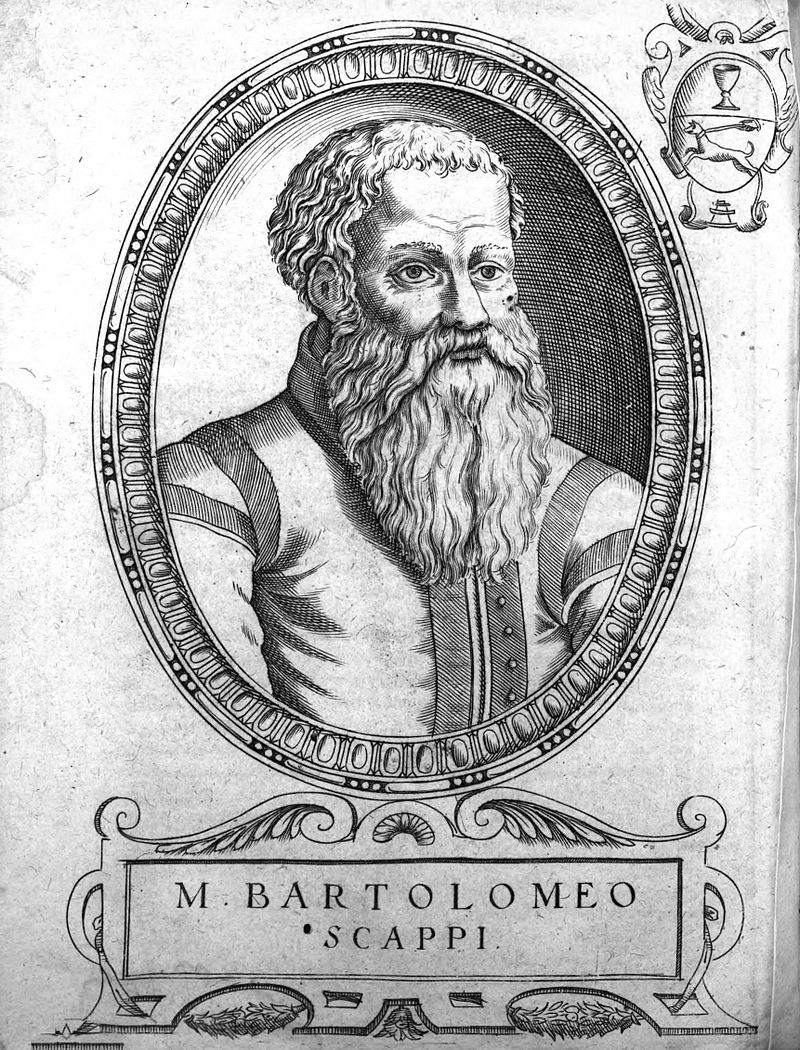

In my article “Rome’s Newest Museum, History Seen Through Kitchenware and Cookbooks”, published here in May 31, I mentioned that one of the Museum founder Rossano Boscolo’s most prized possessions, on display there, is Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera dell’arte del cucinare, the first illustrated (32 engravings) printed cookbook, dating to 1570. It was published in Rome in six volumes and contains over 1,000 recipes. Several of these include then recently discovered foodstuffs from the New World brought to Europe by the early Spanish explorers.

One of these foodstuffs is the pumpkin and Volume V’s 108th recipe is for an early version of pumpkin pie, which includes two types of cheese. The recipe translated and with commentary by Terence Scully in 2011 instructs: “When the pumpkin is scraped, cook it in a good meat broth or else in salted water and butter. Then put it in a strainer and squeeze the broth out of it. Grind it in a mortar along with, for every two pounds of pumpkin, a pound of fresh ricotta and a pound of creamy cheese that is not too salted. When everything is ground up, put it through a colander, adding in ten well-beaten eggs, a pound of ground sugar, an ounce of ground cinnamon, a pound of milk, four ounces of fresh butter and half an ounce of ginger. Have a tourte pan ready with six ounces of very hot butter in it and put the filling into it. Bake it in an oven or braise it, giving it a glazing with sugar and cinnamon. Serve it hot.”

Around the same time as Opera‘s publication, possibly even because of it, since Scappi was the chef to several popes, pumpkins began to be planted in Europe, apparently especially in England. So, although there is no evidence that the Pilgrim Fathers were familiar with pumpkins before they sailed on the “Mayflower” in 1620, they probably were. In fact, some scholars say that those who survived their first harsh Massachusetts winter did so because they ate pumpkins.

Like Scappi’s recipe we know that the Pilgrims’ first pumpkin dishes did not have crusts. The pumpkins were either stewed like a savory soup or their hollowed-out shell was filled with “the stew”, milk, honey and spices, and everything then baked under hot ashes.

The first recipe for pumpkin pie with a crust called “tourte” de pumpkin was published in 1651 by the famous French chef François Pierre de la Varenne (1618-78) and author of one of the most important French cookbooks of the 17th century, Le Vrai Cuisinier (The True French Cook). It was translated and published in England as The French Cook two years later. By the 1670s recipes for “pumpion pie” with cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves began to appear in English cookbooks like Hannah Woolley’s The Gentlewoman’s Companion (1765). Often their recipes added apples, raisins or currants to the filling. Finally in 1796 the first American cookbook with recipes for many foods native to the United States entitled American Cookery by an American Orphan named Amelia Simmons included recipes for pumpkin puddings with a crust, very similar to our present day pumpkin pies.

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that pumpkin pie took on a political significance, injected into the nation’s tumultuous debate over slavery. Many of the staunchest abolitionists from New England glorified pumpkin pie as their favorite dessert and it was soon mentioned in novels, poems, and broadsides. According to the website www.history.com/news/the-history-of-pumpkin-pie, “Sarah Josepha Hale, an abolitionist who worked for decades to have Thanksgiving proclaimed a national holiday, featured the pie in her 1827 anti-slavery novel, Norwood, describing a Thanksgiving table laden with desserts of every name and description—“yet the pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche”. In 1842 another abolitionist, Lydia Maria Child, wrote her famous poem about a New England Thanksgiving that began, “Over the River, and Through the Wood”, and ended with a shout, “Hurrah for the pumpkin pie.”

So it’s no wonder that in 1863 Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday, in spite Confederate protests that it was a move to impose Yankee traditions on the south, where instead a sweet potato pie was the tradition.

The world’s largest pumpkin pie was made on September 25, 2010 in New Bremen, Ohio, during the New Bremen Pumpkinfest. The pie consisted of 1,212 pounds of canned pumpkin, 109 gallons of evaporated milk, 2,796 eggs, 7 pounds of salt, 14.5 pounds of cinnamon, and 525 pounds of sugar. The pie weighed 3,699 pounds and measured 20 feet in diameter.

Other pumpkin facts: The Pumpkin Capital of the World is Morton, Illinois, the state that grows the most pumpkins, harvesting about 12,300 acres annually. The latest US record (2019) for the pumpkin ever grown weighed 2,517.5 pounds in Clarence Center, New York.

To return to Italy, pumpkin is an ubiquitous ingredient in dishes from all 20 Italian regions, but particularly in the north in risotti. In Reggio Emilia a version of pumpkin pie is prepared with amaretti (macaroons) and raisins and in Piemonte with Carpendù apples and other non-sweet fruits. Although not a pie, in Mantua and Brescia the local specialty are tortelli alla zucca (ravioli with pumpkin filling) and in the Veneto “suca baruca”, if not blended into soups, are either mixed in the “dough” for gnocchi or for polenta or are roasted strips or sugared fritters, both street food traditions in Chioggia, Padova and Venice. This odd name has two possible origins. One means a pumpkin or squash with “warts” in Veneto dialect, because their skins, often green or gray, have wart-like protuberances. Otherwise “suca baruca” may have been a specialty of the Jewish community in Venice where “baruch” means saint because “suca baruca” feed the hungry during winter. In any case, whatever its origin, “suca baruca” fritters were a favorite of the playwright Goldoni.