And God said, “Let there be light!” and there was light; however, it was neon and it was not God but Thomas Alva Edison who switched on the lights illuminating one of the most distinctive Art Deco buildings in New York City: the eponymous Edison Hotel

In New York City, Art Deco flourished in the Roaring Twenties. The unique combination of an exploding population, a booming economy, and cheap credit, together with the development of the elevator, steel-framed buildings and lax zoning regulations, created the most incredible transformation the city had ever seen. Majestic buildings, built only ten or twenty years earlier in a German Revival style such as the original Waldorf-Astoria, were suddenly considered “old”, as well as other buildings built in the Gothic, Victorian, and Classical-Revival styles. They went out of style and many were demolished to make room for the new Art Deco rulers of the city — the skyscrapers. However, to avoid New York from blocking off light and air, a new zoning design regulation was implemented, which required all the top floors of new tall buildings to “set-back” from the street line, which gave New York skyscrapers their uniquely Gotham look.

The iconic Art Deco buildings we admire today suddenly filled New York City: the Barclay-Vesey Building and 1 Wall Street, both designed by architect Thomas Walker, the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, the General Electric Building, Rockefeller Center, the Fuller Building, the Channing, the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and many others, with the Edison Hotel to be included among them.

The iconic Art Deco buildings we admire today suddenly filled New York City: the Barclay-Vesey Building and 1 Wall Street, both designed by architect Thomas Walker, the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, the General Electric Building, Rockefeller Center, the Fuller Building, the Channing, the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and many others, with the Edison Hotel to be included among them.

The architect Le Corbusier (who would have gladly bulldozed Paris and old New York) summed it up in one sentence: “In reality, the city is hardly more than twenty years old — that is the city which I am talking about, the city which is vertical and on the scale of the new times.”

The Edison Hotel opened in 1931 just off of Times Square on 228 West 47th Street — a perfect example of Art Deco style, with its many setback terraces. It is a vast building where the lower part of the façade is made of granite and the upper stories are made of white enamel brick with spandrels of polychrome terracotta. It could host 1,000 guests on twenty-six floors and had three restaurants and an amazing ballroom which was used as the Arena Theater in 1950 and the Edison Theater from 1972 until 1991. The hotel’s architect Herbert J. Krapp, was a theater architect and designer who had also built many of the amazing theaters surrounding Times Square, including the Majestic, the Biltmore, and the Imperial, just to mention a few, therefore making Broadway what it is today, and his style is also reflected in the Edison Theater.

Syncopated and jazzy, the Edison Hotel was the perfect backdrop for the 1930’s Metropolis. Batman could sometimes be spotted with his bat-wing-like cape (inspired by Leonardo Da Vinci’s sketch of an ornithopter flying device) patrolling Gotham perched on the shady set-back terraces of the top floors. However, perhaps distracted by the beams of the new neon lights of the city, he failed to notice some professional burglars stealing about $250,000 worth of jewelry from the apartment suite of Mrs. Lillian Kramer, the owner of the Edison Hotel.

Thomas Edison invented the movies; it is therefore only natural for the Edison Hotel to be featured in one of the most famous of all, “The Godfather”, when the hotel hallway leading to the lobby appeared in a very dramatic scene of the movie right before Luca Brasi’s execution. Then from “The Godfather” to “The God of our Fathers,” the play written by David Shayne, a fictional character in the Woody Allen movie “Bullets over Broadway” where scenes were filmed in the penthouse of the Edison Hotel. And even if Batman wasn’t in this case the right bird, how can we forget the scene with Michael Keaton in “The Birdman” filmed in the famous Rum House Bar, which was once affectionately described by the New York Times as “a shabby little piano bar off the lobby of the Edison Hotel… marvelous in its way as a place to stop in before a show for a whiskey sour.”

You cannot get any more Gotham than this, or maybe you can.

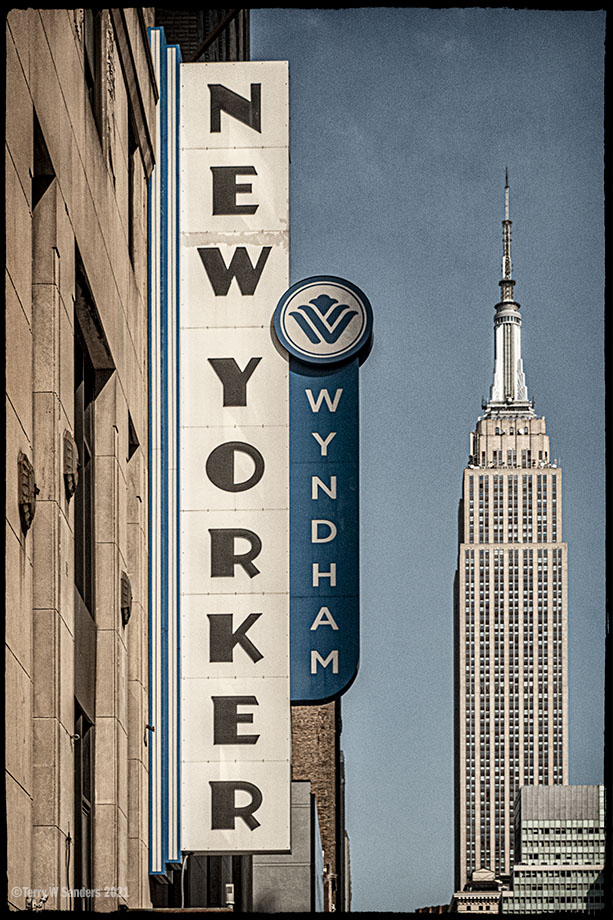

A real New Yorker can achieve anything by simply daring to think and act bigger, bolder, and better, and nothing could be more New York than the New Yorker Hotel itself.

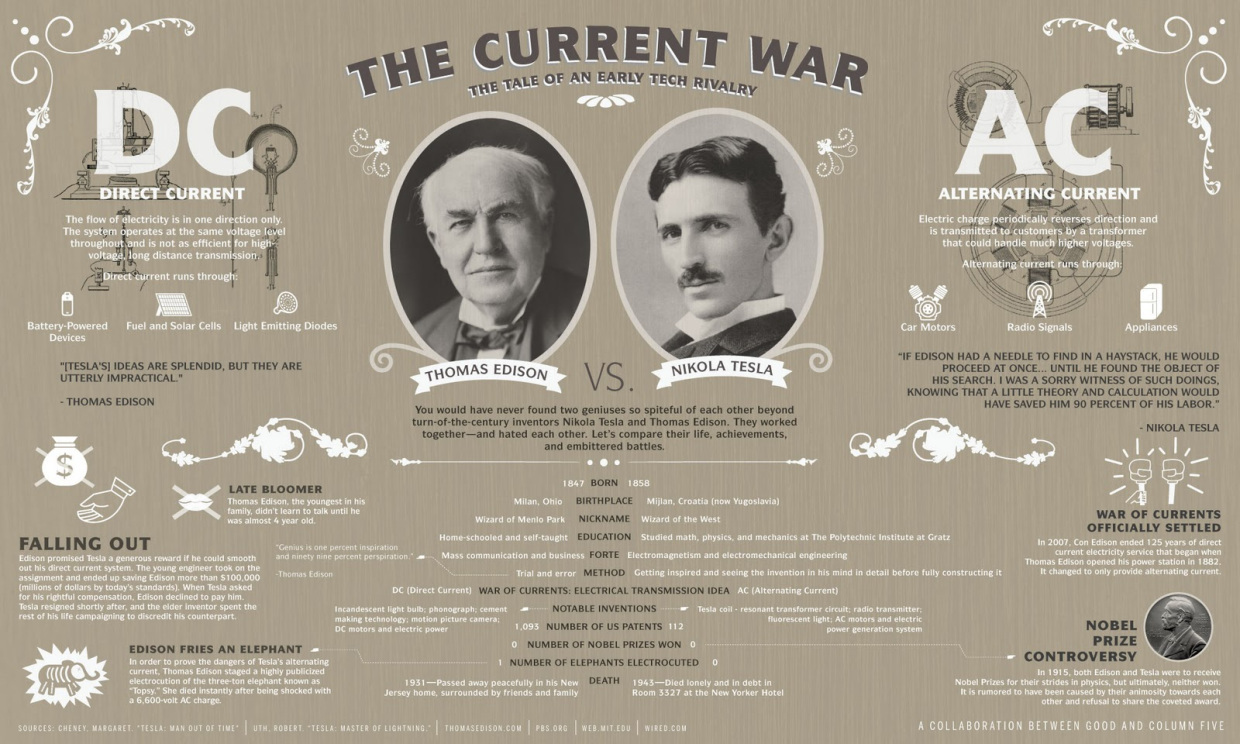

The Edison Hotel had inventor Thomas Edison to thank for its “visibility,” but when it comes to electricity there is AC and there is DC, so the New Yorker Hotel got itself nothing less than genius and rival inventor Nikola Tesla, inventor of AC power. In fact, Nikola Tesla lived in the New Yorker in room 3327 and 3328 (despite the hotel using the DC power invented by Edison) for the last ten years of his life, until his death in 1943.

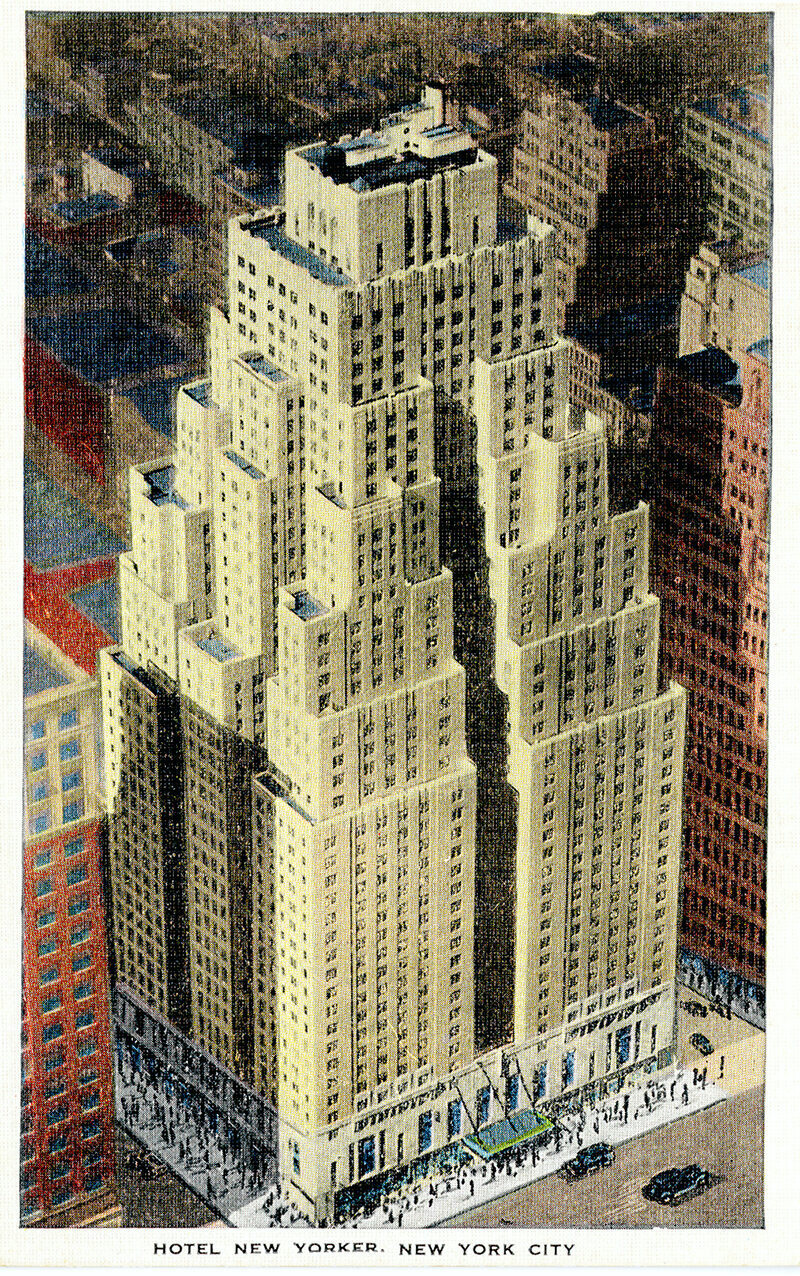

The massive New Yorker Hotel was certainly larger than any hotel ever built until then in New York City or pretty much anywhere else in the world. With its forty-three stories and 2,500 rooms it was a vertical city of a scale that no one had ever seen before. With its art-deco pyramidal set-back tower, it resembled the nearby Empire State Building. The New York Trust Bank was demolished to make room for the hotel, and another bank, The Manufacturers Trust Company, was supposed to be part of the new building, but it never happened, except for the beautiful Art Deco door and the vault with a massive safe that is still in the hotel.

The New Yorker provided amenities and services, delivered on a much larger scale. A tunnel ran underground directly from Pennsylvania Station to the lobby of the hotel and was decorated with splendid murals by Louis Jambor (now mostly painted over), and where twenty clerks were waiting to provide a smooth check-in to the arriving guests. There were twenty-three elevators that could transport 200,000 people in twenty-four hours, several ballrooms with a Grand Ballroom that could accommodate 1,000 guests for a dance or event, ten private dining rooms, five restaurants, a barber shop with forty-two chairs and twenty manicurists and ninety-two telephone operators just to mention a few details. It also had a radio in every room.

The New Yorker, like the Edison Hotel, opened during the Depression and never had the cachet of the posh Waldorf-Astoria or the St Regis — they were instead the hotels for regular Americans like the travelling salesman arriving in Penn Station, the GI waiting to be deployed or the out-of- state just-married couple visiting New York and celebrating at the Terrace Room with the popular bands of Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller or Bob Crosby playing at the New Yorker. Nevertheless, famous actors like Spencer Tracy and Joan Crawford stayed at the New Yorker, as did Barack Obama Sr. as a student in 1959.

Gotham is a city filled with light and energy felt by all New Yorkers, and, to be bolder, the New Yorker Hotel had a unique gigantic power plant built in the basement large enough to compete with the one at Niagara Falls. The power plant could generate electricity for a city of 35,000 and, for this reason, the New Yorker Hotel did not even appear on the map of New York City’s electrical grid. All of that energy did not keep the hotel from decline; Muhamad Ali was one of the last celebrities who, in 1971, stayed at the New Yorker just before it was sold in 1972 to be converted into a hospital. This time, it took, literally, divine intervention to switch the lights back on, in the form of the Unification Church of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, which purchased the building and in 1976 reopened the hotel.

The lights are on and electricity flows into the arteries of Gotham leading to Times Square, enough of it to power a city of 161,000 people. Our magnificent Art Deco skyscrapers are still the envy of other pedestrian, imitation skyscrapers everywhere else in the world. Batman got Superman to join him over the years and “The Daily Planet” just reported that the Edison and the New Yorker Hotel are alive and well, in case you missed the wonderful 1930’s bright neon sign that from the roof of the New Yorker Hotel, still shines proudly over Gotham.