What follows is an excerpt from ‘The Rome Guide’ by Mauro Lucentini, art columnist for La Voce di NewYork. More precisely, is an excerpt from those parts of the book entitled ‘Before Going’, that is which are meant to be read before the actual visit ,while the parts referring to the on-the-spot visit are labeled ‘On the Spot.’ This division is found throughout the book and is unique among guidebooks, being particularly suited to Rome, where it is extremely useful for absorbing the immense amount of information necessary to get an idea of the Eternal City and its 2700 years of history. All the excerpts to be published successively here will also come from the ‘Before Going’ sections. The complete book, including the essential ‘On the Spot’ portions, can be purchased on Amazon.

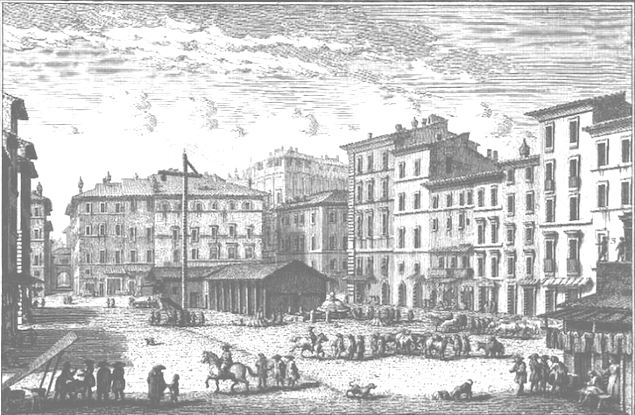

Campo de’ Fiori (‘Field of Flowers’) is named after the abandoned meadow which this area became in the Middle Ages. In ancient Rome it was a desolate neighbourhood, where the stables of the factiones, the racing teams of the Circus Maximus, were all located. (Their ruins have been found to stretch from Piazza Farnese to Piazza Cancelleria.) In the late 1400’s the pope decided to develop the area, the only rustic one that remained along the southern approaches to the Vatican. A new street, Via del Pellegrino (‘Pilgrim Street’, still eisting there), was driven through to ease traffic from the south, and sewers and other basic services were added. The square soon flourished. By the 1500’s it was considered the most important centre of city life, roughly comparable to the more commercial parts of the Forum in ancient Rome: a centre for markets, meetings, public discussions and important announcements. Public tortures and executions also took place here. Energetic activity went on all day, boosted by the passage of popes, kings and ambassadors, for the square was sometimes included in the ‘Via Papalis’ (from St. Peter’s to St. John’s). The major papal ‘bulls’ (edicts, so named after the large seal – bulla – attached to them) against heretics and rebels were hung up here. A 1739 bull raged against ‘licentiousness during the festival night of S. John’s. The last one, in 1860, promised eternal damnation to the patriots who were unifying Italy.

Until recently, almost every building around the square had an inn, as did many adjacent streets. The most notorious included the Taverna della Vacca (‘Inn of the Cow’) opened by Vannozza Catanei in 1513 after her almost official lover, Pope Alexander VI Borgia, died. A shrewd businesswoman who had outlived three husbands, in her old age Vannozza invested her considerable capital in real estate, hotels and inns. The ‘Vacca’ – said to be frequented especially by prostitutes – was amongst her most successful enterprises. She was a greedy old sinner, yet when she died five years later she left everything to religious institutions and charities. Her much eroded coat of arms, that includes allusions to the Pope’s, is still on the wall near the corner of the square where her inn once stood.

The piazza was an important arts and crafts centre, too, as witnessed by the names most streets around it still have (Baullari – ‘of the trunk-makers’; Cappellari – ‘of the hat-makers’; Giubbonari – ‘of the coat-makers’; Chiodaroli – ‘of the nail-makers’; Balestrari – ‘of the crossbow-makers’, and so on).

A very high gibbet loomed over the square until 1798. People were hanged by the arms from it for minor crimes. This ‘torment of the rope’ caused an excruciating shoulder dislocation. Via della Corda (‘of the Rope’) off this corner of the square is a reminder of this torture, not, as one might think, of the rope-makers’ craft.

Executions here took many forms. People were often hanged from windows. Three monks condemned for having tried to kill the pope with black magic were burnt on a pyre. The following entry from the meticulous diary of Johannes Burchard, the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies, reports an execution by garroting in 1498, which also reflects the racial, religious, social and sexual intolerance of the time:

April 9, Monday. (…) A courtesan, or honest prostitute, known as Corsetta, was arrested a few days ago for living with a Moor, who had been dressing as a woman.

Both were led around the city to show the scandal. She was wearing a black velvet dress … The Moor had his arms forced together and tied behind his back, while his gowns were hiked up to his navel, so all could see his testicles or genitals, making the deception clear. After the tour, Corsetta was released while the Moor was jailed in Tor di Nona [see Chap. 57a] until Saturday the 7th. Then he was taken from the prison along with two bandits. The three were led to Campo de’ Fiori by a constable on a donkey, who was carrying, at the end of a stick, the testicles of a Jew who had had intercourse with a Christian woman. The two brigands were immediately hanged, while the Moor was placed against a wooden plank and strangled against the gibbet by twisting a rope around his neck, with a stick from behind. A fire was made under him but it went out because it rained. His legs though, nearest to the fire, did turn to ashes.

Most memorable is the execution in 1600 of Italy’s greatest Renaissance philosopher, Giordano Bruno, who was burnt at the stake in the centre of Campo de’ Fiori for his very modern, materialistic conception of God as the universal soul of the world. Four hundred years later, the Church apologized for this and similar crimes.

What remains today of all these multifarious activities is a very colourful fruit and vegetable market, Rome’s largest, which has taken place in Campo de’ Fiori every morning except Sunday since 1869. The ubiquitous inns have given way to a few very popular restaurants and some food stores.

Right off Campo de’ Fiori is Palazzo della Cancelleria, by an unknown architect, Rome’s most splendid example of early-renaissance palace architecture. It is also a memento of the once inveterate habit of popes enriching their nephews (or in some cases their sons, since there were exceptions, some legitimate and others in defiance of the rule of celibacy amongst the clergy), a custom that gave us the word ‘nepotism.’ Often these youngsters received the rank of cardinal, too, and there even existed a quasi-official title of ‘cardinal nepote’.

One of the few positive results of nepotism is a group of beautiful Roman palaces built by these privileged relatives. The Cancelleria is the most magnificent. It was built in the late 1400’s by Cardinal Raffaele Riario, a nephew of Sixtus IV (whose portrait by Melozzo da Forlì is in the Vatican, surrounded by Raffaele and three other nephews, all cardinals or destined to be). Young Cardinal Raffaele invested not only his own funds in the palace, but also money he won from the nephew of his uncle’s successor, Innocent VIII, in a night at dice. Pope Innocent tried to recover his nephew’s money – 14,000 gold ducats, almost a million dollars today – but in vain, the money having already gone to the contractors. Cardinal Riario did not enjoy his palace for long, however. A few years later it was seized by Pope Leo X on account of the cardinal’s having known of a plot of the Riarios to unseat him without reporting it.

When Michelangelo arrived in Rome at the age of 21, he was introduced to Cardinal Riario, who housed him in an annex of his palace but was not otherwise very helpful. (Around this time, according to his biographer Vasari, and by his own admission, Michelangelo tried unsuccessfully to palm off to the cardinal a ‘sleeping cupid’ that he had carved and then antiqued in order to sell it for a higher price as a genuinely ancient piece. It was through the contacts made at Riario’s court, however, that Michelangelo received the commission for one of his greatest masterpieces, the Pietà, from a French cardinal, and it was this work that established his fame.

The palace interior is magnificent, but unfortunately closed to the public. Its most impressive features are a courtyard attributed to Bramante and a cycle of frescoes by the Florentine painter Vasari, who is also famous as a biographer of Renaissance artists. Forced to execute the frescoes in 100 days, Vasari was miserable about the results. An often told but apocryphal story is that he showed them to Michelangelo boasting of how quickly he had done them and Michelangelo replied ‘I can tell’. The frescoed room is now called ‘Gallery of the 100 days.’

For more than four centuries the palace has been the administrative offices (or ‘chancellery,’ hence its name) of the papacy and seat of its high court, the Sacra Rota (Latin for ‘Holy Commission’). The court still tries ecclesiastic suits here, though it lost most of its prime business, annulling marriages, when divorce was introduced in Italy in the 1970’s. The palace, together with the Vatican, enjoys extraterritorial status.

The Cancelleria encloses in its fabric one of Rome’s oldest churches, S. Lorenzo in Damaso. Digs in 1988 have revealed foundations more than 1,600 years old. Inscriptions found under the church show that in pagan times the area contained the barracks of the Green Team of the horse-drawn cart races, a team favored by the common people during the Empire.