LEGGI QUESTO ARTICOLO IN ITALIANO

After his first stay in the lagoon city in 1880, in a big elegant apartment in the Berlendis palace (for the record, it is now on sale now for 2.5 million of euros,) Nietzsche wrote “If I had to look for a word to substitute ‘music,’ I would only use Venice.” Today, the Carnegie Hall chose to give tribute to the thousand-year-old history of the Serenissima with a musical festival that will take place from Feb. 3rd to the 21st.

During the Renaissance and beyond, no other city had so many opera theaters as Venice; Venetian scenic designs and prodigious theatrical machineries were admired and imitated everywhere, as an indication of style and technique. Even the craftsmanship was well-known: the musical instruments built in Venice were sought after by many musicians and collectors; since 1501, Ottaviano Petrucci realized a book containing 96 “harmonic music songs,” “Harmonice Musices Odhecaton,” the oldest example of printed polyphonic music, and Venice became the capital of the editorial music.

To avoid getting lost in the imaginary Calles – streets – of music, we took some “authorized personnel” as a guide, people that live in and among the notes and know how to narrate Venice the best, according to this declination.

Where Music is Born

Departing from the conservatory Benedetto Marcello, welcomed by the director Franco Rossi, also professor of History of Music, who tells us the news on the museum inside the conservatory, that has been recently expanded and re-opened to the public: “The new set up was necessary to valorize the exposed instruments and it was realized by Enrico Bertolotti, an alumnus of the school. The choice of cooperating with figures that form in our institution is a common characteristic for the music activities and that today can count on an interdisciplinary education, even with an organizational and cultural mark.

The museum exhibits about 70 instruments and various relics of the Venetian musical glories: “Among the most valuable instruments – continues Rossi – there are five double basses of great craftsmanship, created in different time periods between the 1600s and the beginning of the 1800s; moreover, thanks to their optimal state of conservation, some of those instruments are occasionally used in our concerts. Along with those double basses, a Venetian fortepiano (very rare, since the Viennese, English and French ones are much more common) and a precious polygonal spinet from the 1500 are very relevant. Along with the instruments, many relics are also preserved: autographs of various artists (among which Vivaldi’s, Liszt’s and Verdi’s,) Giuseppe Verdi’s original wax bust realized by Gemito (the two bronze copies are preserved at the conservatory of Milan and at the nursing home for musicians,) the baton with which Wagner directed the orchestra of the conservatory (at the time a musical high school) and other important portraits and relics.”

However, it’s outside the museum’s walls that Venice tells its story as a profoundly musical city. As historian and Venetian, Rossi recommends some of the most significant places: “Since Venice is an entire city of music, some of the places are of particular charm; obviously, the church of San Marco, whose choir was directed by the highest musicians of the time, from Willaert to Monteverdi, from Cavalli to Legrenzi, from Galuppi to Perosi. But also, many other churches: Saint John and Paul and the Frari: the first hosted the funerals of Igor Stravisnkij, the second hosts the burial of Caludio Monteverdi.”

And how can we forget the many theaters, starting from the famous Fenice (admirable example of restoration after the devastating fire in 1996) and Malibran, but that’s not all. “The relevant places for music are so many (hundreds of them recorded,) private as well; and naturally, our Pisani building, in which Napoleon was hosted, where Galuppi was professor of music and where during the entire 1900, without interruption, many major musicians were hosted. For example, there was a Vera Stravisnkij’s letter in which she remembers her and her husband stay in the concert room to attend an Andres Segovia’s concert.”

Among the greatest and most admirable Venetian buildings, the Pisani family’s building goes back to the 1600 and, in the centuries, it hosted kings and queens and other illustrious people. In the past, the “pòrtego”, the hall of the noble second floor, exposed the traits of the most eminent Pisanis; on the other side, there was the Galleria – the gallery – where an extraordinary collection was cultivated: from 1809 inventory, there is registry of 159 paintings, among which a Tiziano, Tintoretto, Veronese, Palma il Vecchio. However, the rapid fall of the family brought to the sale of both the abode, in 1816, and the paintings to pay the debts. Between the 1897 and the 1921, the City of Venice became, gradually, the only owner of the building, first as a location of the musical high school Benedetto Marcello, then, since 1940, a conservatory. In the palace there are still many treasures, from the chapel to the noble first floor, stuccos, inlaid doors.

At the conservatory Miranda Aureli teaches historical harpsichord keyboards, an instrument that, he explains, “owes a lot to Venice: from the first printed works for a keyboard instrument in 1517 to the development of the keyboard forms for excellence, that evolved from the organists of S. Mark during the 1500s and 1600s, from the use of it as an accompaniment instrument in the big operas by the most eminent composers, starting from Vivaldi, to the delightfully repertoire for harpsichord present in Galuppi and Marcello’s works, to mention only two of the most famous exponents of the Venetian harpsichord school of the 1700s.

A Sound Composition

The relationship between the city and music seems really natural to this place so unique and made of water and stone. Marco Bellussi, opera director, underlines “the luck of being born and raised in a magnificent art city, a place where every glimpse immediately acquires pictorial dignity, in which each sound is music already. I think about the swish of the canals, the oars that crackle on the forks and dive back into the water, the singing of the gondoliers and the verses of the flying seagulls. I could say that living in Venice is in itself an artistic and musical experience.”

Bellussi, a Venetian, active since 1995, created many productions both in Italy and abroad (Spain, Germany, Belgium, United States.) In his city, he collaborated with the main musical institutions as the Fenice, Biennale Musica and Galuppi festival; moreover, he staged Goldoni and Toniolo in theaters. Along to the opera directions, an important musical-literary piece dedicated to the Armenian genocide interpreted by Ottacia Piccolo and Emiliano De Lello stands out. “For over 20 years – tells Bellussi – I express myself through theater and music. I like to remember three significant meetings, that made me so proud of the work I have done in my and for my city: in 1996, I directed “La Serva Padrona” – “The Servant Turned Mistress” – by Pergolesi in a La Fenice production. The theater has just burned down and the opera contributed to collect the necessary money for the building’s rebirth. In 2011, I directed “L’Ultima Scena ed Evocazione di Rakewell” – “Last Scene and Rekewell’s Evocation” – for the Biennale Musica, a new composition by Stefao Bellon: deconstructing the last scene of Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” and contaminating it with “The Rake’s Progress” by Stravinsky, we represented the slow dozing off of human values in an emblematic location: the island of Saint Michael, which is Venice’s cemetery. Finally, in 2013, “Antony and Cleopatra” by Hasse at Labia palace.”

We are asking Marco Bellussi to bring us to his musical Venice as well, among the sceneries of this love story between the city and music: “Venice, as any other art city, has places that are institutionally dedicated to the music culture, places in which the offer to the public is guaranteed by both the continuity and the quality of the programs. Among these, I will suggest a visit to the Gran Teatro La Fenice, that offers a prestigious opera and symphonic season. Also, Venice can be proud of hosting one of the oldest musical choirs in the world, the Cappella Marciana, that for over 700 years accompanies the liturgy in the Saint Mark cathedral. Every Sunday at 10:30, Master Gemmani makes the golden domes of the cathedral resonate with Monteverdi, Gabrieli, Willaert’s articulated polyphonic twists. And if you would like to live a completely particular and intimate experience, I would suggest to look for the Pisani Ferri palace (right next to the conservatory) where Master Gobbo Trioli gave life to a unique and irrepressible musical gathering.

And music and culture are not only in Venice’s history: there could also be a future of a city whose beauty could possibly be also its condemnation. “Venice is a city with many strong points and just as many weaknesses – explains Bellussi – among those, the imminent danger of Venice’s degeneration, of losing its original lively and productive essence to become a sterile museum of itself needs to be taken into consideration. To avoid this risky tendency and possibly to contrast it, I would see the creation of spaces and opportunities for young students and new graduates at the Conservatory and the Academy of the Fine Arts with favor. It would be an intelligent way to create employment and, in the meantime, develop an innovative offer for tourists; an offer based on the local skills and talents.”

Music, Then and Now

Irene La Rosa, Marco Bellussi’s friend, architect, shared the artistic experiences as the scenic organization manager for the grand opera for the Galuppi Festival, dedicated to the composer from Burano and that was a member of the Choir of the University of Venice, taking part in many concerts both in Italy and abroad and recording two symphonic-choral CDs along with the Camerata Vocalis of the Tübingen University and the Orchestra of the Radio Tedesca Sudoccidentale (Südwestfdunk) – the South West German Radio. With overflowing dedication for the lagoon atmosphere, La Rosa tells us: “I had the luck of living and studying in one of the most magical and beautiful cities in the world. My memories go back to the decade of 1991-2001, when I lived there and I attended the university institution of architecture, the IUAV; Venice was always a musical experience, from the morning negotiations at the fish stands at the Rialto market, to the sound of the siren that announced the arrival of the acqua alta – the high water.”

La Rosa explains that, today, the system of acoustic signal alerts for the high water became even more complex and even more musical: when it reaches 110 cm., the sound is one extended “note,” at 120 cm., two ascending sounds, at 130 cm. three ascending sounds, at 140 cm. (and over) four ascending sounds. And the flow of musical memories starts again: “the give and take of the gondoliers to announce their presence at the corners of the congested internal canals with the typical Venetian expressions: ‘pope,’ ‘ohi!’ And the gabbling of the engines of the boats down the Grand Canal (topas, motor topas, taxis, motorboats and steamboats.)” In the long nights of Carnevalaltro, La Rosa recalls the image of a “thousands of young people who would follow a stereo-cart among “sconte“ Calles and “drunk” foundations, like rats behind the Pied Piper, to shout ‘oi ‘demo veder i Pin Floi’ by Pitura Freska – ‘hey, let’s go see the Pink Floyd’ – on top of their lungs and an entire local reggae repertoire that is one of the particularities of the contemporary compositions of the Venetian ambient, as the fame of the Vapore, a place in Marghera, testifies, that reminds me of a great night in which, during a 24-hour musical event in support of the Kurd cause, Simply Red came without any notice and played all night.”

Irene La Rosa’s elected places? “The Venetian fields, in which, as Alejandro Aqui’s student, I used to go dancing Argentinian tango with a stereo and my classmates, all night long; the Malibran theater, the theater at the Tese, situated inside the Arsenal and from which the 1500 tese – the depots where the sails were stretched out – on the Gaggiandre. And again, the Avogaria theater, memories of a professional collaboration with Stefano Poli, architect and son of founder of the theater, Giovanni, Giorgio Strehler’s great friend: our design table was Harry’s bar, of which he was a loyal customer.”

Musical Maps

Even with Paolo Cognolato, pianist and founder of the chamber music ensemble Interpreti veneziani – Venetian Interpreters – in 1987, we explore what he himself defines “one of the most important historical cities in the story of this art.” Cognolato underlines the richness of the Venetian musical scenario: “We all know about the musical activity of Venetians in 1700, a baroque period, characterized by famous names like Vivaldi, Albinoni, Galuppi, Marcello, and may other musicians, singers, composers who, with their works, filled the 17 theaters of the city.” But that’s not all: there were many other music places, like the Pietà church, situated where the Matropole Hotel is today, and it hosted all the “putte,” the young girls (mostly poor and orphans) that were started in the music world, with the life-long prohibition, however, of singing in theaters, except for the “daughters of the education, “daughters that have parents and were sent to those places specifically to study. “Vivaldi – tells Cognolato – worked at the church, but, at the same time, was an opera composer-entrepreneur at the San Angelo theater, that was substituted by a hotel as well. This is Venice’s best musical period, even though the 1600 works and Claudio Monteverdi’s vocal operas, Gabrieli’s organic repertoire (Giovanni, buried at the Frari church, and Andrea, his uncle, butied at Saint Stephen church) are not to underestimate.”

An epigraphic tour – one of the many opportunities of cultural wandering – reveals traces of artistic landscapes as the Neapolitan Domenico Cimarosa, who lived and died in 1801 at the Duodo palace, or Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who at 15 years old “festively” stayed at the Molin del Cuoridoro, in San Marco sestiere, during the 1771 Carnival as the plaque on the building remembers. The curious name goes back to the “cuoridori,” the golden leather makers (embellished leather also printed with decorative patterns, used in the past as furniture upholstery,) and that were kept in the workshop.

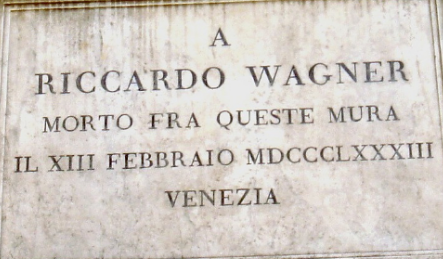

Richard Wagner, a loyal visitor of Venice, who arrived for the first time in August 1858, while composing “Tristan and Iseult,” and came back five times, the last time from Sept. 16th, 1882 to Feb. 13th, 1883, day of his death, at Vendramin palace. Only few weeks before, on December 24th, he celebrated his wife’s, Cosima, 50th birthday (Liszt’s daughter) dedicating her the “Symphony in C major,” personally directing at the Fenice, with the orchestra of the musical high school, in front of a small invited public; at the end of the performance, he donated his baton (the one mentioned above by Franco Rossi,) the music stand and a black beret.

Let’s go back to our stroll with Colognato and we get to the musical 1800s and, again, at the Fenice Theater that hosted some of the first Verdi’s operas, as the “La Traviata” – “The Fallen Woman” – and “Attila,” operatic drama, the latter that exalts the myth, rooted in the 10th century, of the foundation of Venice by the rural populations fleeing the Barbarian hordes. The most recent archaeological studies showed how the migration flows are chronologically stratified and not concentrated in one single moment, and how the water worked as a connection towards other frontiers and not as a natural obstacle for the enemies.

We get to the 1900s and to Igor Stravinskij, who died in 1971 in New York, and decided to be buried next to Djagilec, his collaborator, on the island of Saint Michael, where the central opera of his last period of activity, “The Rake’s Progress,” was born.

A museum, The Museum of Music, is dedicated to the love story between Venice and music, and consists of three collections: the main collection, according to the instruments shown, is preserved in Saint Maurice church (where Gian Antonio Selva, architect of the Fenice, rests since 1819); the ancient instrument collections from the 1600s that can be admired in Saint Giacomo di Rialto church; and, the last one, the collection of the important musical instrument of the luthery school of the Italian 1900s, that is collected in di Sain Vidal church, which was also the characteristic headquarters of the Interpreti veneziani, who, in their performances, renewed the glories of Antonio Vivaldi’s baroque music and the virtuosos of a particular repertoire present in the late 1800s and beginning 1900s, that contemplates Rossini, Paganini, De Falla, Serasate.

And while the music continues to fill the Venetian Calles, a piece of this story arrives in New York, thanks to the Carnegie Hall project.

LEGGI QUESTO ARTICOLO IN ITALIANO

Translation by Giulia Casati.