The 1907 Monongah explosions may be remembered for Italian deaths that exceeded those in 1956 Marcinelle. It may better serve us to remember the West Virginia disaster for the way body pieces were assembled, covered and paraded with a deception so grand that pieces of assembled flesh were given Italian names or for the Monongah myths imported into Italian society or for the Italian women, widowed and deceived by the Monongah disaster, their lives left unrevealed.

Grandpa Tropea taught me things I will never forget, about a president named for a type of pasta, Abraham Linguine, and about the Monongah disaster. Grandpa worked in those mines and he gently pressed into my heart feelings for so many sons, husbands, fathers, cugini and paesani obliterated in a few seconds – and those miners who were not reported.

Those unreported miners remained in my memory and, years later, I tried to identify them. After many interviews, much archival work and trips to Italy, I found no supporting evidence for those miners and, reluctantly, realized it was a myth that, like other parts of Monongah lore, would be imported into Italy and embellished. During the disaster’s centennial, charlatans inflated the number of unreported dead miners from over one hundred to well over six hundred, including mythical donne and bambini.

The Italian government gave credence and posterity to those unreported miners with words on a Monongah monument with the caveat that only God knows the “true number.” This kind of inanity must be countered with research-based understandings of the Monongah disaster to honor the men who died and the women made widows.

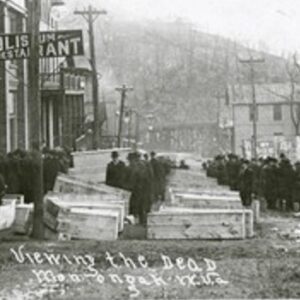

Central to understanding the disaster is the documentation of horrors and deceptions in managing the recovery, in the identification and burial of dead miners. When American men went into the mines to recover bodies, they often found only bits of detached, splattered and mixed flesh of miners and draft-animals.

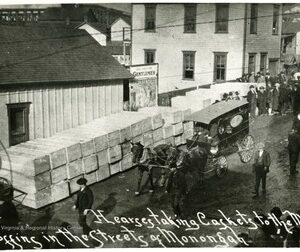

Partial cadavers, as well as mixed pieces of the dead, were collected, assembled and covered. Exposing the realities under the sheets was neither useful nor humane; this would have made worse the grief and confusion of persons waiting, weeping and hoping for familiar bodies to mourn, not fragments of carnage. Also, it would have been diabolical to speak in the presence of families and children of “bits of splattered flesh,” so, the recovery workers used a metaphor: “body,” for the reality of body parts and pieces, shaped into body-forms, sheathed and carried into the light of public grieving.

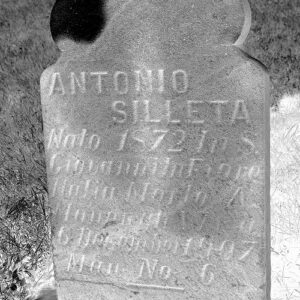

Morgue personnel accepted “bodies” brought from the mines, more to name than to identify them; the payroll office provided a list of miners’ names for this purpose. The naming of unidentifiable remains was the core of a grand deception, the source of much of our inherited confusion; for example, in the recovery, a mismatch developed when the morgue had unused names and the cemetery had unnamed remains.

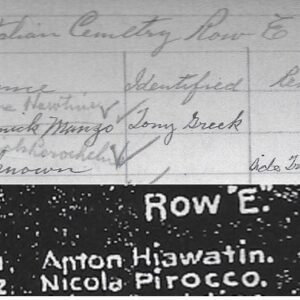

The solution was simple yet bewildering: attach the morgue’s unused names to the cemetery’s unnamed remains. Documents show that miners’ names were used to replace other names already assigned to remains, as well as to give names to “unknown“ remains, with many such “bodies” already buried. For a confusing example, Nicola Pirrocco was believed to be dead because his “body” was recorded as “unidentified;” yet, months after the explosions, Pirrocco’s “body” was recovered from a mine, “identified” and “buried.” Nicola Pirrocco was “buried” is known because his name was used to replace “unknown” for remains already buried in Grave 2, Row E, in the Italian cemetery.

Documentation of the “backstage” management of the Monongah dead helps understand how intricate are the sources of our confusions and myths.

Research challenges the belief in reported, as well as unreported, dead miners. Louis Patch is on the official list of the Monongah dead. The body of Louie Patch was reported to have been taken out of Mine 8, the 151st overall. The company also wrote one letter describing Louis Patch and certifying his death and another letter noting he was buried in “E 2” – the same grave was also associated with “unknown” remains and the name of Nicola Pirrocco. While this suggests a problem, the fiasco of Louis Patch’s death was fully revealed when we: uncovered his Italian identity, Luigi Pace; visited his paese, Civitella Roveto; spoke to a woman, who remembered Luigi and his Monongah stories; searched the commune’s records, which showed Luigi Pace married a year after the Monongah disaster; and met two members of Pace’s family, who confirmed his life in Civitella. The explanation is simple but troubling, when thinking about miners’ deaths. The “checks” miners placed when they entered the mines were scattered or destroyed by the explosions. Without these “checks,” the company used mainly verbal reports of missing miners and sought their names in the payroll records. When there was a match, it was concluded that the miner had died; even the English-named Italian who had departed for Civitella, not Mine 8.

While it is important to identify bases for our confusions and myths, Monongah research would be incomplete without substantiating the lives and experiences of persons who lived and received the brunt of the disaster’s horrors and deceptions – the women widowed by the disaster. These mainly migrant women were neither consulted during the after math, nor their lives explored later, to help understand the aftermath and its consequences. Instead, they were patronized in reporting their gestures and emotions, ridiculed in interpretations of their grave-side behavior and described in callous and ethnocentric ways in relief reports and ignored by scholars.

We explored the lives of many Italian women, widowed by the disaster, and thus far have published articles on three, Maria, Catterina and Rosa. This research made our knowledge of the Monongah aftermath more robust, rigorous and personal but, as importantly, the women’s lives informed us of much else, before and after the disaster, often about unexpected matters. We uncovered: very different responses to their dead men; more precise documentation of the “body” deception and its personal effects – short-term and long-term; the travails, challenges and ridicules endured by an Italian widow in making a life for her children; scandal, shame, divorce, lost custody and vulnerabilities of a white widow; and much else that will not be discussed, like, “a ‘mbasciata,” spousal abuse and death in a family and court; patterns of health, accident and death for paesani women and children, incidents of wife replacement and leasing of, and cohabitation in company houses and much else that expanded our knowledge of Monongah, its effects and migrant lives.

Maria Gaetani Abbate arrived in Monongah at the age of 43 in 1906, a year before the mine explosions, more settled in her Italian rural ways than most other women in her situation. That December 6th morning in 1907, Maria was washing clothes outside Company House 177 with five of her children, when underground explosions threw them all to the ground, swung the laundry kettle and killed her husband, brother, two sons and a boarder. Maria would recognize only the body of her fourteen-year-old son, Giuseppe, who died from asphyxiation, not from the force of the explosions. There is no convincing evidence that the bodies of Maria’s other son, husband, brother or boarder were brought out of the mines; maybe parts or pieces were gathered and bundled. The death of Maria’s brother was not recognized until six months after the explosions but, nonetheless, five caskets were delivered to Company House 177; one with Giuseppe’s body and the other four with whatever was gathered. Particulars in the “recovery,” “identification” and “burial” indicate the grotesque and intricate deceptions that shaped Maria’s sorrows, confusions and, ultimately, confounded her life.

The loss of Giuseppe was wrenching enough but lacked the tortured fabrications of what was in the other four caskets.

Maria’s nineteen-year-old son, Carlo, and husband, Francesco, are noted, respectively, to have been the 127th and 263rd bodies brought out of the mines. However, these notations are suspect: they come from the records that show Luigi Pace was the 151st body brought out of the mines. Also, no one is recorded to have identified the body of the son or father; yet, their names replaced “unknown” remains buried in the Italian cemetery, Carlo for remains in Row B, Grave Site 14 and Francesco’s for remains in Row F, Grave Site 4.

While there is no record that the body of the boarder, Francesco Todero, was brought out of the mines, his name, nonetheless, was used for Row G, Grave Site 15, while another document shows a second miner, “Francesco Antonio Guarascio,” occupies the same grave. Again, while there is no notation that Maria’s brother was ever brought out of the mines and his death was not officially recognized until months after the explosions, a bastardization of his name, “Frank Gatano,” was used to replace the name of another miner already listed for Row B, Grave Site 3.

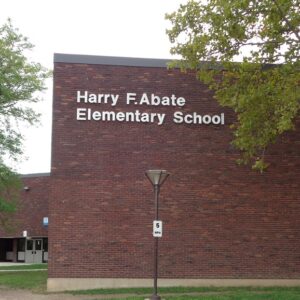

These machinations, in addition to the relief part of the aftermath, deeply unsettled Maria, affected her decisions about leaving Monongah, leaving a forwarding address, going to Niagara Falls where a brother lived, dealing with her eldest daughter, who refused to return to Italy, and Maria’s departure for Italy and subsequent return to Niagara Falls. A granddaughter corroborated Maria’s lack of competence in organizing her life after Monongah and this granddaughter also remembered tales of the poignant occasions when Maria and the “old people” recalled the disaster, accompanied with subdued weeping for four of the lost men but not for Giuseppe, who received intense grieving with loving remembrance of his pristine body. (Note: research on Maria was possible after we learned a Niagara Falls school was named after her youngest son, who was thrown to the ground in Monongah.

I first learned of all the Monongah widows through archived records, except for the “crazy lady,” who, for decades, walked 2-3 times a day to gather coal near the mine and carry it in a sack back to her house. I remembered her trips from childhood tales, the reason she was widely known in Monongah, called “Ciuccia” (donkey) by local boys, cartooned in a syndicated column and considered strange. When Catterina DeCarlo Davia died in 1936, some folks also remembered her from being widowed by the 1907 disaster and from rejecting what the company said were the remains of her husband. Otherwise, her life was little known, steeped in legends of her coal-carrying behavior. Those legends long remained but were modified to better fit the disaster’s centennial ceremonies and to contribute some substantive narrative for a “Monongah Heroine” statute, vacuously dedicated to “beloved widows.”

To account for the embarrassingly large mound of coal she left in her backyard at the time of her death, Catterina was largely transformed from zany to love-obsessed with her dead husband. When some Italian charlatans heard this legend, they embellished it with a woman possessed of a love so strong that the backyard mound of coal became a “collina dell’amore,” certainly not an ample reserve of energy for heating and cooking.

Through research, from interviewing Catterina’s grandsons and Monongah neighbors to visiting Domegge di Cadore and working with documents in Italy and the US, we substantiated a remarkable woman, not a heroine made in legend. If Catterina achieves heroic status, it will be for her energy, independence, perseverance, wise decisions and devotion to her children. She showed these qualities in the early moments of her widowhood, not only in defying the authorities over the identity of a “body” but also in the plans she made and then realized through her strength and wise choices in the face of adversity, even if called a ciuccia or considered pazza.

Shortly after settlement with the authorities, Catterina left Monongah, departed New York for Le Havre and crossed an ocean and the Alps with her five young children to arrive at her paese in the Dolomites. Catterina resided in the United States for thirteen years and needed to assess paese options for her family. When she arrived in Domegge, near Austria, there was famine. Catterina, without revealing her possession of relief monies, quickly decided to return to Monongah. She then suffered the procedures necessary for a woman without a man to exit Italy and, after visiting various authorities and locations and securing documents, left the Alps and, again, crossed the ocean with her children, this time in the middle of winter. When the family arrived, they were not allowed to enter the US: one of her children was ill and West Virginia could not provide birth records for some of the children. After rejecting the possibility of a life in her village, an exhausting return voyage and an additional six-week delay, spent in the Ellis Island hospital and waiting for papers to enter the US, Catterina returned to Monongah, undeterred. Then, two weeks after admission to the country, Catterina bought a house in Monongah, where she raised chickens, planted a garden, preserved foods and made lots of polenta, which enabled survival and a life for her children – including daily trips to gather free coal for heating and cooking. Legends failed to mention the discipline, tenacity and practical intelligence of a widow called “ciuccia.”

Brief excerpts from the lives of Italian migrant woman can be misleading. For example, the story told here of Rosa may seem like a modern-day soap opera, compared to what we argued the research on her contributed to the academic literature: “not only in identifying emigration patterns but also patterns in leasing coal-company housing, in deaths of women, children and miners and in replacement of wives and recruitment of company labor” and “comparative glimpses into transformations in intimacy, inter-gender power, paid labor and home production.” So, please keep this in mind as you read the following.

Rosa was a “white widow,” relying on support from Antonio, who worked in the Monongah mines. Rosa was vulnerable, with their daughter and intermittent support from Monongah. Giuseppe came from a home wealthy enough to provide food. Though married, Giuseppe dominated his wife and parents to continue his flagrant relationship with Rosa until his family refused Rosa’s presence at a family gathering. In a frenzied and irrational response, Giuseppe set fire to an animal stall, which incinerated the house and killed his mother.

Giuseppe escaped but Rosa was jailed for suspicion of conspiracy. The following month, January, 1905, after almost four continuous years of stay in the US, Antonio returned, greeted by shame and confusion, mocked in his plans to return to Monongah with his wife and daughter: Rosa was in jail and pregnant.

Within a few months, Antonio, left for the US with his daughter, Isabella and, in May, Isabella was admitted to the care of the Sisters of Charity in Wheeling, West Virginia. Late the following year, 1906, Rosa, now in West Virginia, took legal action to get support from Antonio and failed. In response, Antonio sought an action not possible in Italy: divorce. Also, he wanted legal custody of his daughter. In March, 1907 Antonio received a divorce and custody of Isabella, nine months before he died in the Monongah explosions. Isabella remained with the Sisters at the convent, where there is no record of her receiving a visit before she died there in 1921, at age 21. However, there is an indication of an unidentified person attempting to contact her after she died and a note that Isabella expressed a wish, unfulfilled, to see her mother before she died. After that, failing to uncover any more information on Rosa, research came to a halt for some months, until we learned Giuseppe changed his cognome and migrated to West Virginia.

Indeed, Giuseppe and Rosa, reunited in West Virginia, raised a family under a different cognome and very different circumstances. Giuseppe, once socially graced in the paese, was no longer a domineering presence; sixteen years older than Rosa, exhausted after years of work in the Grant Town mines, increasingly dependent on the energies and initiatives of Rosa and two sons who entered the mines at about thirteen years of age. He was remembered by two grandsons as taciturn, with little to say; the grandsons, unaware of Giuseppe’s dramatic change in status, attributed this demeanor to poor English and possible undiagnosed effects of black lung. In contrast, Rosa, began her US life in her mid-twenties, no longer in the clutches of a clouded past and freed from the debilitating South Italian economy, as well as customs and traditions for women. Also, Rosa used well her resources, wit, and labor in West Virginia. While burdened with the birth of four boys within thirty months and the deaths of infant twin boys, Rosa was undaunted; even with such hardships, she was renewed by migration. While unaware of their grandmother’s first marriage, their memories of her no way comported with a poor subordinated girl of the paese. She was remembered well and with fondness by her grandsons. Rosa gathered what grew wild, like dandelions, chicory and poke salad and cultivated on their plot of land what could be consumed or sold, including products from an herb garden. She grew poppies for opium – a non-prescription remedy Rosa used in her practice as a midwife. She had a cow, whose surplus milk was sold, and a smokehouse to preserve meats. She crocheted bedspreads and dining-room tablecloths. Of course, Rosa cooked and the grandsons remembered the sound of the horn in their car approaching grandma’s house, a necessary warning during a hairpin turn on nearby Buttermilk Hill – and a signal for Rosa to start boiling water for pasta.

History is distinguished from heritage with a duty to uncover what was, rather than embellish what wasn’t. What was revealed with research on Monongah and the lives of women widowed by its disaster may suggest why this distinction is an important one.