What follows is an excerpt from ‘The Rome Guide’ by Mauro Lucentini, art columnist for La Voce di New York. More precisely, is an excerpt from those parts of the book entitled ‘Before Going’, that is which are meant to be read before the actual visit, while the parts referring to the on-the-spot visit are labeled ‘On the Spot.’ This division is found throughout the book and is unique among guidebooks, being particularly suited to Rome, where it is extremely useful for absorbing the immense amount of information necessary to get an idea of the Eternal City and its 2700 years of history. All the excerpts to be published successively here will also come from the ‘Before Going’ sections. The complete book, including the essential ‘On the Spot’ portions, can be purchased on Amazon.

Our walk descends directly to a low-lying area near the Corso on the fringes of the Tiber Bend, lying between the medieval-Renaissance neighborhood near the river and the post-Renaissance settlements.

This has been for centuries the home base of two religious orders, the Jesuits, and the Dominicans, which competed ferociously to be the standard-bearers of the Counter-reformation. There has never been any love lost between them, and the situation is not so different today. Furthermore, the Jesuits, a fiercely independent order, were often suspected of conspiratorial schemes and dictatorial ambitions by all their brethren of a different cassock.

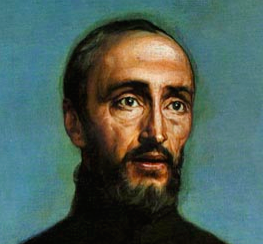

First, we’ll visit the original Jesuit headquarters, consisting of a ‘Church of Jesus’, or Il Gesù, and an adjoining administrative building (to which larger offices where later added elsewhere). The order was founded by a young Spanish nobleman, Iñigo de Loyola (later St. Ignatius) soon after the Protestant upheaval and had a quasi-military character. Drilled into perfect discipline and obedience, it was called a ‘company’ and its head a ‘general’. Its goal was to combat the new heresy, Protestantism, with the weapons of intellect, politics and diplomacy, in a war that could be open or covert as needed. Once papally approved, the order flourished, in part thanks to the support of the many aristocratic families with whom its founder had connections. It gave the church no fewer than six saints in rapid succession: its founder St. Ignatius, his companion St. Francis Xavier, his young disciple St. Aloysius Gonzaga and his followers St. Francis Borgia, St. Robert Bellarmine and St. John Berchmans.

The suspicion of celestial favoritism did not endear the Jesuits to the other orders. They attracted criticism for other reasons, too. Initially, the order followed traditional precepts of priestly austerity, but later, as it slipped increasingly from its founder’s control, it veered toward worldliness and ostentation, reflected artistically in the flamboyant decoration of their churches. But it was their meddling in political and diplomatic affairs that most compromised them, so much so that during the Enlightenment the order was suppressed in several countries, and finally abolished by the pope. With the post-Napoleonic reaction spreading through Europe after 1815, however, those who remembered the Jesuits for their good educational work and for their devotion to dangerous missionary ventures in many parts of the world got the order reinstated.

The church exterior is solemn; the interior was originally intended to be sober, but as the 17th century progressed, a style of architectural, coloristic and ornamental grandiloquence emerged that was meant to smother any possible doubt about the superiority of Roman Catholicism with an onslaught of devotional and æsthetic emotionalism. In this way, art served St. Ignatius’ multifaceted offensive.

In the vicinity is another Jesuit stronghold, the church of S. Ignazio (St. Ignatius), which is built within a great Jesuit academy, the Collegio Romano (Roman College).

Edification and Education. The church was built about half a century after the Gesù, but in the same style; the interior is also somewhat similar, as it was responding to the same pressures of anti-Reformation propaganda. Its fame comes from the tremendous ceiling frescoes by the Jesuit lay brother Andrea Pozzo, especially one that simulates the interior of the dome on a flat surface. The ingenious artist achieved the illusionistic feat after plans to build a real dome were scrapped for lack of funds. Like the Gesù, S. Ignazio has a wealth of sumptuous chapels. One contains the remains of the order’s youngest saint, St. Aloysius Gonzaga, in a precious lapis lazuli urn.

A nobleman like S. Ignazio, indeed the scion of one of Italy’s oldest and most illustrious families, Aloysius renounced his property and title of marquis at the age of 17 to be a simple soldier in the Company of Jesus. He lived in two rooms of the building that encloses the church, and died at 24 while helping plague victims. He was so handsome, it is said that every girl in Rome was secretly in love with him and wept at his demise. His rooms may be reached through the church.

The large building that encloses the church, its solemn façade facing the opposite side, also originally belonged to the Jesuits. It was built in the late 16th century – four decades before the church – as a school, the Collegio Romano, intended to mold the young élite to fill the upper echelons and cadres of the multifaceted Counter-reformation campaign. The Jesuits have always set great store by education and the school was the first of a chain that would include hundreds of schools and universities worldwide, some of them famous, such as Fordham University in New York and Georgetown University in Washington. The Collegio Romano has produced important scientists, scholars, and political and religious leaders, including eight popes. When the Italian state annexed Rome in 1870, it took over the school. For a few decades, it continued to maintain the highest standards, boasting famous teachers, such as the great poet Carducci, and famous alumni. It then declined and is now an ordinary high school.

Piety and Pain. One way in which the Dominicans and Jesuits competed for primacy was by outdoing each other in pious zeal. A remarkable token of this is to be found in Via del Caravita, a street running from S. Ignazio to the Corso. It is a little Jesuit church, technically an oratory, founded in the 17th century as a base for charitable work, but also used for a renewed, and indeed extraordinary, ritual of penance: self-flagellation. In keeping with their astute and pragmatic spirit, however, the Jesuits did not so much practice this edifying ritual as exhort others to do so. The oratory is not much to see, so you won’t miss much if you find it closed, as it usually is. Yet it is worth remembering for the bizarre ceremony that unfolded there every Friday evening after Mass, until about 1870. A 19th-century traveller, Lord Broughton, described it thus:

The pious whipping is preceded by a short exhortation, during which a bell rings, and strings of knotted whipcord are distributed quietly among the audience. On a second bell the candles are extinguished – a loud voice issues from the altar, which pours forth an exhortation to think of unconfessed, or unrepented, or unforgiven crimes …while the audience strip off their garments, the tone of the preacher is raised more loudly at each word, and he vehemently concludes: ‘Show, then, your penitence – show your sense of Christ’s sacrifice – show it with the whip.’ The scourging begins in the darkness, the tumultuous sound of blows reaches you from every direction while the words ‘Blessed Virgin Mary, pray for us’ burst out at intervals. The flagellation continues fifteen minutes.

Rome’s great 19th-century poet, Gioachino Belli, made fun of these fanatics in his poetry. In one marvellous sonnet, two young lovers, who have just met on the Corso, look for a place to relieve their sudden amorous urges.

I ran to her with open arms: “Oh Ghita! Je curze incontro a braccia uperte: “Oh Ghita!

Wouldn’t it be great?” “But where?” she said … Propio me n’annerebbe fantasia!” Dice: Ma indove?”…

They sneak into the oratory and end up making love in a confessional as soon as the candles are put out for the ritual.