The US presidential election is just over a month away and the eyes of the world are on that fateful moment that has the potential to change the destinies of millions of people far beyond the borders of the United States. The almost unanimous reaction after the first debate on Tuesday was one of great disappointment, if not disgust, at the foul spectacle offered by the two challengers for the most powerful elective office in the world. The responsibility for the disastrous outcome of the debate should not be equally divided between the two candidates. Trump’s absolute disregard for the most basic rules of good manners and his shameless bullying behavior would have dragged Cicero, Savonarola, and Mahatma Ghandi into the gutter of insults, lies, slander and disconnected phrases.

Many of my American friends have wondered if this form of political confrontation still makes sense and if it wouldn’t have been better for Biden to walk away in the middle of the event. Others argue that it would be better to cancel upcoming debates altogether. In truth, for years there have been doubts about the actual usefulness of this very American political tradition that used to make more sense in less polarized times, and when the sources of information were fewer and more reliable. In the era of Twitter, when candidates seem to communicate directly with their electorate without mediation and without filters, the electoral duels that score hits in the form of memorable phrases seem inexorably obsolete.

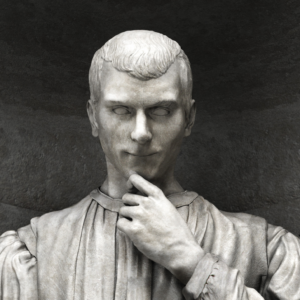

I am teaching a course on Machiavelli in the historical and political context of the Italian Renaissance to about forty New York University students, and I thought it appropriate to suspend my cycle of lessons and instead involve the students in an exercise in democratic dialectics, in the form of the debate. American schools and universities foster a glorious tradition of dialectical education that includes debate teams with tournaments and coaches, as if it were a real sport. It is a training ground for the use of words that teaches students to speak in public, to express their ideas clearly, to listen to the reasons of others, to counter in a firm yet polite manner. All values put into serious crisis by the last presidential debate.

And so, I asked my students to take sides and choose one of the three parties that dominated the Florentine scene at the end of the 15th century: the Palleschi who wanted a formally republican government under the discreet yet strict control of the Medici family, the Piagnoni who supported the regime of almost direct and theocratic democracy of Fra’ Girolamo Savonarola, and the Arrabbiati who demanded the return of the ancient republican institutions under the control of the economic oligarchy.

I invited the students to meet for their party’s convention and to write a short programmatic document on internal, foreign and economic policy. At the end of the conventions we proceeded to the debate during which the representatives of the three parties answered the precise questions asked by me and my colleague, acting as moderators. The students, who were first surprised by the unusual format of the lesson, got carried away and were thrilled by the challenge. They overwhelmed me with their competence and ability. They did not insult or interrupt each other; they did not go off topic, and four of them even changed their minds (and party) during the debate.

For almost two hours we never mentioned Biden or Trump, only Soderini, Machiavelli, Leone X and Savonarola, but it was a great exercise in practical democracy. Educating on the process of democracy is not indoctrination, it is a feasible and exciting undertaking and it is our main duty as educators.