Entering through the side entrance of the New York Botanical Garden (Mosholu Entrance – across from the railroad station), the first work of Kusama‘s that one encounters is a group of trees covered in red cloth and large white polka dots. The cloth wraps around the trunk and some of the branches. The bark disappears, leaving room for the colors and polka dots, which seem to invade the tree, as if to color it all. The artwork is titled “Ascension of Polka Dot on Trees”.

“Polka dots are something of a trademark element in her work since the early days,” explains Paula Capps, teacher of landscape design history at the New York Botanical Garden. ” One of the key things is the repetition. By repeating in patterns and different sizes and covering all surfaces, she can achieve both obliteration of our perception of shape and form, and hallucination or disorientation in terms of understanding where we are in physical space.”

The work that somehow encapsulates all of Kusama though is “Pumpkins Screaming About Love Beyond Infinity” (accessible only with the “KUSAMA Garden & Gallery Pass ticket”). The visitor enters a dark room and is confronted with a cube-shaped glass case measuring one meter by one meter. A few lights illuminate a group of pumpkins of different sizes and different shapes. They are all yellow with black polka dots. The closer you get and look inside the case, the more you are immersed in an endless yellow and black world. You can no longer tell if the pumpkins are on the top, the bottom, or the sides. They are everywhere. And the more you try to look away, the more you see more of them on the horizon. Everywhere. And in that infinity you get lost, with pleasure.

Paula Capps studied garden design history at Oxford University. She has visited and studied gardens in the United States, Asia, and Europe. And for several years she has been teaching the “Landscape Design History” course. What this means is the history of that art form that human beings have used to remind themselves of their relationship with nature. A relationship sometimes of control and sometimes of respect.

We asked her a few questions to better understand the meaning of Kusama’s works and the sense they have today. Below is the full interview.

How do you see Kusama’s art and the New York Botanical Garden working together?

“Kusama’s art takes a number of forms. For example, her more colorful, vibrant artworks are almost a disruptive force in the pastoral, naturalistic landscape that we find at the NYBG. We walk along, perhaps daydreaming, in this calm sanctuary in the midst of a rushing, always in a hurry, city, and suddenly we come to a monumental, brightly colored piece and we are brought up short and reminded that we are also in a place that explodes with color in the spring and summer and fall. It’s a place where thousands of small miracles happen out of sight every day. And it’s as if Kusama has internalized that, and processed it through the filter of her own life experiences, then gifted it back to us, visualized it in a startling new way.”

Which garden or gardens come to mind when you think about Kusama?

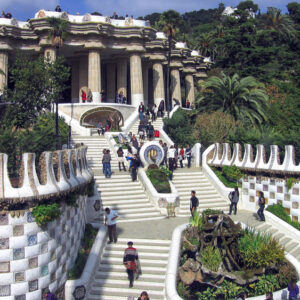

“This is probably no surprise, but the visual vocabulary of Antonio Gaudi’s Park Guell in Barcelona seems quite compatible with Kusama’s. Gaudi, like Kusama, was inspired by nature in all its variety, and his forms are colorful and dynamic. While Park Guell was designed to accommodate nature, and there is a great respect for nature, it is clearly human-made. Likewise, with Kusama, her pumpkins are pumpkins, but no one would think they are actually that humble seed-filled vegetable that hides itself among vines and leaves. One difference I would see is that Gaudi is more optimistic and idealistic, more hopeful, and his energy comes from this. Kusama’s work can sometimes appear more reflective, even troubled, behind the surface brightness.”

Kusama’s life is dotted with flowers and more in general, with nature. She was born in Matsumoto, in the middle of the Japanese Alps. Her father owned a seed nursery. Growing up, she was surrounded by fields of flowers that she has admitted, sometimes felt overwhelming. And then she came to America with the support of Georgia O’Keeffe, an American painter who showcased flowers as the main topic of her works of art. What do you think nature means for Kusama?

“If we go back to that idea of miracles, and of color, and even of the seeds that the hard pumpkin shell protects, then I think we have a way into understanding something of Kusama. Her engagement with patterns and colors I think, comes from her childhood immersion in her family’s seed nursery. Like O’Keeffe, she focuses our attention on a natural form very often, by magnifying it. Visually, where O’Keeffe’s work tended to the abstract, Kusama’s work can be the opposite: highly decorative, and even works that are not decorative tend to be visually complex. My study of Japanese gardens really brought home to me the ancient tradition that man is not separate from nature but is a part and parcel of it. In some senses, I think Kusama is constantly dealing with that: being a part of nature or being an independent self – I think her dialogue with herself and us about being part of infinity, of the cosmos, comes from this conflict.”

Another of Kusama’s main artistic features is the use of polka dots. What’s their meaning in her art?

“Yes, these are something of a trademark element in her work since the early days. One of the key things is the repetition. By repeating in patterns and different sizes and covering all surfaces, she can achieve both obliteration of our perception of shape and form, and hallucination or disorientation in terms of understanding where we are in physical space. For Kusama, much of this applies to obliteration of the self, but viewers bring their own thoughts and histories to create their own experience. I think the three-dimensional dots – her reflective steel spheres – are an elaboration of that idea. When you look at them, you see the same image over and over, but each from a slightly different angle. And you the viewer, are at the center of the image, and the background – whether it is an interior space or an outdoors space – is your frame. So this all goes back to the idea of the self in nature.”

In your opinion, as an American who is also passionate about Japanese traditions and culture, how much of Japan is in Kusama’s works of art? And how much of America?

“One thing that Americans may not be quite so aware of is the pervasive idea of ‘kawaii’ which is roughly translated as ‘cuteness,”’ which is very popular in Japan. It embraces the childlike form and adorable fictional characters, bright and shiny colors. Kusama’s visual expression is very much influenced by kawaii. At the same time, perhaps her self-awareness and tendency toward self-promotion, putting herself out there – comes from that flamboyance of the American art world she was involved in with Warhol and others; in Japan, self-promotion is not really acceptable.”

Telling the story of Kusama is also telling a story of an Asian woman who struggled to be accepted by the mainly male art world of the ’60. Being a young, female, Japanese immigrant limited her opportunities to be hosted in art exhibits. Most insultingly, several of the works she was able to show were copied by prominent white, American male artists like Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg. Do you see that same pattern in the history of landscape design? Are the most celebrated landscape designers mostly men? Are there any women in the history of landscape design that you feel have been neglected?

“Of course, as a landscape historian, I believe gardens are an art form. And as in the art world, the history of gardens is a story told about men, or about gardens that were designed FOR men — and sometimes for their egos, to tell their story in symbolic landscapes tying them to great deeds of the past. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that you have women like Jane Loudon and Gertrude Jekyll and, slightly later, Beatrix Farrand, doing work that was literally groundbreaking. Jekyll especially set out a style that has been popular for 150 years – the English garden style. It’s an interesting topic since we are looking at Kusama’s exhibition in pride of place at the NY Botanical garden, where we can also see the work of three pioneers in American landscape design: Mrs. Farrand, Ellen Biddle Shipman, and Marian Coffman.”

The story of Kusama also tells a lot of the story of New York and its avant-garde spirit, the counterculture, looking ahead to explore new solutions and new points of view. Do you think that spirit still exists?

“Whenever I return to New York after spending time anywhere else, the first thing that strikes me is the energy. We are always looking for new ways to do things here, whether or not in the art world. Kusama at the NYBG and “Hamilton” at the Public Theatre – we are always about the future, about reinventing, about new ways of seeing. We are always looking forward in New York.”

What does looking forward mean for you in New York?

“Our slow emergence from the pandemic during a spring season is especially resonant for me. We’ve been through four seasons during our time of isolation, and I certainly recall doing yard work last summer – and yet in my mind, it has been a pandemic-length winter. I’m looking forward, now, to many kinds of emergence and renewal – reviving the theatre, art exhibits, street life – all the interactions that give New York its creative energy. And this time of year is a reminder that in spite of all our troubles, nature is always there for us – we can plant a seed or a bulb and it will sprout and then bloom or produce fruit, and then go through its life cycle and that will start again. It’s very reassuring.”