It would be difficult to imagine what the theater of dance, or theater tout court, of the last forty years would have been without the paradigmatic experience and creativity of Pina (Philippine) Bausch. Born in Solingen, Germany, on July 11, 1940, she passed away prematurely in Wuppertal on June 30, 2009 just when she was about to turn 68!. Pina the choreographer with an unmistakable black silhouette and anemic effigy, but actually a powerful and energetic leader of the dance theater genre (Tanztheater), managed to influence the cultural and aesthetic horizons of dance of our time. She attracted not only a host of imitators, but also an unsuspected public, perhaps the largest and newest than any other choreographer has attracted to themselves, at least when considering Europe.

It is comprehensible that the Old World began celebrating her tenth-anniversary festivities last year, by honoring the battle-cry “Join! The Nelken-Line” of the Pina Bausch Foundation, currently under the direction of her son, Rolf Salomon Bausch. Walking in single file, every-day citizens and dance lovers from many cities, not only Italian, have rebuilt and will continue to reconstruct several Nelken Lines, representing the unfolding of the four seasons through precise gestures, just as in the 1982 Nelken. We recall the stages covered with fresh carnations for each performance. In return, Rolf Bausch gave us an unexpected surprise: the opening of an on-line archive which he had immediately set to work on after the death of his mother. The enormous and complete legacy, available to scholars and others, includes 9,000 videos and 200,000 photographs: beginning with such early creations as Im Wind der Zeit (1969), a work that captured first prize in Cologne’s choreographic competition, and up to her last piece “…como el musguito en la piedra, ay si’, si’, si’… (2009),” dedicated to Chile. The latter, recalling her companion, Ronald Kay, refined Chilean writer who had been beside her for almost thirty years, vigilant, if only behind the scenes, and who was about to abandon her in that same year.

A cruel, even mocking destiny was reserved for her in that 2009, one that had been generous at the beginning of her career: in 1973, invited by the managing director the Wuppertal Theater, Arno Wüstenhöfer, Pina accepted the direction of the Wuppertal Ballet Company, knowing that she would soon rename it the Wuppertaler Tanztheater, using the same term, “theater of dance”, of her fellow choreographers working at that time in large structures and opera houses in West Germany. All of them grew up under the influence of the Expressionism of the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen, of Kurt Jooss, its most famous advocator and popularizer, and of Mary Wigman, a champion of the Ausdruckstanz (Expressive Dance). These artists were determined to demonstrate the diversity of their creations as compared to that of what the new ballet companies were imposing throughout the country, promoting a post-Holocaust cultural policy aimed at aligning themselves with the winning American way of life.

Pina, apparently timid, reserved, and not very eloquent– except after drinking a few glasses of wine and a festive dinner– never expressed anti-American political opinions. Indeed, she much was influenced by her residency of almost four years in New York, beginning in 1959 thanks to a scholarship as a “special student” at the Julliard School of Music. She also returned in 1962 with the conviction that German dance had not yet reached the American level of perfection. However, she was well-aware that her artistic roots came from Expressionism, and from research on the free, inner and spiritual dance of Rudolf von Laban, of which Jooss had been a pupil.

As her talent scout Jooss had done, Pina in Wuppertal set about searching for her own style, one that corresponded to her idea of “bringing dance closer to life,” of turning dancers into “people who dance”. This would mean jackets and pants for men, but above all, long evening dresses for women. It was a difficult undertaking, and perhaps it would not have succeeded without the scenographer Rolf Borzik and three dancers – the Czech Jan Minarik, and the French Malou Airaudo and Dominique Mercy – who urged her to start her long, gruelling journey, giving up dancing in the first person.

Her husband Borzik, who died in 1980, transformed the stage space for her, filling it with such natural elements as branch bundles for the opera-dance Orpheus und Eurydike by Gluck (1975); damp and fragrant earth in her fiery ritual The Rite of Spring of 1975; and dry and rustling leaves in the hall of Blaubart ( 1976). Then there were the tables and chairs in Café Müller, the Gasthaus in the autobiographical memory of the choreographer, the daughter of an innkeeper. Pina in a rare appearance, was seen with long, undulating, bony arms and eyes closed like the ghost of elsewhere. She was on stage again, but only years later, in Nur Du. Even Federico Fellini, who had a predilection for her, wanted her for the brief, yet incisive role of the blind Princess Lherimia in the film, E la nave va, his poetic homage to Opera and social change in society.

The Italian premiere of Cafè Müller in 1981, held at Teatro Due of Parma, was met with cold sarcasm, explaining, among other things, why the world-wide success of Frau Bausch was anything but immediate. Arlene Croce of The New Yorker wrote one of her most scathing reviews in 1984, “Bad Smell,” railing against all the Wuppertal productions. Similarly, the reception of Bochum of Bausch’s touching Er nimmt sie an der Hand und führt sie in das Schloos, die anderen folgen, a subjective version of Macbeth, as the long title suggests. It resulted in another failure.

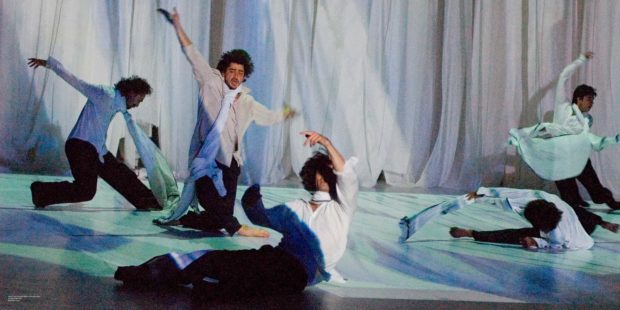

Yet, Bausch’s Tanztheater began to be understood in 1985; thanks to an extensive festival dedicated to her company by the “Teatro La Fenice” of Venice. This became the first occasion on which her new methods of working were unveiled. Born from the improvisation of dancers, and not from set movements and dance steps, it evolved instead from “questionnaires”. By instigating her troupe, which in the meantime had become international, Bausch ended up replacing original scores (for example, Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring) and dramatic texts (like Macbeth) of her first pièces, with a varied collage of answers to such questions as: “As a child, were you afraid of the dark?”, “What do you do when you like someone?”, “What is your greatest physical complex?” The striking result of this subverted choreographic practice did not consist, however, of only entering onto the scene screaming, making loud gestures, or singing to pronounced words and classical music, but also with reworked material.

Shows of the 1970’s and 1980’s such as Kontakthof, brought back at the beginning of the third millennium by a troupe of elderly amateurs, transformed into a “place of love” at the end of one’s life; or Bandoneon, where a Tango is danced seated; or Auf dem Gebierge hat Man ein Geschrei gehört, danced upon a stage filled with real very tall pines; and even Arien, submerged in water, allow us to relive Pina’s dreams and visions. All these works are shown through choreographic montages no less than perfect, and we are witness to what degree the artist had painfully been able to dig into the psyche of her performers, giving each one movements without masks, reconstructing the anomalies of social life in total mastery, waging the unresolved battle between the sexes, the disintegration of the more concrete values of the generation after the Holocaust, in a corollary of human vices and virtues of the German people, and not only German. All is accomplished beneath a powerful veil of amusement and irony.

It is enough to think of those triumphal “dance steps à la Bausch,” rhythmic and large-volume scrolling, with which she often sent her loyal dancers into the audience (as in 1980, a laid-back but bitter-sweet Hollywood style party), in a tactic to approach non-fiction, ever more insistent and physical. At the same time, she had capably transformed her first, unforgettable troupe into a sort of “family” of recognizable performers. It was a pleasure to rediscover them with the same obsessions, the small delusions or fears repeated from time to time in some new Stück or slice life.

Misguided interpretations of her work methods have attempted to place it within the world of the theater. In truth, Bausch has always preferred to be juxtaposed to music. During one of our unforgettable public conversations, she described herself as “composer of dance,” tracing the idea of the sub-title of her works, Stücke, to the traditions of Romantic music, to those “Variations on a theme” which for her meant dealing with life. In the creative arc that runs from 1980 to Palermo, Palermo, of 1989,wherein a large wall collapses at the show’s beginning, prophesying what was to occur shortly afterwards in Berlin–the great choreographer had built her major theater of dance in that rehearsal room of Wuppertal. However, it is also true that since Viktor (1987), inspired by the city of Rome, she had afforded herself the very German attraction of the exotic seeker of a journey in the style of Goethe.

By now, her scenographer had become the inseparable Peter Pabst, who contributed in fueling the dreamy spectacularism of new creations: in Madrid, Vienna, Los Angeles (Nur Dur, 1996), Hong Kong (Der Fensterputzer, 1997), Lisbon (Masurca Fogo, 1988, inserted by her friend Pedro Almodóvar in his film, Talk to Her), and again, Rome (O Dido, 1999), Brazil (Agua, 2001), Istanbul (Nefés, 2003) and India (Bamboo Blues, 2007).

All the same, with the loss of some of her long-time dancers and the entry of young members more eager to move than to be psychoanalyzed, virtual stage sets were introduced: stormy oceans, tropical forests, indigenous peoples, overwhelming nature. Strong images, a bit in tourist attraction style, accompanied by an almost uninterrupted coming and going of solos, especially by women, and without too many words. Pina was accused of lightness, and an all-too-easy cheerfulness, but she had been able to use the stimulus of social criticism, turning a hypersensitive 360-degree radar upon the whole of humanity, staunchly believing that by then, the only salvation for a world in decline was dance alone, and in a collage of electrifying music. Not by chance, Wim Wenders called his documentary in her honor not only Pina, but also Tanz, Tanz sonst du bist verloren (Dance, Dance, or You Are Lost).

Unfortunately, Wender’s motto of Pina in her last period, one that Nietzsche would have supported, seems not to have served to preserve the tranquility of the Wuppertaler Tanztheater, now struggling amidst political and legal intricacies. An institution conflicted about whether this is to become essentially a “dance-company-museum”, or to embrace the willingness to welcome new choreographers. The company faces a dismissed director, Adolphe Binder, who might return, and Bettina Wagner-Bergelt, a new leader who will bring them to Paris at the end of June with both Bon Voyage, Bob of the young Norwegian, Alain Lucien Ǿyen, and the magnificent Seit Sie (Since She) by Greek Dimitris Papaioannou, as wished by Binder.

This will be followed by a rich European calendar continuing until the end of 2020, with the resumption of such major pieces and rarities as The Seven Deadly Sins (1976). From April and May, it will be a return to the fields of the Sicilian havoc of Palermo, Palermo in Los Angeles, Berkeley and Chicago. Meanwhile, Rolf Salomon Bausch has already decided to set up a troupe of only black dancers for Le Sacre du printemps, premiering at Sadler’s Wells in London, in May 2020. His mother Pina rests in the flowery cemetery of Varresbeck, a neighborhood far from the center of Wuppertal. A visitor there will discover wonderful, always fresh flowers on her tombstone.