A ghost is lurking like a black cloud over the potentially historical UN Climate Change Conference jointly co-sponsored by UK and Italy, just opened at Glasgow in Scotland, the proudly independent Celtic nation that, unlike England and Wales, soundly rejected Brexit. The ghost has an almost forgotten name: Inflation.

The two-week climate venue is ambitious and even utopian. But if it fails to cut down the anthropogenic emissions to as close to zero as possible, and therefore reduce global warming to a sustainable level, the prospects for future generations are going to be grim. For millions of humans, as scientists have warned, there will be no future on the planet.

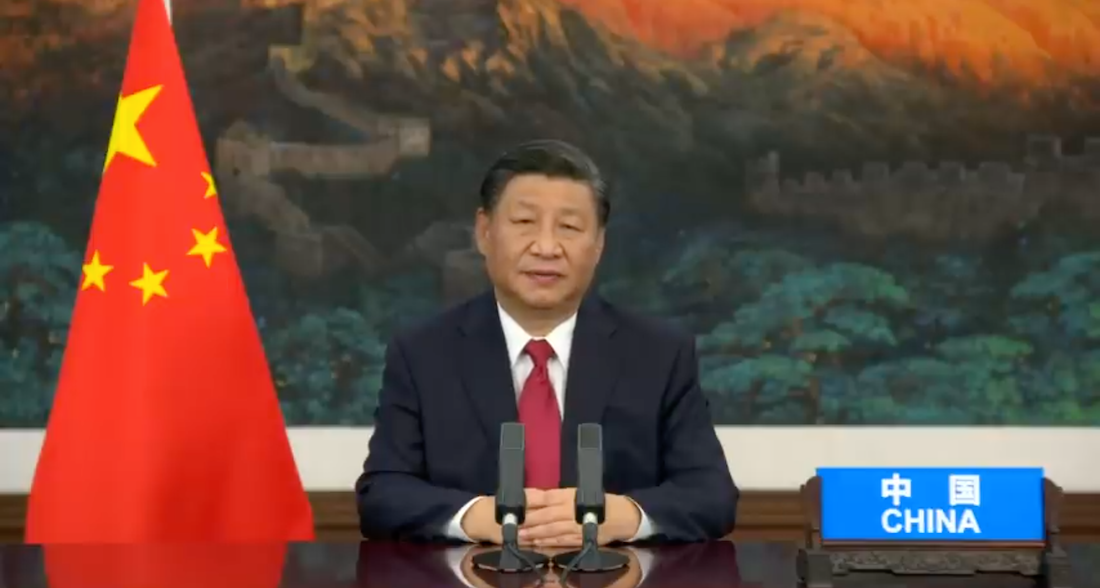

The omens are less than encouraging. Two of the world’s main polluters, China and Russia, have already politicized the issue, with presidents Xi and Putin who excused themselves for not being present. They object to an event that they see as largely stage-managed to protect the interests of the US and allies, while keeping the rest of the world on the sidelines.

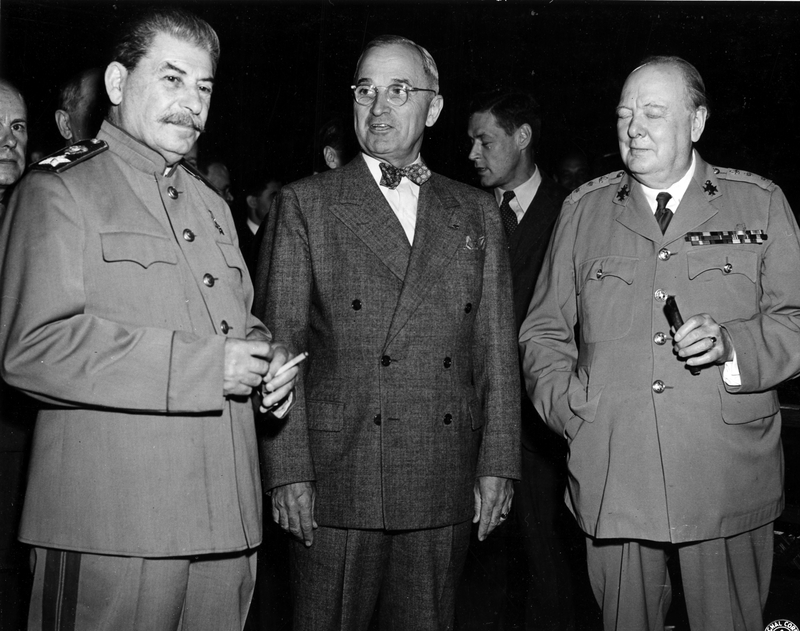

The argument, it must be admitted, is not without logic. But after all, world politics has always been the art of the possible. The long Glasgow summit is planned to end on November 12. If a compromise emerges, the meeting can always be extended. Indeed, this is what happened at San Francisco once, with a far from easy customer such as Stalin. Roosevelt and Churchill managed to accommodate the USSR’s views somehow — and eventually the United Nations was born.

But what does climate change have to do with inflation? Quite a lot in fact. Transitioning from the current industrial model, largely based on non-renewable fossil fuels, to a no-carbon economy, with the object of achieving the target of zero emissions by 2050, even if prices remain stable (which they are not) is going to be very expensive. Even in the richest industrial economies, what its technically known as “creeping inflation” is already a reality, with projected rates of increase of up to 4 to 5 per cent.

Now, with the already astronomical costs already sustained by governments, on account of the yet unresolved Covid-19 pandemic, by resorting to deficit-spending, which is graphically described by economist Milton Friedman as “helicopter money”, the question that will inevitably arise is: “Who is going to pay for the costly transition to non-fossil clean energy, and how?”

Present and future generations, unless a radically different set of rules of international trade and capital movements is set in place, will be stuck with an unsustainable burden for life. The danger is real. Even if moderate or creeping inflation may not yet be a cause for alarm to rich countries, in poorer countries the situation is already dire. As Italy’s premier Mario Draghi pointed out in his recent speech at the UN 76th General Assembly. Thanks to extreme weather and food supply disruptions, food prices had increased up to 32% as of last August, compared to the previous year. More than 2.3 billion people, according to FAO data, last year did not have access to food on a regular basis.

Meanwhile, memories of past inflation are fading away, in particular in the United States where the myth of the Almighty Dollar survives, even if inflation in reality was never defeated. With the paper dollar, made inconvertible by Nixon in 1970 but de facto universally accepted as a paper world currency, the system was bound to be unstable by definition. “It’s our money and that’s your problem” was the blunt response by the then secretary of Treasury Connolly at the G-10 monetary conference that took place in November 1971 in Rome, when America’s allies loudly complained that the US, by unilaterally devaluing their inconvertible currency by 15%, were in effect exporting their home inflation worldwide.

A few weeks later the same countries had to accept the dollar’s sharp devaluation as a ‘fait accompli’. The postwar artifice of the Gold-Exchange Standard born at Bretton Woods in 1944 with the solemn promise to convert every 35 paper dollars in circulation into an ounce of gold, was unceremoniously buried. Since then, the fundamentally flawed system known as Bretton Woods II has survived for half a century: as the French say, ‘faute de mieux’. This “dollar standard”, essentially on trust in the policies adopted by a supposedly benevolent superpower, was as irrational as choosing a piece of elastic as a unit of measurement. The US currency’s nearly universal acceptance prevailed on the sheer irrationality of the plan.

As distinguished monetary economist Professor Paola Subacchi of London University Queen Mary Global Policy Institute explains in two books that for scholars and policymakers ought to be mandatory reading, “The People’s Money: How China is Building a Global Currency” (Columbia University Press), and ‘The Cost of Free Money” (Yale), the Bretton Woods II non-system has three highly destabilizing effects: accelerated private capital flows ; burgeoning imbalances; and dramatically undervalued currencies.

Such is the dangerous disequilibrium in which the 21st century will have to survive. Multilateralism is the name of the game, with the United States no longer the unchallenged top player, China’s autocracy relentlessly forging ahead, the ancient and new demographic giants of Africa, Asia and the Southern Hemisphere reclaiming new roles and a more equitable redistribution of resources, managing instability and preventing new conflicts is the way the game will be played.

For the US superpower, sharply divided by populist sirens left and right, clinging to the outdated myths of American exceptionalism and the Almighty Dollar, by virtue of which debt either government or private does not matter, accepting the new realities will not be easy. With Covid, just to cite an example, the economy is kept afloat by running a colossal budget deficit of 12% of GDP. In addition, American families with unpaid rents, mortgages and credit cards, are wallowing in debt. Sadly, there is no magic “money tree” invented by benevolent governments. Inflation, as always, will impoverish the next generations.