In the attention we pay to Italian Americans, in justifiably honoring Joe DiMaggio and Fiorello LaGuardia, a central figure has been entirely missed, because few knew. It’s time for La VOCE to correct this.

In the great era of swing, in which big bands played to vast dancing crowds and jazz records sold like pop records, two bands dominated the scene. All other bands imitated, admired, and kept the doors of the clubs and ballrooms open until the next visit of one of the Big Two. One of these was the relaxed-but-fiery Count Basie band out of Kansas City. The other, the top of the heap, was the Duke Ellington Orchestra. (Benny Goodman came along a little later.)

Many critics and musicians favored the Basie band, which provided a driving foundation for the improvised solos that are the core of jazz. But, if ticket and record sales and the fees paid to the band are an indication, the Ellington Orchestra was the most important big band in America. It moved in an aura of sophistication and high culture. Dressed in tuxedos (Ellington himself favored white tuxedos with white shoes.), it had some aspects of a philharmonic: large formal compositions, with even the solos written out, bearing the titles of “suites” and “fantasies”. Where the Basie band featured spare, simple riffs as mere lead-ins to the important solos, Ellington and his colleagues wrote compositions and songs that flowed into the American songbook. At least twenty Ellington's pieces are still very widely played today, having become “standards”. Not so for Basie.

Ellington was so determined to fly at a lofty altitude that he called his band an “orchestra” and refused to use the word jazz, which sounded low-brow to him. So he declared that his orchestra didn’t play jazz (although it did), but played “Negro Music”, and he featured some pseudo-African motifs that attracted white exotica-seekers.

So why did so many seriously knowledgeable musicians and listeners prefer Basie? The answer lays mostly in a mysterious, ineffable quality that is central to most jazz. The quality of swing, not ‘Swing’ with a capital, which is a genre of music but swing; lower case, which describes that intoxicating, subtle quality that lifts one out of one’s seat, that starts fingers snapping (“popping” in jazz lingo), and produces that euphoria that can be found nowhere else. Jazz musicians shake their heads and become tongue-tied when asked to define it, and often use a variation on Louis Armstrong’s dictum that if you have to ask you’ll never know.

Central to the swing of a big band is the drummer. Swing is not just precise time; metronomes don’t swing. Through these years, the Basie band was propelled by the great Jo Jones, and then later by the fiercely-swinging Sonny Payne. But Duke Ellington had a problem. His heavy, complex compositions provided only occasional moments of freedom for serious swinging. But, at the center of any hope for that rhythmic lift-off was a drummer to whom Ellington showed rock-like loyalty through the years: Sonny Greer. Greer had been like a member of the family from Ellington’s early days in Washington right after World War I. He was a showman, twirling his sticks and always looking sharp. And he had good technique, playing with precise, straight-ahead time; which is different from swinging. Another difficulty was that Greer, during the two Swing decades, went from being a heavy drinker to being a serious alcoholic. By the late ‘40s he was falling apart, and Ellington had to hire a second drummer to provide the sure beat that Greer could no longer maintain.

It might not have mattered. The ballroom business was collapsing and, for many musicians, bands such as Ellington’s were becoming no more than part-time jobs. The Ellington band’s popularity was fading fast. And Greer’s collapse was now so obvious that, in 1951, despite Ellington’s decades-long loyalty, Greer was replaced with a drummer from the Harry James’ band named Louie Bellson.

Overnight, the band was transformed. Bellson was a driving, propulsive drummer whose swing was mesmerizing. Ellington called him “the epitome of perfection.” Bellson may have joined a sinking ship, but now it would go down swinging.

By the time Bellson left the band, (leading Ellington to lament, according to Ellington biographer Terry Teachout. “It’s going to be awfully difficult to replace him…He helped hold the band together as a unit with his drive and power.”), the band was on its way to enjoying a second round of prestige that nearly equaled the earlier glory. A smash Newport Jazz Festival performance, Time Magazine cover, and revived record sales (in the new long-play recording format) were on the immediate horizon.

There are two fascinating facts about Louie Bellson, the man largely responsible for the revival of America’s most popular jazz orchestra. First, this driving, swinging drummer who propelled the most extravagantly-swinging period of Duke Ellington’s “Negro Music” orchestra, was white, the first white musician Ellington ever hired. It meant that Bellson had to share all the pain and insult suffered by a black band whose touring schedule included the South. But it also meant that Duke Ellington had to eat a lot of his words about who could play this music. Ellington wound up calling Bellson “not only the world’s greatest drummer … but the world’s greatest musician.”

The second interesting fact about this historic jazz figure is very little known. Louie Bellson was only a stage name. His real name was Luigi Paulino Alfredo Francesco Antonio Balassoni.

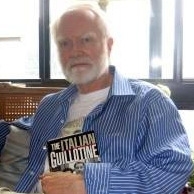

* Former Director of Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and author of The Italian Guillottine: Operation Clean Hands and the Overthrow of Italy's First Republic (Rowman & Little Field, 1998).

* Former Director of Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and author of The Italian Guillottine: Operation Clean Hands and the Overthrow of Italy's First Republic (Rowman & Little Field, 1998).