The Adriatic Riviera (the coastal area on the Adriatic Sea near Rimini) as we know it today, was born in the climate of well-being and euphoria that characterized Italy from the end of the Fifties through the beginning of the Sixties, when the middle class generated mass tourism and the summer holiday took on the meaning of “escape” from everyday life.

Starting then, in Rimini, numerous areas equipped for sunbathing and welcoming holidaymakers were set up on the beach, first with moveable canopies and deck chairs and then with umbrellas and sunbeds and, in the areas of town closest to the sea, thousands of welcoming “all-inclusive” small pensions offering room and board at incredibly cheap prices, sprung up. They were all family-run, ready to host families and young people of all nationalities.

Paradoxically, the very Italian art of improvisation gave birth to what is still considered one of the most famous tourist resorts in the world today. At that time there were no hotel schools, and no one was trained on how to create a successful accommodation facility.

In the pensions—similar to today’s B&B’s–the women worked in the kitchen, their husbands at the reception, the children refurbished the rooms and served at the table during meals. Everything happened spontaneously, in that unique and magical period of economic rebirth called “Il Boom” or “Il miracolo economico,” (the economic miracle) of a country that had emerged as a heap of rubble after World War II.

In Rimini, another consequence of the development of mass tourism was the almost complete urbanization of the coast, with the creation of a single long linear city, born spontaneously; and with Miami Beach as a reference model.

The great success of Rimini as a destination for Italian and foreign tourists did not depend on the beauty of its coast but on the fact that a group of pioneers had decided to build Rimini’s tourism industry following the American model of customer satisfaction, by ensuring that products and services offered to the tourists met their demands and highest expectations.

In Rimini, the institutions and the different categories have always been able to work together as a team, and there has always been a unity of purpose between the political authorities, the hoteliers, the merchants, the shop owners, the lifeguards and the ordinary citizens, with the aim of doing everything that could be useful in order to allow a growing number of people to live well all year round despite the fact that the summer tourist season only lasted between 3 and 4 months. This also meant facilitating everyone’s work with measures that took into account the needs of shopkeepers to maximize sales opportunities during that limited period.

And, so, there were those who had observed the enormous numbers of people who crowded the Via Vespucci, the strip parallel to the sea overlooked by practically all the most prestigious hotels, every day. During the summer season this street was the favorite destination for afternoon and evening strolls and numerous tables turned it into a huge living room, starting at Marina Centro and continuing for kilometers along the coast in a southerly direction, towards Miramare. In addition to bars, ice cream parlors, game rooms and some notable dancing clubs, this important street was dotted with a myriad of shops, so it was decided to allow the shops to stay open in the evening until midnight and on weekends. This measure was rewarded with an exponential increase in business.

Subsequently, on the Romagna Coast it was decided to expand the leisure offer for tourists – beyond the beach in the daytime and the dancing clubs and huge discotheques at night – in particular for children and families, by investing in the creation of theme parks: first, two huge aquariums were built between the end of the Fifties and the beginning of the Sixties, then Fiabilandia, the first theme park inspired by Disneyland, was inaugurated; next came Italia in Miniatura, a sort of three-dimensional map of the Belpaese, on which over 200 of the most important Italian architectural wonders had been reproduced in scale all in just one place, and tourists could “visit” and appreciate them all, situated as they were just a few meters from each other.

Another successful idea was the enrichment and diversification of the entertainment offering with cultural proposals and this started with the restoration of the Gambalunga Library and continued with the reopening of the Castel Sismondo, built in medieval times, the redevelopment of the Piazza Malatesta, from the Renaissance period, the restoration of the fifteenth-century Malatesta Temple by the architect and art historian, Leon Battista Alberti, the restoration of all the villages in the hinterland, together with the creation of literary itineraries and wine routes. Exactly fifty years ago, the first international theater and dance festival was created in Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna, a small village just a few kilometers outside Rimini.

In the summers of the late Sixties, many Italians would abandon the cities and, for the first time, the media talked about an “exodus.” The great escape began on August 1, when all the main factories closed for an entire month. From the railway stations of Milan and Turin dozens of extraordinary convoys departed towards the South, with thousands of Southerners who had immigrated to the North returning home, and hundreds of thousands of cars, stacked bumper to bumper, inched along on the Autostrada del Sole.

The cities were completely abandoned, and even in Italy’s capital, Rome, all the bars and shops were closed, and it became impossible even to buy a pack of cigarettes.

The favorite destination of an overwhelming majority of holidaymakers was the sea. Many families stayed in a typical “all inclusive” pension, others in an apartment, while still others rented the same apartment every year, for the entire month of August.

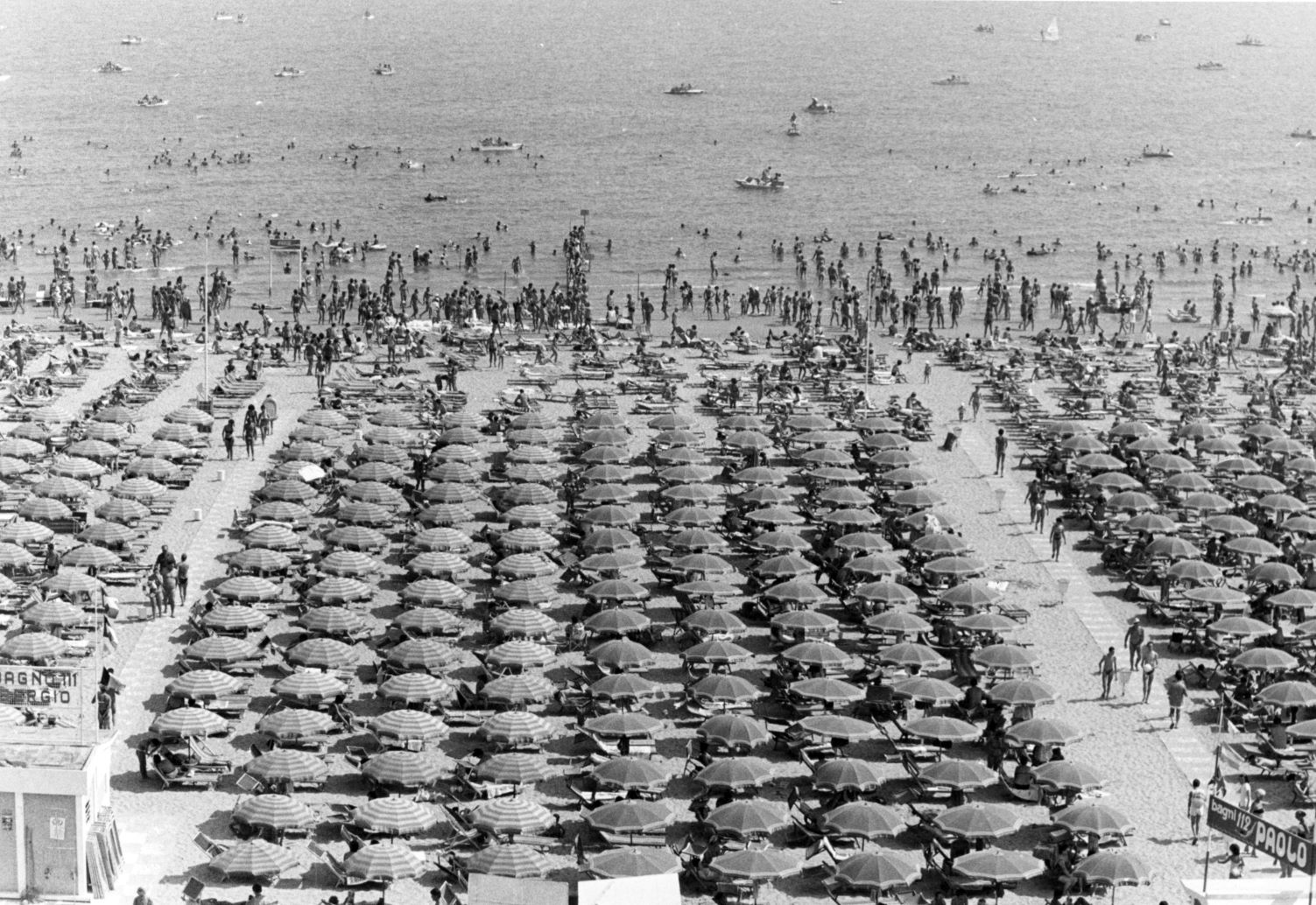

A summer holiday in Rimini meant going to the beach, at the establishment closest to one’s guesthouse or apartment; everyone settled on their sunbeds under the beach umbrella that had been rented for the entire month.

The big summer holiday, Ferragosto, was celebrated exactly in the middle of the month, on August 15th and for the two or three days around it, all pensions, hotels and holiday apartments were full and sold out on the Adriatic Riviera.

Even on Rimini’s huge beach there wasn’t a single centimeter left unoccupied by vacationers. The shoreline, where thousands of people normally walked back and forth, was occupied by people lying on sun loungers and towels, and to enter the sea it was necessary to do a sort of slalom around the bodies lying down, sitting or standing.

At Ferragosto, some beach attendants left a bottle of chilled white wine under every umbrella and in the afternoon, they offered everyone slices of watermelon. It was a tradition to have fireworks on the beach and parties in the dancing clubs. At midnight the singer of the band would interrupt the dances to invite everyone to a special toast.

Ferragosto was a turning point. “Il rientro,” the return to the cities, began on the first Sunday after August 15th, and for most Italians the beginning of September coincided with the end of that merry interlude of sun, swimming, companionship and lightheartedness. Summer loves inevitably ended. The cities filled up again, everyone went back to work, kids went back to school and normal life resumed.