Built by the emperor Vespasiano in 72 B.C., the Coliseum is without a doubt one of the most famous arenas in history and, in the subsequent two millennia, has inspired architects who have been tasked with the duty of designing a stadium. Across the world, and particularly in the United States, the facilities that carry the name “Coliseum” are innumerable, but it’s now back in Rome that American architect Dan Meis is inspired by the beloved Flavian Amphitheatre to create a new sports facility for the home team of the capital.

It seems definite that with the 2016-17 season, As Roma Football Club will dismiss the Olympic stadium to debut in the new structure owned by the team. Time has made it obvious that the existing stadiums in Rome, the Olympic Stadium and the Flaminio, are no longer adequate to receive the multitude of fans which, for many years now, has had a significant impact on the traffic and safety of the surrounding neighborhoods. Building a new stadium with innovative solutions and up to the high standards of every modern city (above all in terms of security) now seems to be indispensable for the public interest.

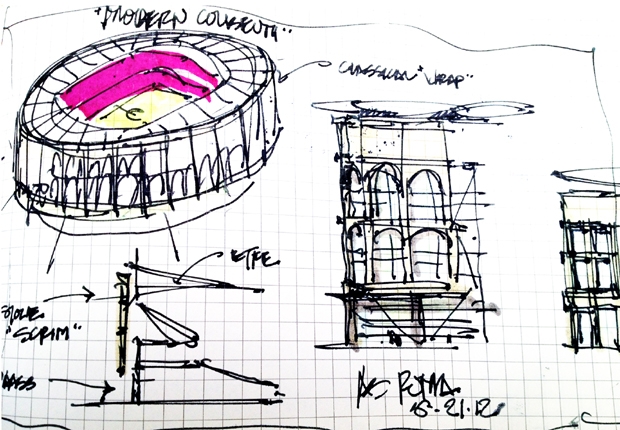

The Californian firm of Dan Meis has specialized in arena design for many years: they have built sport facilities all around the world and it is specifically for this reason that the management (notably also American) of the team ‘giallorosso’ has turned to this studio to undertake the design of the new stadium. The design is ambitious: the Coliseum 2.0 will rise within the next three years in the Tor di Valle area, with a new structure that has a capacity of 55-60 thousand people and will cost over 300 million euros. Around this will be a new sports center, commercial center, museum, hotels and two skyscrapers by Daniel Libeskind. The entire project is an investment that will exceed a billion euros, all privately subsidised.

It’s important to highlight that the good intentions of the As Roma Football Club owners, apparently uninformed of the latest events of the city, from building speculations of the ‘60s and ‘70s to the more recent “Mafia Capitale” investigations, are fueling questions of urban, environmental and even moral scales.

For Roma’s new stadium, a futuristic structure is being proposed, not innovative but rather conventional from the architectural point of view. The stadium will be a perfect oval, with a light structure, raised from the street and with an elevation characterized by diagonal ribs and a red roof that will be illuminated in the night. Three rings of stands (finally close to the field), the unmistakable skyboxes (extremely expensive balconies for the more wealthy fans), restaurants, shops, and everything else that results in today’s ‘modern’ arenas. All around the “Roma Village”, with much greenery but also many supporting structures dedicated to fans and families: an active area of entertainment with many boutiques, restaurants and event spaces.

For Roma’s new stadium, a futuristic structure is being proposed, not innovative but rather conventional from the architectural point of view. The stadium will be a perfect oval, with a light structure, raised from the street and with an elevation characterized by diagonal ribs and a red roof that will be illuminated in the night. Three rings of stands (finally close to the field), the unmistakable skyboxes (extremely expensive balconies for the more wealthy fans), restaurants, shops, and everything else that results in today’s ‘modern’ arenas. All around the “Roma Village”, with much greenery but also many supporting structures dedicated to fans and families: an active area of entertainment with many boutiques, restaurants and event spaces.

The exterior appearance of the stadium makes an obvious reference to the ancient Coliseum, with its facade that is in large part covered in stone, reminiscent of the three levels of Vespasiano’s arena. There is also a nod to the angled buttress, a work of Giuseppe Valadier which, in 1823, was a necessary addition to the ancient structure to prevent it from falling into further ruin. This aspect, though subtle, suggests a deeper reflection: the Coliseum, a historical symbol of the sporting arena, somewhat disregards its own history since its original state is no longer relevant, compared to how it is marketed as a symbol on a global level.

But all of this is not surprising, and, on the contrary, is ultimately quite understandable. Without giving a verdict, we can affirm that sporting events play in contemporary society the ‘secular’ role which in ancient times was reserved for the epic poetry. But today’s contemporary heroes and mythical stories are the world champions, revered and celebrated across the globe. As such, the sporting event must have a setting, a kind of theatre that lives up to this. Some believe that today’s global architectural languages have ceased to rise to this occasion, thus requiring for us to turn to models of the past to retrieve and rekindle this “sacredness”.

Something of this nature took place in New York. It was November 8th, 2008 when a small group comprised of kids from the Bronx, the former players of the Yankees that won the ultimate title in Major League Baseball, and the team owners crossed 161st Street carrying with them the home plate and mound of the old stadium (which was about to be demolished) into the new building on the other side of the street as it was about to be inaugurated. It brings a smile to think that such a procession, which in spirit was almost a religious one, crossed a street to move two objects that, at first glance, could have been easily replaced with new indistinguishable ones. Yet it felt necessary to express this secular sacredness that sports embody in America, where the history doesn’t have ancient roots and these events represent a deeper role in popular culture.

Something of this nature took place in New York. It was November 8th, 2008 when a small group comprised of kids from the Bronx, the former players of the Yankees that won the ultimate title in Major League Baseball, and the team owners crossed 161st Street carrying with them the home plate and mound of the old stadium (which was about to be demolished) into the new building on the other side of the street as it was about to be inaugurated. It brings a smile to think that such a procession, which in spirit was almost a religious one, crossed a street to move two objects that, at first glance, could have been easily replaced with new indistinguishable ones. Yet it felt necessary to express this secular sacredness that sports embody in America, where the history doesn’t have ancient roots and these events represent a deeper role in popular culture.

If baseball in the most widespread sport in the Unites States, the New York Yankees is the team that is most famous and “richest in history” of the country. Their stadium is much more than just sporting facility, but rather one of the monuments of the city. Built in 1923, the Yankee Stadium was often called “The House That Ruth Built”. The first game that took place was, in fact, a victory that the Yankees had against the Boston Red Sox thanks to three home runs from Babe Ruth, the most famous baseball player in the history of the sport, traded to the New York team a few weeks prior from the very same rival team, the Red Sox. The new stadium, designed by the office Populous, a kind of multinational of sport facility architecture based out of Kansas City with satellite offices all over the world, couldn’t disregard the history and meaning of the old stadium which was to be completely demolished. Since keeping the old structure would have been economically unfeasible, it was decided to at least preserve the idea that the old stadium embodied.

In this way, similar to Rome and its new stadium, similar dimensions for the playing field were maintained, with the same configuration for the stands and even the same orientation of the original structure. One can even find that some stylistic-architectonic qualities of the facade were reproduced: full-height narrow arched openings (nod to the Coliseum) and the wood “frieze” which, in the old stadium, characterized the roof covering the stands that we can find, albeit in steel, in the new construction. The modern architecture, which in the last century denied any kind of ornament that was not structurally necessary, seems to make an exception when it comes to arenas since, as we’ve seen in the past with cathedrals, when close to the playing field, the fan, like any faithful follower, recognizes symbols of his or her faith. Moreover, paraphrasing the great David Foster Wallace, the sport is a “bloody near-religious experience”.

In this way, similar to Rome and its new stadium, similar dimensions for the playing field were maintained, with the same configuration for the stands and even the same orientation of the original structure. One can even find that some stylistic-architectonic qualities of the facade were reproduced: full-height narrow arched openings (nod to the Coliseum) and the wood “frieze” which, in the old stadium, characterized the roof covering the stands that we can find, albeit in steel, in the new construction. The modern architecture, which in the last century denied any kind of ornament that was not structurally necessary, seems to make an exception when it comes to arenas since, as we’ve seen in the past with cathedrals, when close to the playing field, the fan, like any faithful follower, recognizes symbols of his or her faith. Moreover, paraphrasing the great David Foster Wallace, the sport is a “bloody near-religious experience”.

Traduzione dall'italiano di Christine Djerrahian.