What follows is an excerpt from The Rome Guide by Mauro Lucentini and his co-authors. More precisely, it is an excerpt from those parts of the book entitled “Before Going” because they are meant to be read before the actual visit, while the parts referring to the on-the-spot visit are labeled “On the Spot.” This division is found throughout the book and is unique among guidebooks, being particularly suited to Rome, where it is extremely useful for absorbing the immense amount of information necessary to get an idea of the Eternal City and its 2,700 years of history. All the excerpts to be published successively here will also come from the “Before Going” sections. The complete book, including the essential “On the Spot”portions, can be purchased on Amazon.

This short stretch of our promenade includes two great churches of particular interest. The first is the only one in Rome dedicated to St. Augustine, the foremost ‘Teachers of the Church’, author of the Confessions and the City of God. The second is S. Luigi dei Francesi (St. Louis of the French), dedicated to a medieval French King and saint, Louis IX (St. Louis). The two churches share an immense privilege: they possess some of the most marvelous works of one of the greatest painters in the world history of art, Caravaggio. The present chapter concerns only the first of the two churches, St. Augustine (S. Agostino). But before we start, a few words about Caravaggio.

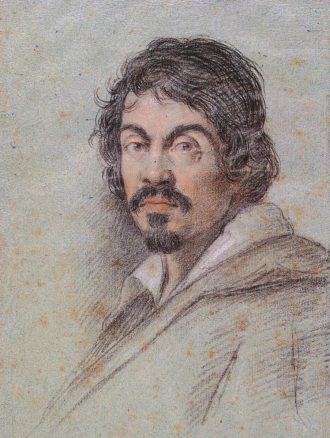

Michelangelo Merisi, called Caravaggio after his native town in Northern Italy, came to Rome in 1593 at the age of 20 and stayed for 13 years, producing masterworks that ushered in a new era in painting. A strange and violent man, always the odd one out, he was implicated in a series of incidents that culminated in his killing an opponent during a match of pallacorda or ‘rope-ball’, a sort of tennis, played by teams (Incidentally. the building where this took place still exists in Rome’s “Via della Pallacorda”)). Sentenced to death, he managed to escape Rome, wandering afterward, for four years, between Naples, Sicily, and Malta. Everywhere he went he left major works and indulged in bloody quarrels, one of which left him badly wounded. After partially recovering, he again headed for Rome, hoping for a papal pardon. On the way a minor accident stranded him – alone, ill and penniless – on a desolate beach north of the city. Delirious and tormented by the scorching sun, he died there at the age of thirty-nine.

His art, coming several decades after the measured equilibrium and splendid harmony of the Renaissance, starkly brings back the brutality of real life through several pictorial innovations. He used strong contrasts between light and shade (it was even said that he painted at night by torchlight). He also paid close, respectful attention to the humblest aspects of everyday life: the people in his paintings are always shown as ordinary and vulnerable, even if they are saints or the Madonna herself; and inanimate objects have the plasticity and weight of real matter. At the same time, his uncompromising realism is founded on a strong sense of the abstract values of drawing and composition. Few other painters have so vividly felt the latent geometry and interplay of shapes in the natural world.

This unprecedented blend of abstract and concrete may have been what particularly appealed to his fellow artists. His vision was widely imitated almost immediately, and its influence spread to most schools of painting all over Europe. To this day it carries a special charge, and admirers included artists such as Manet and Picasso.

St. Augustine, the adjacent Augustinian monastery and some of the nearby homes were a focus of Renaissance intellectual life, when many great artists, such as Raphael and Michelangelo, worshipped there. St. Augustine was also the preferred church of the famous courtesans. Artists and courtesans joined in lively discussions on art and literature at gatherings organized in nearby gardens owned by a high official of the Holy See, the Apostolic Protonotary, Johann Goritz, from Luxembourg (he was called Coricio in Rome). At their meetings, which ended in banquets, it was customary to read new poetry and to hang poems and garlands on trees. Some of these poems have survived. They typify the Renaissance spirit, exuding Christian sentiments dressed in pagan literary garb, with the Virgin extolled as a goddess and the saints as gods. As you will see in the last part of this chapter, there is also a work by Raphael, in St. Augustine, that might hint at the heterodox religious beliefs of the group of Catholic reformists, ‘the Spirituals’, of which Michelangelo was a leader.

The high-class courtesans who came to S. Agostino to pray and confess gave generously to the church and were often buried there in chapels donated by them and decorated with their funerary monuments. The most famous of them, Fiammetta Michaelis (commemorated by a square of today’s Rome, Piazza Fiammetta), was buried there. But these tombs, and possibly the remains, have entirely disappeared, no doubt swept away during the Counter-reformation.

To pass judgment on these remarkable figures of an extraordinary age is not easy. It is hard to draw a line between these courtesans and their thousands of poorer colleagues who plied their trade in the streets. Yet there was something spiritual about them that redeemed them in the eyes of their contemporaries, who commonly called them ‘honest courtesans’. Their beauty and perceived excellence exempted them from conventions. A comparison with Japan’s geishas might be apt. Highly polished, strikingly beautiful – a sharp-eyed man like the famous sculptor Benvenuto Cellini considered one of them, Antea, Rome’s most beautiful woman – they placed themselves firmly in the Renaissance ambiance of high culture and a passion for classical ideals of beauty and knowledge. This attitude could also invite ridicule, however: the scorching 16th-century satirist Aretino – a great writer but a spiteful man – gives us a devastating portrait of these women as a ludicrous blend of pretentiousness and greed, posing as heiresses to the famous hetæræ (‘companions’) of Greece and Rome. One, nicknamed ‘Matrema-non-vuole’ (‘Mummy-doesn’t-want-me-to’), afflicted clients with long recitations of passages from Latin classics (Woody Allen’s short story The Whore of Mensa comes to mind).

Yet many had true, even great literary talent, such as the poetesses Gaspara Stampa, Veronica Franco and Tullia d’Aragona, as well as Camilla da Pisa, who is remembered for her letters. Their intelligence and learning were often real. They were respected fixtures at the best parties and could hold their own in a conversation with the highest minds of that gloriously intellectual era. When they joined a permanent partner, they were expected to be faithful; hence Cellini’s murderous fury when he found his Pantasilea, a courtesan, with another man. The Church seems to have accepted them: they could be buried in St. Augustine rather than in unconsecrated ground in a special spot at the foot of the Toman Walls that was called “il Muro Malo” (the Evil Wall), as was prescribed by law for common prostitutes. These courtesans may even be considered proto-feminists, judging from the sonnet addressed to men by Veronica Franco:

Had we the arms and had we the expertise, Quando armate ed esperte ancor siam noi

We could hold our own with any man, Render buon conto a ciascun uom potemo

As we have hands, and feet, and hearts like you… Che mani e piedi e core avem qual voi…

Women have not realized it yet, Di ciò non se ne son le donne accorte

But should they once resolve on doing it, Che, se si risolvessero di farlo

They could fight with you men until they die. Con voi pugnar porian fino alla morte.

The aura of high learning around the church of St. Augustine is enhanced by the nearby Palazzo della Sapienza (‘Palace of Wisdom’), former seat of the University of Rome. a Renaissance building that saw lectures by famous scientists such as Galileo and Copernicus.

Going back to the interior of the church, another tremendous attraction is a fresco by Raphael of the Prophet Isaiah (1512), clearly inspired by Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes of prophets. Even so, the intense expression and the force of drawing betray the individuality of a great master. Michelangelo himself, no friend of Raphael, greatly admired the work. When the protonotary Coricio, who had commissioned the work, complained to Michelangelo that he had paid too much for it, the great artist replied: “The knee only of that image is worth what you paid”.

In the fresco, Isaiah carries a scroll in Hebrew with the biblical verse ‘Open the door to the believers’ under a dedication in Greek ‘to St. Anne, Mother of the Virgin, and to the Virgin, Mother of God.’ Below is the supporter’s name, ‘Io(hann) Cor(icio)’. In view of the recent theory on the political-theological reformist movement of Michelangelo and his friends, gli Spirituali (the Spirituals), the authors of this book propose that Coricio and – why not? – Raphael himself were part of the group. If that were so, then one might interpret this artwork exalting Belief as an expression of the importance of Faith as against the Church structure, the core tenet of the Spirituali. This semi-secret movement – certainly strengthened as its reaction to the Lutheran reform, but existing even before it – was so successful that when the English catholic cardinal Reginald Pole who was one of its leaders (the others were some Italian high prelates and the princess and poetess Vittoria Colonna) presented himself as a candidate for the Papacy during the conclave that followed the death of the current pope, he lost by a single vote. Had he won, history would probably have taken a different turn.