The first World’s Fair in history – better known nowadays as Expo – took place, as everybody knows, in 1851 in London. For that occasion a famous greenhouse builder named Joseph Paxton planned the most extraordinary building of the Victorian Age: the enormous Crystal Palace. Only two years later the ocean would have been crossed for a second edition. The destination is New York where the intention was to build a more modest version of the crystal palace, on top of which a glass dome is added. The whole thing takes place in the middle of Manhattan, in what is now Bryant Park. In that same area a vertiginous tower of more than 100 meters is erected, the Latting observatory, which can be fully considered as the first skyscraper in history.

The sphere – a geometrical simplification of the dome – and the needle of the observatory represent – quoting Rem Koolhaas – “an archetypical contrast that will always reappear in Manhattan history” under new forms: the two extremes of the city’s formal vocabulary, which prophetically anticipate the future. Confirming this, in this very exposition, Leisha Otis presented a brilliant invention, which was beyond all doubt fundamental for architecture history: the emergency break for elevators. Otis makes the elevator a safe and extremely popular technology and from this moment on, buildings can begin their unstoppable vertical expansion, making effectively the 1853 exposition the birth of modern New York.

Some years later, the 1939 edition is held again in New York, this time not on Manhattan Island, but in Queens. More precisely in the area of Corona Dump in Flushing Meadows, where the very powerful Robert Moses, responsible for the organizational details of the fair, decides to build the new exhibition area.

The second fair’s theme was – not by coincidence – The World of Tomorrow and its symbols would be, again, a needle sided by a sphere: Trylon and Perishpere. These two iconic constructions were designed by the most famous architect at the time, Wallace Harrison. The same Wallace Harrison who had been seen working at the Rockefeller Center and who superintended the works from his office on the top of the Empire State Building, where he observed the progress of the sites through modern telescopes. The real protagonist of this edition would be architecture, also because in those years a passionate debate about what was modern was taking place. What was considered to be modern was coming out among several contradictions: magniloquent structures of classic influence, such as the imposing Russian Pavilion designed by Iofan, could be standing beside ultra-modern and humble set-ups, like the one that Alvar Aalto’s genius conceived for the Finnish Pavilion. The modest Italian building as well, Busiri Vici’s academic work, would definitely look obsolete compared to authentic modern work, like the Brazilian Pavilion, designed by a young and promising Oscar Niemeyer.

Curiously the most visited attraction was General Motor’s, which set up Futurama, an installation based on a huge tridimensional model. It prefigured a future city, more precisely a 1960 city, where the technology of interstates and buildings was a tangible anticipation of modernity, so tangible to give visitors at the exit a pin with the written: “I have seen the future”.

Since in 1939 the 60’s future was predicted with such an astonishing approximation, in 1964 a third World’s Fair was newly inaugurated in New York. Twenty four years later Robert Moses would still choose the site of the event proposing one again Flushing Meadows, where the sphere is again chosen as a symbol, as in a déjà vu. This time the sphere is embodied in the colossal metallic globe called Unisphere. It was conceived by Steel, Gilmor and Clark and it still dominates the Corona Park area. Futurama II, the most popular attraction of 1964’s fair, would complete the fil rouge of references and quotations: a re-proposition of the previous Futurama, which aim was to predict how our cities would have been in 1964.

Since in 1939 the 60’s future was predicted with such an astonishing approximation, in 1964 a third World’s Fair was newly inaugurated in New York. Twenty four years later Robert Moses would still choose the site of the event proposing one again Flushing Meadows, where the sphere is again chosen as a symbol, as in a déjà vu. This time the sphere is embodied in the colossal metallic globe called Unisphere. It was conceived by Steel, Gilmor and Clark and it still dominates the Corona Park area. Futurama II, the most popular attraction of 1964’s fair, would complete the fil rouge of references and quotations: a re-proposition of the previous Futurama, which aim was to predict how our cities would have been in 1964.

This last edition wouldn’t have the same impact that the one in 1939 had, and under the architectural quality point of view it was a marked step backwards. Nevertheless the New York State Pavilion by Philip Johnson and the futuristic IBM pavilion can’t be forgotten: the former with its flying saucers almost landed on thin towers, which constitute a pop-modern representation of the iconic “needle theme”; and the latter, the result of the fresh collaboration between Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames.

The aim being anticipating the future of our planet, it shouldn’t surprise if none of the initial expositions didn’t take place in Rome, a city which was not oriented towards modernity and pretty isolated. It would be 1911, the same year of the 50th anniversary of the Kingdom of Italy, in order for Rome to be able to host an Expo, not a “universal” one of course, but at least an international one. The program of this edition was structured and included several themes: an International Exposition of fine Arts, which was set in the extremely elegant area of Valle Giulia, a nice background for several of the many temporary national pavilions. Among all the pavilions, the Austrian one, designed by Joseph Hoffman, was striking. It was set in front of the new National Gallery of Modern Art.

Furthermore, there was an archeological exposition, which was set near the newly restored Diocletian’s baths and an Ethnographic Regional Exposition: a bizarre encyclopedic review of art treasures and of the usages and customs of the different cities that formed the Italian Kingdom.

Observing this section and comparing it to what was being built in that period in the rest of the world, there was a clear cultural gap between the provincial Rome and the other capitals of the world. The ethnographic exposition, hosted in the area that is now Piazza Mazzini in the Quartiere delle Vittorie, was constituted by several pavilions, each of which represented the local culture of a city. For example, Veneto chose to reproduce a cozy spot in Venice, complete with gondola and canal, in perfect Las Vegas style.

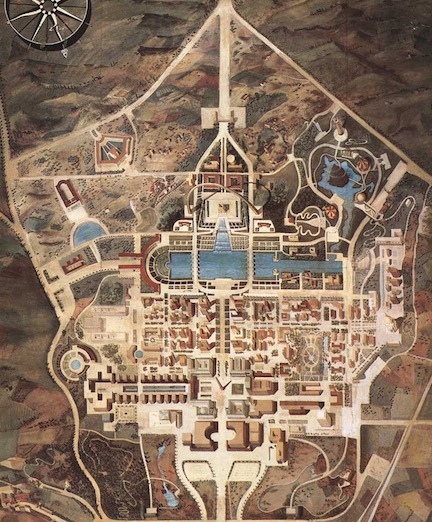

Besides the Disney-style tendencies, this exhibition was a good occasion to see the work of a really young architect, who designed the Palazzo delle Feste and the Foro delle Regioni. His name was Marcello Piacentini and 30 years later he would be the coordinator of the general project E42, an immense piece of work, a veritable city. It had been conceived to host the biggest exposition in history, a universal one this time, which should have been held in 1942 and celebrate the greatness of Italy and of the Fascist regime. The story behind it is well known, the tragedy of war stopped the realization of the work. At the end of the conflict, compared to the monumental marble and travertine city that Piacentini had originally planned – the “Third Rome that would have extended up to the Tirreno shores” – only a few buildings, two or three, had been made.

Besides the Disney-style tendencies, this exhibition was a good occasion to see the work of a really young architect, who designed the Palazzo delle Feste and the Foro delle Regioni. His name was Marcello Piacentini and 30 years later he would be the coordinator of the general project E42, an immense piece of work, a veritable city. It had been conceived to host the biggest exposition in history, a universal one this time, which should have been held in 1942 and celebrate the greatness of Italy and of the Fascist regime. The story behind it is well known, the tragedy of war stopped the realization of the work. At the end of the conflict, compared to the monumental marble and travertine city that Piacentini had originally planned – the “Third Rome that would have extended up to the Tirreno shores” – only a few buildings, two or three, had been made.

That of E42 was a weird fate: it was the symbol of the insane ambition of the regime, but it only remained on paper. It would be completed by the republican government in the years after the Second World War. They decided to continue the original project and put Marcello Piacentini himself in charge. E42’s name would change in Eur and finally it would host, in its everlasting monumental buildings, the International Fair of Agriculture in 1953 and the Olympic Games in 1960. This neighborhood, which was the only one in the history of Expos conceived to exist after the end of the event, was not inspired by the idea of modernity, but rather by the idea of eternity: it has indeed been able to survive, not only to men, but even to the gruesome ideologies that inspired it.

If today we observe an image of the ultra-modern monorail passing over the site of Flushing Meadows Expo in 1964, we will have the impression of being in front of a vintage picture: inspiring, melancholic and already passed. Eur, on the contrary and after all, still looks timeless, as if it was ready for the opening of a new Expo but at the same time as if it was the relics of an ancient past.

Traslated by Isabella Malacarne