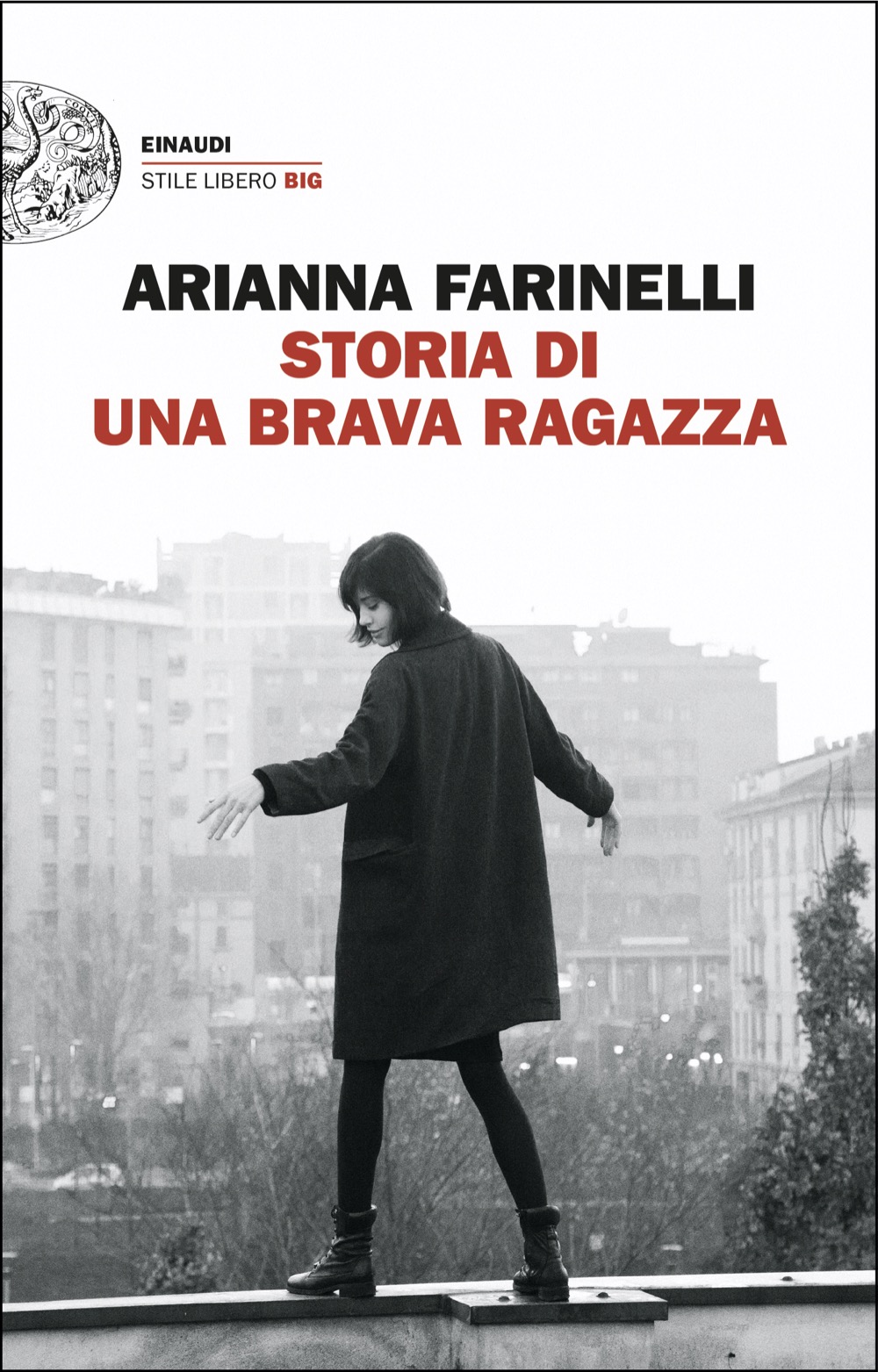

On May 7, at Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò in New York, in collaboration with Rizzoli Bookstore, Arianna Farinelli will present her new book, Storia di una brava ragazza (Einaudi, 2025), in conversation with Eugenio Refini. It’s a memoir that starts with the body, moves through shame, and grapples with a question that many women carry for decades: how do you stop being “good” and start being free?

The title is sharp by design. “Good girl” isn’t praise — it’s a form of control. The protagonist, a stand-in for the author, grows up in a working-class Roman neighborhood at the end of the 1970s. She’s raised on TV shows like Colpo grosso and in a family where words like “vagina” are never spoken. The culture around her is saturated with images of exposed breasts, lacquered lips, and legs in close-up — and yet, everywhere else, sex is wrapped in silence and shame.

The book opens with a child watching her mother undress and comparing that adult body to her own. A tunnel, a cave, a mystery. It’s the beginning of a long apprenticeship in what it means to inhabit a female body — a site of scrutiny, control, and projection. “It took me nearly fifty years to stop feeling ashamed,” Farinelli writes. “Women of my generation endured violence that went unspoken. Some managed to tell their stories, but they weren’t believed. That needs to change”.

This isn’t a book that tries to lecture. It simply shows what happens — to bodies, to girls, to women — in a system designed to mold them. “Beauty gave us value,” she writes, “and when we didn’t match the image on the magazine cover, we felt worthless.”

The girl grows up. She learns, questions, resists. She becomes a woman in a world that asks her to be visible only when pleasing, efficient but quiet. And even when she “succeeds” — moves to the U.S., builds a career, marries — patriarchy follows. It doesn’t disappear, it adapts. Less crude than in the Roman suburbs, but just as present in office emails and polite conversations. “At a dinner on the Upper East Side,” she recalls, “someone told me: ‘Women just aren’t good enough for top jobs.’ He wasn’t joking.”

What gives the book its weight isn’t ideology, but precision. The language is grounded, observational. Farinelli isn’t trying to persuade; she’s describing how structural power shapes personal experience. “My mother was a bartender who never finished high school. She didn’t know what feminism was, but she lived it. She pushed back against violence, against injustice. I only understood that much later.”

Women like her are at the center of the book — not theorists, but witnesses.

The memoir brings together a constellation of voices: Annie Ernaux, bell hooks, Virginia Woolf, Susan Sontag. They appear not as authorities, but as undercurrents — intellectual legacies felt more than cited.

Farinelli also writes for her daughter. And for the girls growing up today still being taught to smile, be thin, stay quiet. “I tried to turn disappointment into momentum,” she writes. “We need to give them a different future. Don’t do what I did. Don’t live asleep.”

There’s no heroism in this story, and no sweeping victory. Just an honest look at how complicity works — including among women. “Men are victims of patriarchy too,” she notes, “but that doesn’t make it less urgent to challenge it. I’ve doubted myself in every sexist situation I’ve been in — my judgment, my instincts. Like I’d been trained to self-correct before even speaking.”

The event will offer space to talk about shame, motherhood, education — and the everyday negotiations of power. Not symbolic freedom, but the kind that takes work. The kind that starts when you stop following the script.