The current crisis has revealed that democracies and non-democracies alike have had differential success in preventing the spread of the virus, in coping with the challenges it poses to their healthcare systems and in addressing the social and economic impacts of the pandemic. To increase the resilience of national healthcare systems, policymakers need to strengthen collaboration between public health authorities, research institutions and manufacturers involved in developing vaccines and antiviral drugs. Public health authorities also need to engage with hospitals, doctors and healthcare professionals to organize widespread testing, tracing and effective treatment of infected persons. In addition, public health authorities should rely on community organizations and civil society associations that reach out to citizens and act as intermediaries between state and society. This multilayered interorganizational apparatus is best organized as a network of networks combining cohesion and stability with flexibility to grow and involve new actors with specific expertise on new infectious diseases.

Such networks, in turn, can evolve optimally only in open societies and democratic polities. Under democratic circumstances, citizens experience that their voice matters in the public sphere. They consequently are more likely to trust in government and behave responsibly. A vibrant civil society can convey support or enhance public health policy measures. Civic engagement and dense associational networks also nurture interpersonal trust which translates into more solidarity with vulnerable social groups. All these effects contribute to strengthened networks of societal resilience to the consequences of infectious diseases. IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices (GSoDI), a large data set of democracy indicators, covering 162 states and 44 years, may help measure such dimensions.

At the beginning of the pandemic, some policy analysts assumed that democracies would have performed better than autocracies in coping with the crisis. It has soon become apparent that state capacities and the quality of leadership played a more important role than the type of political regime. In fact, democracy aspects do not seem to affect fatality rates significantly. International IDEA analyzed whether basic welfare standards, civil society participation and personal integrity rights, for example, are important factors for limiting mortality during the first stages of the pandemic. The conclusion is that democracy aspects do not affect fatality rates significantly if control factors are included in the analysis such as: previous Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) experience; health system capacity; GDP per capita; state control over territory; country size; urbanization; population age; individualist values; world region membership. This means that there are no clear positive or negative effects of democracy aspects on policy outcomes in a sample of 157 countries with a population of over 1 million people in terms of impact on average confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million population and per day since first infection (as of 3 June 2020). However, factors like an effective parliament, absence of corruption, predictable enforcement, and civil liberties significantly affect response speed (measured as days between first confirmed infection and first containment measure) and stringency government response policies. Both democracies and autocracies show slower response times and less stringency, whereas hybrid democracies are associated with high speed and stringency of government responses.

Equally if not even more important than the question of the impact of the pandemic on governance processes and institutions, is how governance practices impact crisis response and effects, and what the pandemic reveals about the quality of governance prior to the crisis. In many countries it has exposed the erosion of the social contract between citizens and the State, especially in those cases where democracy failed to deliver inclusive, equitable growth and wellbeing. It has also revealed the importance of agile, effective governance and state capacity, competent leadership, information integrity, and strong oversight. States that have those qualities have fared better than those that don’t have them or where public trust in governing institutions is being eroded. This means that pandemic responses have varied widely reflecting the underlying capacity, transparency, and strength of the social contract between citizens and the State, which also vary so widely across the different types of political regimes.

Building on its Global State of Democracy Indices and Report, International IDEA developed a Global Monitor of COVID-19’s Impact on Democracy and Human Rights co-funded by the European Union. The Global Monitor will be launched on 7 July 2020. Its objective is to monitor the democracy and human rights implications of measures adopted by governments around the world in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, specifically in the countries included in International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices.

The Global Monitor will be an online platform aimed to be a user-friendly tool for policymakers, civil society organizations, journalists and the public in general to easily access in one place all democracy and human rights-related information on COVID-19 measures, by country, by region and globally. The online platform will provide access to analysis and data produced both by International IDEA as well as other organizations around the world. The information will be provided by country and updated twice a month, with monthly regional summaries.

The monitor builds upon and connects to several other initiatives in which IDEA participates. The Call to Defend Democracy has highlighted the importance of adhering to democratic principles and be mindful of potentially harmful developments of the COVID response to democracy, which the monitor will help track and identify. The Global Monitor also includes links to IDEA’s Inter Pares tracker on COVID and parliament function, which is also funded by the European Union, as well as other papers, analyses, and case studies related to COVID and elections, money and politics, political participation, and constitutional integrity.

The Global Monitor will assess such impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on democracy and human rights, as the declaration of a state of emergency, the postponement of elections, and consequences for civil liberties, media and freedom of expression. A preliminary overview of the situation shows that 60% of democracies have declared states of emergency, as opposed to 36% of hybrid regimes and 13% of autocracies (only four countries). In general, countries have followed constitutional provisions to impose and renew states of emergency.

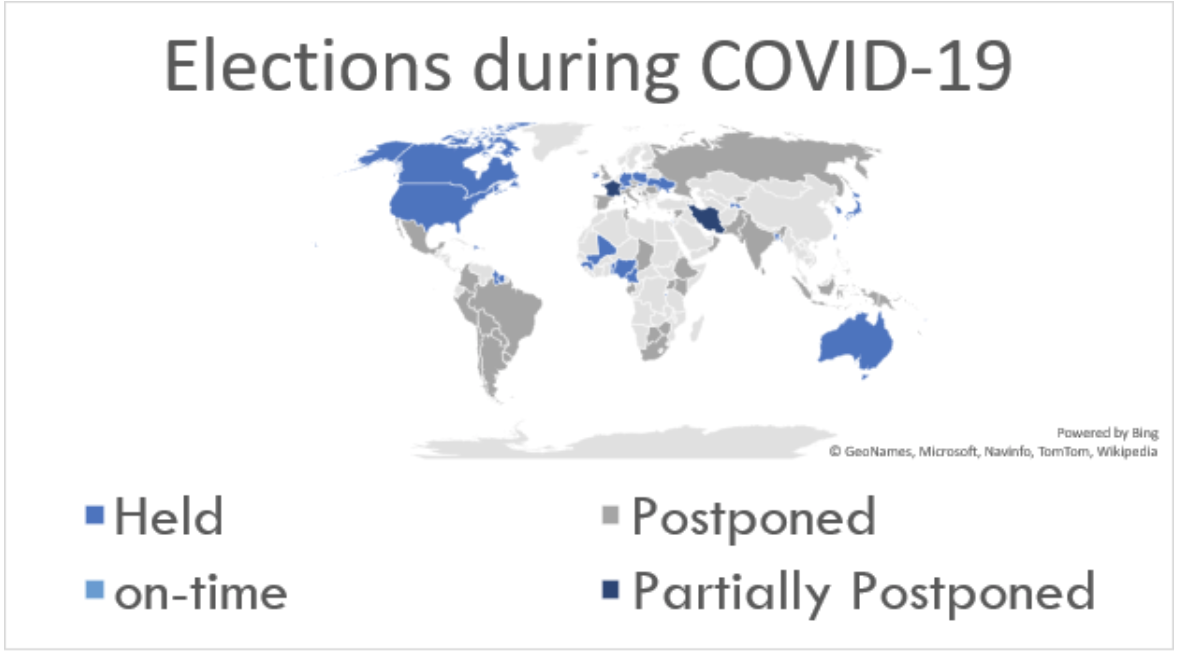

Electoral processes were affected by COVID-19 in 117 countries. These elections range from primary elections (e.g. US), to local elections (e.g. Paraguay), and national-level elections (Israel, South Korea, Guinea, Sri Lanka, Mongolia). About 66% of countries have postponed elections, and 34% have held elections during the pandemic. Some governments resisted calls for postponement, failing to secure political consensus, often to the benefit of incumbent. In Serbia, for example, elections were boycotted by opposition and the ruling party secured 80% of vote. In Guinea elections and constitutional referendum were held in March, and a state of emergency was imposed five days after the election results, banning protests. The country experienced widespread violence. In Burundi, calls for postponement were ignored. Neither health precautionary measures were taken during the electoral campaign, nor international observers were allowed. The election resulted in a landslide victory for incumbent.

Many parliaments have seen their activities reduced or disrupted. About 27% percent of parliaments have experienced worrying or potentially worrying developments from a democracy and human rights perspective. These include situations like: the parliament not being able to summon the executive (Romania); declaring the state of emergency without convening the parliament (Serbia); declaring a state of emergency for long periods without parliament approval (Sierra Leone); adjourning the parliament sine die (Zambia); dissolving the parliament even though elections had been postponed (Sri Lanka).

As regards civil liberties, all countries have limited freedom of movement and assembly in some form. Governments can take measures restricting civil liberties, without affecting the quality of democracy, if the measures are taken following democratic rules and procedures, and if the measures taken are proportional, needed, time-bound and legal. In most cases, restrictions on movement and assembly have been done proportionally, democratically, temporally, and legally. This is especially true for democracies given the strength of their democratic checks and balances and the effectiveness of their oversight bodies. Some countries have created special exceptions about freedom of religion – like Georgia and Mauritania – to maintain the support of dominant religious groups.

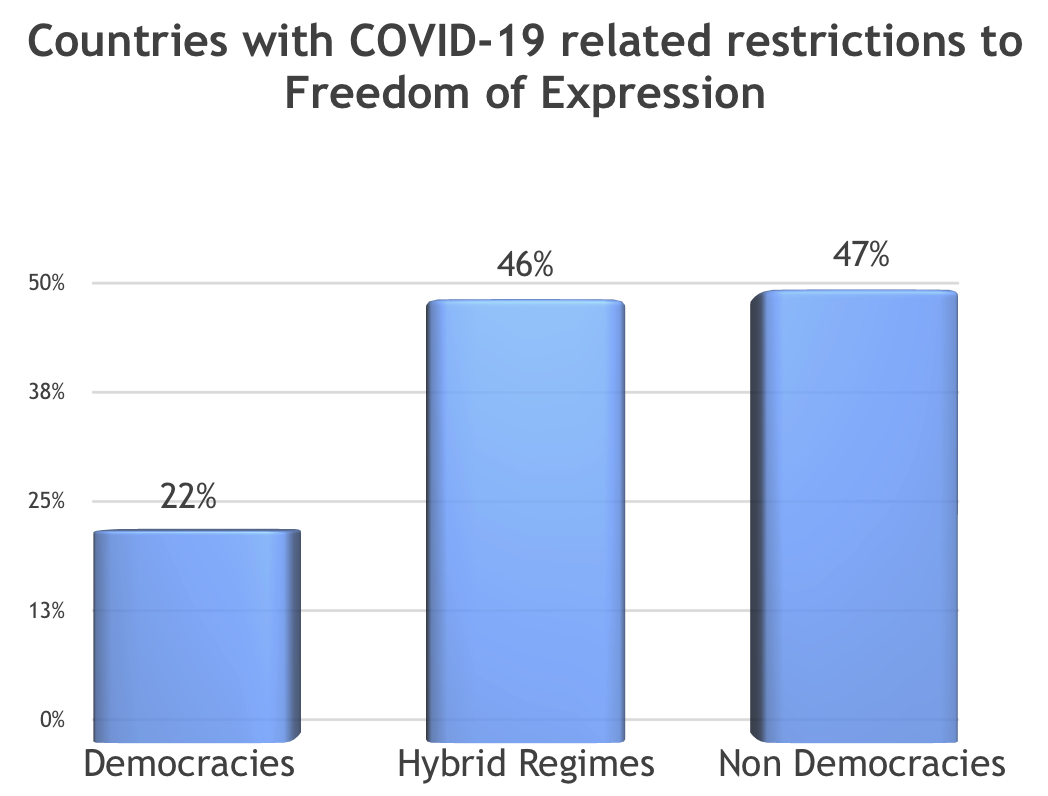

About 30% of the total (49 countries) have imposed measures that reduce freedom of expression. Such restrictions are more common in hybrid and authoritarian regimes. However, also 22% of democracies imposed some restrictions to curb disinformation on COVID-19. Measures reducing freedom of expression are often complemented with attacks on media integrity, present in around 65% of countries, especially in Asia and Africa. In countries like Egypt, Botswana, and India only official governmental statements about the pandemic can be published to avoid the spread of false information. South Africa, Indonesia, and Algeria imposed severe prison sentences to those spreading disinformation.

The economic effects of the pandemic are already extremely worrying and will likely worsen unless effective recovery measures will be undertaken. Already 54% of countries have experienced violent protests related to the measures taken to curb COVID-19 and subsequent impacts on population, as in Niger and Nepal. Also the protests in the USA of the Black Lives Matter movement may be related, in a way, to the COVID-19 crisis, if we consider the heavy toll of the pandemic on the African-American communities and other groups which suffered higher mortality rates compared to the rest of the US population. Several countries have passed legislation to protect the most vulnerable groups, like in Spain and Denmark. With about 70% of the concentration of protests, low- and middle-income countries have been most affected.

Although many countries are still coping with the response to the emergency phase of the crisis, it is possible to underscore some recommendations on the way forward. Countries should invest in building and strengthening state capacities and ensure economic recovery through impartial effective public administration. They should support legislatures, political parties, and election processes to rebuild the social contract between citizens and the State. They should bolster trust by protecting space for public participation, especially by the most vulnerable and excluded groups, and build resilient and durable communities. They should ensure oversight and judicial independence to protect and enhance democratic decision making in the recovery. And they should protect information integrity and media freedom.