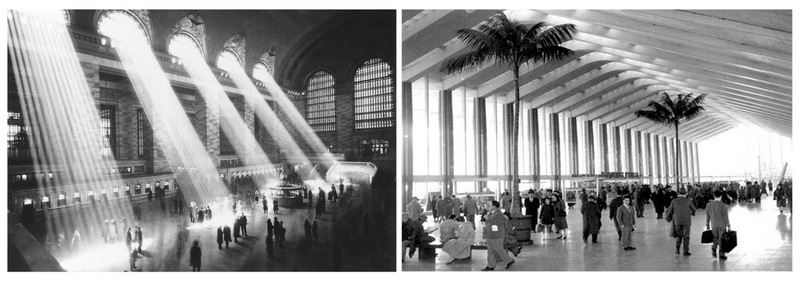

The New York station is a symbol for the great city. Protected and adored, its unique architecture, between its Romanesque ramps, the majestic vault depicting the constellations and 20 meters of arched windows that cascade the sunlight into the imposing Main Concourse, transforms the space into a large stage where the protagonists are the countless travelers. It was Cornelius Vanderbilt who was the first to imagine such a place in the second half of the 19th century. After receiving various proposals, the new Grand Central Station was commissioned to architects Reed and Stem with Warren and Wetmore.

Grand Central Terminal today

Through its very nature and location as a central node of the city, the terminal represented a 'gold mine' of sorts for business: the city block upon which it stands, between 42nd Street and Park Avenue underneath which four subway lines and the most important railway lines of the East Coast cross, undoubtedly one of the most valuable portions of land on earth. In the early fifties however, the station itself was undergoing significant economic struggles, pushing the city to rethink ways to monetize the inherent value of Grand Central.

It was in 1950 that Kodak was granted the possibility of occupying the Eastern bay of the Main Concourse for the purpose of advertising; this is how Colorama was born, an installation like the world had never seen that evolved into a luminous maxi-screen displaying the era's most iconic images to the terminal's 600,000 daily passengers.

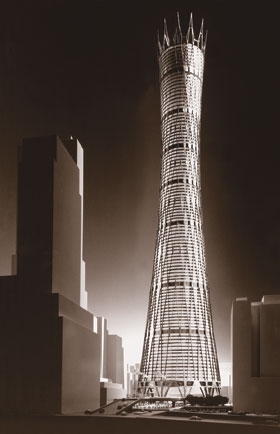

The economic crisis was born from a turning point in the transportation industry. The United States continued to push global boundaries but were no longer doing so through railroad travel, as airplanes and automobiles became more widespread. Throughout the turbulent 20th century, the historical value of the building itself was even put into question leading to the debates in the middle of the century on whether to demolish it entirely and build a new modern skyscraper in its stead. It wasn't long until a sea of proposals from the epoch's most illustrious architects came in. One such proposal illustrated below is from I.M. Pei: a tall and elegant circular mixed-use residential office tower from 1956.

I.M. Pei’s plan for Grand Central Station

A few years later, Marcel Breuer advocated for the construction of a modern tower that integrated the south facade of the existing terminal into its design, resulting in an interesting dialogue with Gropius' much criticized Pan Am building. Breuer's vision quickly stirred violent opposition from the public, even eliciting reactions from Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Philip Johnson amongst others (the latter who stated: "Europe has its cathedrals and we have Grand Central and in Europe, nobody would dream of building a tower over a cathedral"). In the end, Grand Central Station remained intact greatly due to the demolition of another New York staple: Penn Station in 1963, which remains until today an unfortunate scar in the architectural history of the city.

After a long battle, Grand Central was finally declared a landmark building in 1978 where, in contrast to what was occurring in Italy at the time, it was being liberated from any advertising elements that were interfering with its original design (Kodak Colorama was removed in 1990) affirming the architecture as the main protagonist.

In Rome however, showcasing a mix of styles that oscillate between the 30s and 50s, Termini rests upon more than three thousand years of history where we can see the Aggere Serviano, the oldest fortified walls of the city, next to a massive billboard featuring the latest advertising campaign. Like the city itself, Termini developed slowly from different projects, overlapping and often in contrast with many. The structure underwent numerous changes throughout the course of the years, radically changing Salvatore Bianchi's original project from the late 1800s, in which the station was rising like a large foreign object between the fields and vineyards of the Esquilino Hill, a location considered rather peripheral to the city at the time.

Termini Station at the end of the Nineteenth Century

With the emergence of new residential neighborhoods, increased traffic and the World Exposition of '42 approaching, it was no longer an option to delay the modernization of the building- which no longer responded to the needs of the times- even if this meant sacrificing the existing 19th century structure. Ironically for once it seems like roles were reversed: New York was fighting for landmarks while Rome's conservationist attitude was set aside to favor the demolition of the old station, putting functionality over other factors that today would have spared the building. As it stands, Termini station is one of the greatest testaments of what contemporary architecture can offer to a city like Rome.

Thus in 1925 architect Angiolo Mazzoni embarked upon the construction of the new building, an endeavor that was interrupted by the Second World War at which point only two wings had been built: one along via Marsala and the other along via Giolitti, characterized by a succession of travertine arches with impressive brick vaults. In 1947, in a changing political climate, it was decided to complete Mazzoni's project and thus was launched a national competition where the winners (a tie between Montuori and Vitellozzi) would be commissioned to complete the entry with a modern portico and a suggestive atrium. The aesthetic results, in a zone with such archeological interest, pushed the project toward the search of original ideas to reconcile the conflicting conditions, resulting in a project that was renowned at the time for being innovative and out of the ordinary.

Termini Station today

Today, its complete integration in the city, with its various platforms, waiting areas, monuments and shops, reinforce its position within the urban fabric of its surroundings. Constant congestion is a testimony to the vitality of the place, a unique collage that spans from Ancient Rome to the Renaissance, from futurism to post-modernism. The latest works completed for the Holy Year include bars, restaurants and shops where new glass storefronts prevail, as if the transparency of the material would reduce their volumetric impact. Surging trade, with the myriad of glass installations and temporary structures, modified the perceptions of the original spaces, often solidifying the power of the architectural language and contributing to increased confusion and fragmentation: the atrium has been transformed into a labyrinth, scattered with advertising banners that welcome travelers with the same indifference as in any other city, while the construction of a large multi-level parking garage has unfortunately begun above the tracks… Perhaps it's the time to ask ourselves the question: "Would the Americans ever build a parking garage over Grand Central?”.

Traduzione dall'italiano di Christine Djerrahian.