28 years ago, Giovanni Falcone, one of Italy’s senior anti-Mafia investigators who had been expected to head a new agency that had been created to combat organized crime, was killed when his armored car was blown up by a massive explosion.

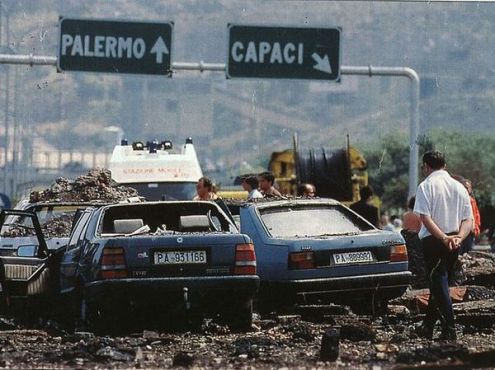

On May 23 1992, magistrate Giovanni Falcone, his wife Francesca Morvillo and three of his bodyguards, Vito Schifano, Rocco Dicillo and Antonino Montinaro, were killed by the Mafia in a massive explosion that blew up the highway A29 Palermo-Punta Raisi, in proximity to the exit of Capaci.

Falcone had landed minutes before at Palermo’s Punta Raisi airport after a trip to Rome and was being driven home in a convoy with two other Fiat Cromas: one driving in front, one following. Approximately 1000 kilograms of TNT were remotely detonated by a mafioso positioned on a hill overlooking the highway.

The attack took place at exactly 17.57 (5.57 PM) on a Saturday afternoon and the news broke shortly afterwards. At the time, I was working as the Rome correspondent for The Independent and The Independent on Sunday. The assignment editor of the latter called me and told me to write a short report for the front page of the paper that was being modified to make room for my piece.

***

The story was titled: “Bombers murder Italy’s leading anti-Mafia judge.”

The mafia struck its gravest blow for a decade against the Italian state yesterday with the assassination of Giovanni Falcone, the prosecutor who sent much of its leadership to jail in 1987.

Falcone, 53, died when a huge bomb blew his car off the road at the exit of a motorway tunnel as he travelled under police escort in Sicily. The bomb, thought to have contained more than 2,000 lbs. of explosive, also killed Falcone’s 36-year-old wife, Francesca Morvillo, and four other people, including three policemen. Twenty people were reported injured.

The death of the man who was the popular hero of the anti-Mafia struggle left Italy in a state of shock. The Prime Minister, Giulio Andreotti, mourned the loss of “a true servant of justice”.

Falcone became famous when he led the legal team behind the 1987 “maxi-trial”, in which 12 of the 13 members of the Mafia’s ruling committee, the cupola, including Michele Greco, the boss of bosses, received life sentences. Although Falcone’s last job was in the prison service, it was rumored that he was about to be named as a head of a new office to take on organized crime.

The attack happened as he was travelling in an armour-plated limousine from the airport of Punta Raisi to his native city, Palermo, where he had insisted on keeping his home despite the security threat. Falcon’s Fiat was second in a four-car convoy. Italian radio said the blast left a scene of utter devastation, with the wreckage of several cars strewn among the rubble.

Falcone was taken, still alive, to a Palermo hospital where doctors were unable to save him. He died at 7.05 pm. Just under an hour after the explosion. His wife died four hours later.

Falcone’s expertise was in tracing crime though banks. His first job as a prosecutor was in bankruptcy cases, then he moved to the team of prosecutors in Palermo responsible for handling Mafia cases. In the late Eighties he led the drive to trace the millions of dollars of profits from the drugs trade that was laundered through international banks.

The result of these painstaking investigations was the maxi-trial of December 1987, which handed down 19 life sentences and 2,065 years in prison to 338 of the 464 defendants. It was not the first Mafia trial, but it was the first time that the Mafia as an organization, stood trial in Italy.

Less than a year later, the anti-Mafia team was broken up. Soon after, in Rome, top investigators warned parliament that the Mafia was in total control of parts of Sicily, Calabria and Campania. The Mafia’s economic power, they said, had made it an alternative power to the state.

In the recent general elections, many of the politicians who had protected the Mafia lost their power. Cosa Nostra apparently decided to strike back before it was too late.

The Mafia has not challenged the Italian state so directly since September 1982, when gunmen murdered Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa, the general just installed as prefect of Palermo with a brief to lead the war on organized crime.

***

On Sunday, I wrote the following obituary that appeared on Monday, May 25 1992, in The Independent.

***

FROM: The Independent (May 25th 1992) ~

By Wolfgang Achtner

Giovanni Falcone, judge, born Palermo 18 May 1939, Director-General of Criminal Affairs Ministry of Justice 1991-92, died Palermo 23 May 1992.

Giovanni Falcone was more than Italy’s top anti-Mafia magistrate. For most Italians he had become a symbol of the state’s battle against Cosa Nostra.

Falcone, blown up by a one-ton bomb on Saturday, was one of the original members of the so-called anti-Mafia ”pool” of magistrates founded in the early 1980s by the then Chief Investigating Magistrate, Rocco Chinnici, himself killed in a Mafia bomb attack in 1983. This small group was responsible for handling all cases dealing with Cosa Nostra and its activities on both sides of the Atlantic, and it was they who traced the millions of dollars of profits from the narcotics trade that were laundered through American and Swiss financial institutions.

In December 1987, the results of their investigations enabled the court of the so-called ”maxi-trial” of the Mafia in Palermo to hand out 19 life sentences and an additional 2,655 years in prison to 338 of the 465 defendants. Twelve of the 13 members of the Cupola or Commission, Cosa Nostra’s command structure, were sentenced to life imprisonment, including Michele ”the Pope” Greco, the alleged ”Boss of Bosses”, who was charged with 78 murders.

The maxi-trial was the first time the Mafia itself was taken to court. The 8,067-page indictment opened with the words, “This is the trial against the Mafia-type organization called Cosa Nostra, a very dangerous criminal organization that, through violence and intimidation, has sowed and still sows death and terror.”

Falcone and his colleagues were also responsible for the arrest of the former Christian Democrat Mayor of Palermo, Vito Ciancimino, and Sicily’s powerful tax collectors the Salvo cousins, who belonged to the ”third level” believed to consist of corrupt politicians who protected their Mafia clients and otherwise unimpeachable businessmen and financiers who benefit from Mafia influence and capital. Falcone himself preferred to speak of a special “closeness”, a ”convergence of interests”, between the mafiosi and the politicians: the mafiosi, he said, controlled the game.

In the past, when each magistrate had been working on his own, to stop an investigation it was sufficient to intimidate or eliminate him. The creation of the pool, the magistrates working together and sharing information, put a stop to that. But there was a price to pay: Falcone and his men had to give up living normal lives, to travel to work in armoured cars, guarded by men with machine-guns, and to operate in a concrete- and steel-reinforced office locked behind thick steel doors.

After the maxi-trial, the Mafia adopted new tactics against the men of the pool. Rumours, picked up by ”friendly” newspapers, suggested that Falcone and his colleagues were trying only to advance their own careers by exaggerating the danger represented by the Mafia. Falcone himself paid dearly. When the position of head of the Palermo pool of investigating magistrates became vacant, he was pushed aside in favour of another, older magistrate, with only a year to go before retirement. Next, the Magistrates’ Superior Council (CSM) in Rome decided he was not a suitable candidate for the position of High Commissioner against the Mafia. Then, when in June 1989 a 50-kilo bomb was discovered outside his summer house, his opponents hinted that he had planted the explosives himself.

When, soon after, Falcone was appointed Director General of Penal Affairs at the Ministry of Justice in Rome, some of his former allies accused him of having sold out to the politicians. When, again, his name was put forward as one of two possible candidates for the job of head of the new “Superprocura”, Italy’s FBI, charged with fighting organised crime, Falcone’s critics suggested he had become a puppet of Claudio Martelli, the Justice Minister. In vain, Falcone reminded them that it was he who had convinced Martelli to create the organization.

”Cosa Nostra always acts like this,” Falcone complained to a colleague. ”First they slander their victim, then they eliminate him.” He concluded: ”This time they’re really going to kill me.”

For many years, Falcone had known that he might be killed. But the soft-spoken, almost shy magistrate never wanted to be considered a hero. He insisted that he was just doing his job. As a magistrate and as a Sicilian he considered it his duty to fight the Mafia.