On July 2, 1961, in his home in Ketcham, Idaho, Nobel Prize author Ernest Hemingway put a rifle to his head and pulled the trigger. So ended the life of a troubled, and troubling, writer and human being.

This year we are commemorating the 60th anniversary of this event that shocked the world. Strangely though, this was the second time that Hemingway “died”. The first was in 1954 when sightseeing in a small plane in the Belgian Congo, the plane crashed and he and his wife Mary were believed to have perished. Newspapers were writing him off as “feared dead.” The next day while flying towards medical help in Uganda, that plane crashed too. Two plane crashes in two days and he didn’t die. This is pretty emblematic of the kind of drama that was Hem’s life. He was master of his life and death—or so he thought–and only he could end it, and eventually he did.

In all the seminars that I have taught over 30 years plus of teaching, the reaction to Hemingway has never wavered: the women in the class generally loathed him for his misogyny and braggadocio, and the men admired him for his “bravado” and wanted to be him.

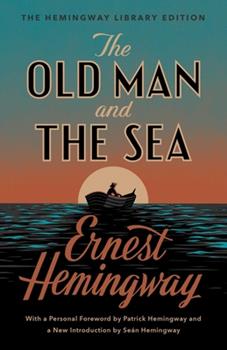

Ken Burns’ recent documentary revisits many of the anecdotes and critiques of Hemingway’s life and works, but most critics concurred that his writing was brilliant, innovative, insightful of the human condition, and that he probably deserved the accolade of “best writer of the 20th century”. His first novel, The Sun Also Rises, captured the desolation, psychological trauma and emotional bankruptcy of the post-WWI period, the so-called “lost generation,” and put him on the road to recognition and fame.  A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, To Have and Have Not, Hemingway produced one critically acclaimed best seller after another for decades. With Across the River and Into the Trees the magic spell was broken and he came to know firsthand the desperation of the author abandoned by the Muse. Yet he bounced back and produced his masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954.

A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, To Have and Have Not, Hemingway produced one critically acclaimed best seller after another for decades. With Across the River and Into the Trees the magic spell was broken and he came to know firsthand the desperation of the author abandoned by the Muse. Yet he bounced back and produced his masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954.

But as a human being Hemingway was flawed to the point where it interferes with the readers’ enjoyment of his work. In one extreme case, one of my graduate students so hated him and his posturing that he wanted to visit Ketcham, Idaho, just to “dance on his grave.” This pretty much encapsulates Ernest Hemingway for the public and the critics. But of course, there’s much more to it than that.

We all know on some level that as readers or audience, we have no right to interject our knowledge of the artist’s biography into the evaluation of their work. We’re still debating this very question in regards to Woody Allen and the subject of pedophilia and sexual molestation. The artist’s work ought to be judged independently of his personal morality. But can we actually succeed in doing this? And should we?

At what point does the artist’s life become irremediably entangled with their work? The Hemingway legacy is an example of how difficult it is to sever the connection between the artist and his personal life. Ernest Hemingway was an ungrateful friend, cheating husband, indifferent father and hate-filled son. Starting with the first of these, he never failed to repay a friend who had helped him with humiliation and cruelty. Those who helped him to get noticed and then published, like Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein and especially F. Scott Fitzgerald, were later publicly satirized, ridiculed, or shamed (respectively).

He cheated on Hadley Richardson (his first wife) with Pauline Pfeiffer, her best friend, who became his second wife. In turn he cheated on Pauline and married his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, who was then ignominiously thrown over for his last wife, Mary Walsh. He had multiple lovers all the while being married to all four of them and in his marriage to Mary, he abused her not only verbally but physically as well. Throughout these acts of cruelty and disloyalty, he found ways to rationalize them and persisted in blaming the victims for having caused them. He referred to his mother Grace, as an “all-time American bitch” and hated her to her—and his–dying day.

No doubt this hatred of his mother was the root cause of the misogyny that ran as the undercurrent in all his novels and that led to the unmitigated hatred that feminists had for him and/or his novels. With a few exceptions, the women in his novels victimize and destroy their men. They are usually portrayed as being weak, deceiving, or sexually promiscuous while the men carry all the admirable qualities: strong, brave, true and loyal—to their male friends and to themselves.

And yet there is no denying that his work has defined literature in the 20th century more than any other author. F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway were contemporaries. Indeed, when Fitzgerald wrote The Great Gatsby Hemingway was still writing for newspapers and trying to free himself from the drudgery that kept him from spreading his literary wings. Hemingway was inspired by that novel to write one of his own, and Fitzgerald gave him friendship, editorial advice and a recommendation to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, who then published what turned out to be Hemingway’s break-out work.

These two men were at opposite poles of the spectrum in every way, but stylistically, while Fitz’s prose is known for its poetic inflection and sheer beauty, and muses on the collective human condition, Hemingway’s banished most of the flow and rhythm—and adjectives too—and scrutinized the individual’s experience. Short and concise to the point of needing the reader’s implicit collaboration to construe its full narrative, Hemingway named it the “iceberg theory”: only one eighth needed to show on the surface.

But in the attempt to wrest Hemingway’s work from his life we are hampered by the fact that his fiction, even more than for other authors, is inextricably tied to his biography. This is not surprising of course. All good stories bear true-to-life immediacy and in any case a good writer must draw on what he knows and feels. But this is even more true for Hemingway. Philip Young, a literary critic and authority on Ernest Hemingway, concurs and has written that, “Many of the stories…are very literal translations of some of the most important events in Hemingway’s own life.”

The protagonist of most of the stories of In Our Time for example, is Nick Adams, a barely disguised autobiographical figure who embodies his early life and experiences in Illinois, Michigan and World War I. Clint Kalbach enumerates all the ways that Hemingway’s last masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea is an account of his life at the time; indeed, it’s “an allegory of his career”, his psychological and emotional state and his various disappointments.

Hemingway the person was Hemingway the writer’s best subject. But at some point, the dividing line between his life and his fiction became blurred. Fiction and reality became tangled with each other. Thanks to mental illness–a genetic curse in his family that led to the suicide of himself, his father, his brother, his granddaughter Margaux, and 4 other members of the family, he lost the battle to keep the two separate.

Throughout his life he had cultivated—some would say invented or even mythologized—an image of himself that bore little likeness to reality, and if he was unsuccessful at separating the supremely flawed human being from the gifted author, how can we? Perhaps we can’t, and perhaps we don’t need to. We can read the works of the master, enjoy them, and at least try to think of them as fiction.