Since June it has been possible for citizens of several European Union countries to travel to Italy following the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, so I decided to venture south from my Rome base to visit and verify the situation at the famous Amalfi Coast.

There were far fewer tourists there than usual, and it was a rare chance to see the popular beauty spot without the crowds that usually overrun this lovely area.

It is worth noting that throughout my trip I was able to attest that the Italian social distancing and other protective measures were being taken very seriously so I felt extremely safe.

It felt strange to roam almost empty streets that, at this time of year, are usually packed full of tourists from all around the world.

If you imagine an Italian seaside holiday, it’s likely that you’re visualizing the Amalfi Coast. The images in your mind would include narrow winding roads encircling a rugged coastline and villages spread out along the steep flanks of the rocky Lattari Mountains that seem to plunge straight into pristine blue water.

The Amalfi Coast has been a favourite summer spot for rich Italians and the international jet set for many decades. Compared to many other resorts favored by tourists, the Coast retains its exclusivity because the areas of accessible coastline are extremely limited and, with the exception of a handful of sandy beaches, located directly in front of Amalfi and a couple of neighboring towns, swimming and sunbathing are restricted to small pebbled beaches and coves. The rich and famous arrive here on boats and yachts and moor them offshore.

Every summer, the Amalfi Coast is the preferred destination for scores of tourists hoping to relax on the beaches and swim in the crystal-clear waters, hikers keen to explore the area’s famous trekking trails and, of course, its delicious food and wine.

Located south of Naples and close to Salerno, reachable between one-and-a-half and two hours by high speed train from Rome, compared to the rest of the country, the Amalfi Coast itself experienced very few cases of the coronavirus during the height of the pandemic. But, given that just like Italy’s famous art cities – Venice, Florence and Rome – it’s an area that relies heavily on tourism, and especially foreign tourists to survive, the aftereffects of Italy’s high numbers of infected and dead, and the ensuing lockdown have been severely felt.

Boarding the train at Rome’s Termini Station, I was immediately aware of the social distancing measures that were being strictly enforced.

Absolutely everyone was wearing a mask and respecting the one-meter rule.

In the station, the temperature of all travelers was taken before they were allowed to enter the platforms.

Throughout the station, a series of stickers on the pavement instructed you where to stand and how to distance.

On the train, signs showed passengers where to sit and instructed them to wear a mask.

When she checked the tickets, the conductor made sure that everyone was wearing a mask.

Passengers wore masks on the SITA buses and Travelmar ferry boats that carry travelers up and down along the coast.

Hotels too are following extra safety precautions and require visitors to follow social distancing rules, wear masks in public areas, and to “check in online,” requiring guests to send passport or ID card details ahead of their arrival so hotel staff won’t need to touch documents.

Hotel rooms and apartments for rent are scrupulously sanitized.

In Amalfi and all the other villages, there were official government posters on display every few meters explaining what the coronavirus is, how to protect yourself from it, and describing the measures in place.

Italian destinations such as Rome, Venice and the Amalfi Coast are usually jam-packed with American tourists from mid-July at least to the end of September.

This time, in Amalfi and the other areas I visited along the coast, there were some tourists, but it was very quiet when compared to usual at the end of July. And not a single American in sight!

As a matter of fact, it was far too peaceful. The narrow streets of Amalfi were uncrowded and mainly populated by locals. There were primarily Italian and some European visitors from several countries including Hungary. Most noticeable was the lack of American voices.

There were no queues for restaurant tables, gelato, in the clothing and souvenir shops or on the beach.

Every store, tiny cafe, and gelato shop was taking the appropriate precautions to serve customers safely and there were a lot of empty chairs and tables everywhere, clearly not only on account of social distancing reasons.

To enter any space open to the public, a mask was required and most tourists and every single shop person was wearing one. Outside the shops, many tourists wore their masks on their wrists while roaming the uncrowded village streets.

Separate entrances and exits to shops, perspex screens between restaurant tables, and floor markings showed that all businesses were making a huge effort to be safe for visitors.

At all private beach clubs, visitors’ temperature was taken before entry was allowed. And again, masks were required in public areas and hand sanitizer was available everywhere. In fact, it seemed as though every few meters, there was a small dispenser of sanitizer.

In Salerno, the port from which the TravelMar ferry boats link various locations along the Amalfi Coast, is a short walk from the train station. The journey to Amalfi takes approximately 30 minutes. The short trip provides an occasion to appreciate the beauty of the Coast with its rugged mountains plunging directly into the sea, miniscule pebbled beaches, and a sequence of small towns or villages located wherever the mountains leave some space between their slopes and the sea, and a series of lemon groves laid out in vertical rows of terraces that are stretched out horizontally along the flanks of the mountains.

Amalfi, the town that gives its name to the coast, is situated at the mouth of the Valle dei Mulini, literally, the Valley of the Mills. It was the first of the Four Maritime Republics of Italy and for a long time had the monopoly of trade with the East. Arriving from the sea, one notices clusters of white houses clinging to the rock. At the center of the main square there is the beautiful Cathedral of St. Andrew, currently undergoing restoration work, with its impressive staircase.

It is impossible to write about Amalfi and not mention its lemons. Hundreds of years before the first tourist ever set foot on the Amalfi Coast, the local population depended on the lemon business to survive.

Although lemons were already known in ancient Roman times, the lemon we know and appreciate today first appeared as a result of the Republic of Amalfi’s trade with the Middle East.

Decades of attempts at cross breeding with local oranges eventually yielded the hybrid first described by Botanist G.B. Ferrari in 1646:

“The nipple is prominent, the rind is rough, pleasantly scented with a sweet taste, the flesh has 8 or 9 segments, the taste is pleasantly sour.”

Initially, the fruit was grown to provide sailors with vitamin C on long sea voyages to avoid scurvy.

Gradually, the lemons grown here were traded across Italy and by the 19th century the cultivation of lemons had become a business that sustained the entire coastal area.

Decades of painstaking work transformed the previously unproductive rural landscape by creating a series of terraces and orchards carved into the fringes of the rocky flanks of the mountains throughout the area that stretches from Positano to Vietri sul Mare.

With the exceptions provided by a handful of fishermen, the production of lemons involved the entire population of the towns scattered along the coast. The men were engaged in the cultivation of the lemons while women were assigned to transporting the fruit from the terraces.

This was no meager feat if one considers that a basket fully loaded with lemons could way up to, and above 50 kilos.

Nowadays, the areas dedicated to the cultivation of lemons consist of several rows of narrow terraces aligned one on top of another, carved into the steep mountain slopes, each one demarcated and held in place by large drystone walls. The terraces are still accessed only by steep staircases, carved into the mountains used by male manual workers who transport baskets full of freshly picked lemons on their shoulders. The staircases and paths that lead from one terrace to another are too narrow and too steep to permit the use of any sort of motor vehicle so teams of mules provide an indispensable means for transporting the lemons from the orchards on the mountains to the villages far below.

The lemon trees flower in May while the harvest is done by hand from February through the month of October.

The remaining months are dedicated to pruning and fixing of the branches, which are bent one by one, wrapped in thick black cloths in order to protect them during the cold season, and secured to an arbour, a shady garden alcove with the sides and roof formed by trees trained over a framework.

Aside from the perfect growing conditions – the volcanic soil, subtropical climate, and plentiful rainfall – the green netting one can see wherever there are lemons growing along the coast plays an important role, holding in the warmth and protecting the fruit from frost and hail, as well as keeping birds out.

In addition to preserving the original colours and perfumes of the Amalfi Coast, the cultivation of lemons protects the land from abandonment and prevents landslides, providing a perfect example of sustainable coexistence between humans and nature.

I’m picked up at Amalfi’s small port by Salvatore Aceto, whose family has been cultivating lemons here for six generations. In a yellow electric golf cart, normally used to transport tourists, we ride up to where the Aceto family’s terraced lemon orchards are stretched out in the Valle dei Mulini.

The area one can consider the Aceto family headquarters – an open-air dining space and a kitchen where Salvatore’s wife Giovanna holds her cooking classes – lies up in hills, barely two kilometers from Amalfi’s city center.

Here, beneath the cover of thickly interwoven vines that allow the light but not the heat to pass, it is quiet, the air is clean and cool and, in the

evening, one can hear the sound of water gushing down the streams that give the valley its name and reference the presence of several water mills that were initially used to make pasta and later transformed into paper mills.

We are met by Salvatore’s father, Luigi nicknamed Gigino, who was born and raised in these lemon groves, where the Aceto family has been

working in the field of lemon growing and transformation, first as tenant farmers, then as landowners since 1825, when Luigi’s great, great,

grandfather, Salvatore, started his activity as a producer and merchant of the precious citrus fruit by purchasing a small piece of land.

Gigino was born in 1934, the eighth of 13 children. Back in the day, Mussolini’s Fascist government encouraged Italians to have as many children as possible, so his parents were rewarded with a special large-family subsidy.

In 1968, thanks to a special low interest 40-year loan from the Italian state, part of an agrarian reform aimed at helping farmers buy their own land, Gigino enlarged the family properties. In time, he was able to further expand its assets, purchasing other pieces of land, the most important one located in the “Valle dei Mulini,” that gives its name to the family brand.

Gigino, who can be said to be 85-years-young, still shows up for work every day on the farm, which produces 50-70 tonnes of lemons a year. He still drives around in a 1960s Fiat 500, which his wife, Rita, an obstetrician, used for several decades to reach her patients, scattered all along the coast.

“Both of my sons work with me in the family business,” Gigino tells me proudly. Salvatore is in charge of running the farm and the Lemon Tours, while Marco runs the production side of the company, making limoncello liqueur, lemon honey and other products from the lemons, which are so sweet you can eat them whole. Marco’s wife works in the family shop close to the main square selling the products to tourists.

The main lemon harvest took place roughly 3 months ago but, in addition to the maintenance of the plants that goes on in one form or another all year long, there still are lemons that must be picked. Gigino and Salvatore take me on a short tour on one of the terraces and Gigino proudly hands me one of the lemons they grow here on the farm. It is almost as big as my hand, an average size, he explains. The lemons can be smaller but also larger.

This particular type of lemon that grows in abundance on the Amalfi coast is known as “Sfusato Amalfitano”. The name “sfusato” comes from the Italian for spindle, “sfuso”, owing to the long-tapered end of this large, knobby fruit that has few seeds and sweet-pulp. The “Sfusato Amalfitano,” is considered a unique variety on account of its quality and organoleptic characteristics and has been awarded “protected geographical indication” status by the EU.

The body responsible for its preservation is the Consortium for the Promotion of the Amalfi Coast Lemon or Consorzio di Tutela del Limone Costa d’Amalfi I.G.P. Salvatore advises me, when buying lemons, lemon liqueur or lemon by-products, to make sure that they have a sticker with the I.G.P. logo, that is an official guarantee that the lemons used were grown in the territory according to the traditional rules of production.

Gigino and Salvatore show me how to pick the lemons. Each one must be individually picked using a pair of sturdy scissors that can cut through the stem. “You can’t pull it off, you have to cut it,” says Gigino, “otherwise you’ll kill the next generation.”

Gigino shows me a plant with what seems to be a strange kind of bud. He handles it very carefully, bending it towards me. “This is next year’s lemon,” he says.

Starting roughly a decade ago, Salvatore has added a series of activities that are linked to the family’s cultivation of lemons; these include “lemon tours”, cooking lessons and food tastings.

The Amalfi Lemon Experience, as the tours are called, are conducted by young, friendly, cheerful, English-speaking staff, and they bring in an important number of visitors. Some tours include a cooking lesson and they all end with a slice of lemon cake and a shot of ice-cold limoncello.

The cooking lessons are conducted by Salvatore’s wife, Giovanna, and they allow participants to discover that the Amalfi lemons are an important ingredient in the cuisine of the Amalfi Coast. Nothing is wasted. The juice, the flesh, its precious yellow peel, and even the leaves are used in the kitchen.

I watch Giovanna prepare special ravioli with fresh ricotta cheese, lemon zest and pepper.

Zest is the rich outermost part of the rind of an orange, lemon, or other citrus fruit, which can be used as flavoring.

On a lemon, zest is the yellow part of the peel (skin) on the outside of a lemon.

The zest is shiny, brightly colored, and textured. The pith is the inner white, fibrous membrane directly below the zest which helps to protect the fruit inside.

Giovanna grates the zest onto the ricotta cheese, adds freshly ground pepper and mixes the ingredients together.

Then she carefully puts a small lump of the mixture on thin strips of pasta, leaving an appropriate space between each small dollop, folds the pasta enclosing the filling within two layers that are pressed together, and then uses a special mold to separate the ravioli.

This year Giovanna has fewer classes than usual so I’m treated all by myself to a special homemade lunch (all of the dishes were freshly made here in the outdoor cooking area), that includes the special lemon-flavored ravioli I watched her make before, eggplant parmigiana style, a caprese salad (mozzarella, tomatoes and basil leaves) and, for dessert, lemon tiramisù, accompanied by a chilled local white wine.

Luigi still gives a hand tending and gathering lemons on the terraces. Climbing up and down the steps every day has allowed him to stay in great physical shape. Basically, all aspects of the lemon cultivation are still carried out by hand just like they’ve been for hundreds of years and the heavy baskets still have to carried by humans down the steep steps and along the narrow trails that run alongside the terraces.

“Here,” says Salvatore, “everything is vertical. Luckily, we have mules and donkeys to help us carry the harvest.”

On account of the challenging nature of the terrain and the hardships associated with the cultivation of lemons on Amalfi’s steep terraces, this particular type of agriculture is known as “heroic agriculture.” In Italy, agriculture on steep terraces like these can also be found on the island of Lampedusa and in the Cinque Terre region, in Liguria, near Genova. Salvatore laughs when I mention “heroic agriculture.”

“We’re not heroes. Just extremely dedicated normal people,” he says with a shrug.

In recent decades, the number of locals depending on the cultivation of lemons to make a living has dropped steadily and the social and economic conditions have changed drastically.

“Until the ’60s and ’70s, the terraces of the Amalfi coast provided a livelihood for entire families,” says Salvatore, “but today, 95 percent of the coast’s economy is based on tourism.”

Young locals aren’t attracted to a job that entails climbing up and down thousands of steps a day, carrying backbreaking lemon-filled baskets weighing up to 60 kilos.

Salvatore says he can understand them. “Who would want a job like this if they can find work as a waiter?”

Like other farmers around here, Salvatore now depends on workers from Ukraine or Romania to take the places left vacant by the locals. They are all strong men and they carry the lemon-filled baskets down the steep flights of stairs on the shoulders. “They do a great job and I couldn’t manage without them.”

Amalfi lemons can’t compete with produce from Argentina, Morocco, Spain or Turkey, where the farmers can use machines and production costs are much lower. As a result, in recent years, many local farmers have given up, abandoning their terraces that have fallen into disarray.

The Aceto family realized that, in order to survive, it was necessary to open up the precious terraces to tourists, encouraging them to visit the lemon groves, taste the fruits, and buy homemade limoncello liqueur.

This year is not a good year. “First of all,” says Salvatore, “The harvest was poor, roughly only 50 percent compared to last year.” But he adds, “Last year it was better than average, so this kind of fluctuation is normal.”

But worst of all, he says, the COVID-19 pandemic delivered a mighty blow, greatly reducing tourism in the area and impacting the lemon business as well.

“The two are inextricably connected,” says Salvatore. “Hotels and restaurants are suffering and so are Bed & Breakfast establishments. The crisis has hit us too because fewer tourists means less sales of our lemons to restaurants, less visitors for the lemon tours and cooking classes, less sales in our store.”

And, while American tourists are missing completely, there are some visitors from European countries and Italians, mainly on the weekends.

“Hotels here are fully booked for the two weeks around Ferragosto, the mid-August Italian holiday, but already starting from August 24th and 25th, there are no more reservations.”

About 30 percent of the farm’s annual output is used by Salvatore’s brother Marco, who is in charge of the family label’s limoncello (a sweet lemon liqueur) production. Ten percent goes to local private clients, 10 percent to restaurants and the rest is distributed in Northern Italy and exported to other European countries.

Salvatore and Gigino take me down to the lab where limoncello is made. The peel of the Sfusato Amalfitano is thick and very fragrant, which makes it excellent for the liqueur. Making it is simple: all it takes is lemon peel, alcohol, sugar, water and time. That’s it.

As a matter of fact, Limoncello (sometimes called “lemoncello”) is made by soaking lemon zests in neutral grain alcohol for a month or more.

The finished product is a bright yellow, thick, sweet dessert cordial with an intense lemon flavor. The secret is to use only the outer peel of the lemon’s skin and not the bitter pith.

Typically, limoncello is heavily sweetened and as a result, a well-made limoncello has a distinctively syrupy mouthfeel – the physical sensation a

food or drink creates in the mouth, including the tongue and the roof of the mouth – with a balanced contrast between the acidic lemon zest and

caramelized sugars, which both deceitfully conceal the somewhat bitter taste of alcohol. Consequently, when well-chilled, limoncello is smooth and very easy to drink and its lemon flavours are satisfyingly delicate.

Here, the lemon zest is peeled by hand. In other companies machines are used to do the same thing. “We prefer to do it this way,” says Salvatore. “We don’t produce as much limoncello as some other businesses.”

If you want to be sure that your purchase is the true product from Amalfi, it must say ‘Amalfi lemon’ on the label.

In addition to being an ideal after-dinner liqueur, made into a spritz with prosecco and a dash of soda, the limoncello Spritz is a perfect summer cocktail, served in bars and cafes all along the coast.

In the afternoon, I go for a walk in the historic center of Amalfi. My destination is Pasticceria Pansa in the Piazza del Duomo, close to the steps of the cathedral. Run by the same family for over 180 years, this café/pastry shop is famous for its sweets, cookies, candied fruit and chocolates, most of them made with Amalfi lemons. This year it’s possible to find a free table outside the Pasticceria or in front of its sister location just across the square.

I notice that the waiters and personnel serving customers in the square or inside the shops are all wearing masks; the same is true for the pastry chefs inside the work area situated behind the main establishment.

“We are taking all possible precautions,” says Nicola Pansa, one of the current owners. The lack of clientele clearly is a problem but “fortunately,” he says, “immediately after the lockdown, before shops were allowed to re-open to the public, we started a system of home delivery. Our regular clients supported us – in fact, we will continue to use home delivery even in the future – and we didn’t have to let go any of our personnel.”

The following morning, I head towards Praiano on a regular SITA bus that travels north along the famous coastal road.

The 50-kilometer-long road known as Strada Statale Amalfitana, SS. 163, built between 1832 to 1850, when the Bourbons ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies that included Naples and all of Southern Italy, connects Sorrento to Amalfi, passing though the 13 towns situated in between. Before the construction of the coastal road, locals reached all the towns via footpaths and mule tracks that still exist and are greatly appreciated by trekking enthusiasts.

Following the natural contour of the coastline, the route is tightly wedged into the rocks and the sea cliffs, consisting of an uninterrupted succession of brief stretches of winding road, tunnels and hairpin turns, that offer spectacular views at the exit of every tunnel or hairpin bend.

In some sections, the road is just wide enough for the contemporary passage of two buses travelling in opposite directions but in many other sectors there is just enough room to allow the passage of a bus and a car. During the summer months, the narrow road is filled with huge tour coaches, local buses, cars and scooters, furiously honking at one another as they fight to access the narrow sections in the vicinity of hairpin turns; consequently, it is virtually impossible for any vehicle to pass another, and all traffic along the coastal road proceeds at a snail’s pace.

But this summer is not like any other. Nowhere is the lack of tourists more visible than along the coastal road: the short bus ride from Amalfi to Praiano that in normal times might have required over an hour to complete, took me barely half an hour.

Shortly after arriving at Praiano’s boutique Hotel Margherita, I was able to have a chat with Margherita Fiorentino who, with her husband, founded the hotel named after her. Usually Margherita holds her cooking courses in the morning, but this year the lack of tourists has led to a temporary suspension of the classes, so I had a chance to talk with her about the good old days.

In 1960, Margherita and her husband Giuseppe moved to New York, where they remained for four years. They owned a delicatessen on the corner of Columbus Avenue and 64th Street. During their stay in New York, they were able to save some money so they returned to Praiano and started the construction of the hotel, transforming the family house.

In July 1965, they also opened a bar-restaurant on the beach at Positano and they called it “Beach Bar.” It was open almost all year round says Margherita. “The Beach Bar was very popular, it was filled with clients, especially Americans, all day long, and every day I worked here until 2 PM and then in Positano until 2 AM in the morning. This allowed us to finish construction of the hotel in 1971. That same year, my daughter Suela was born. I continued working in both places until 1982.”

Back then, Margherita says, “We had a lot of rich visitors including our regulars who would show up every year in September. Especially the movie stars.”

The Amalfi Coast has always had a special relationship with the glamorous world of cinema. From Positano to Amalfi to Ravello, the crown jewels of the coast have been a popular setting for several important American films shot on location.

Additionally, from the Fifties through the Sixties, Cinecittà studios in Rome, nicknamed Hollywood on the Tiber, provided the location for several large American film productions, like “Quo Vadis” (1951),

by Mervyn LeRoy with Robert Taylor, Deborah Kerr and Peter Ustinov; “Roman Holiday” (1953), by William Wyler with Gregory Peck and

Audrey Hepburn; “Ben-Hur” (1959), by William Wyler with Charlton Heston, Stephen Boyd and Jack Hawkins; “Two Weeks in Another Place”

(1962), by Vincente Minnelli, with Kirk Douglas, Edward G. Robinson and Cyd Charisse, so American movie stars would often come down to

the Coast on vacation or to rest and recover after finishing a film.

During the filming on location in Rome of “Cleopatra” (1963), by Joseph

L. Mankiewicz, Elizabeth Taylor and her co-star Richard Burton began a-not-so-secret love affair that provided endless fodder for gossip columnists and tabloids. After divorcing from their respective spouses, the two stars married each other in 1964.

As Eric Kohanik wrote in “ReMind Magazine”, “Over the course of the 14 years that followed, Taylor and Burton would go through a high-profile, power-packed personal relationship filled with twists and turns that included courtship, marriage, divorce, a remarriage and a second divorce.”

In October 1966, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton had just finished shooting Franco Zeffirelli’s “Taming of the Shrew” based on Shakespeare’s play that would be released the following year.

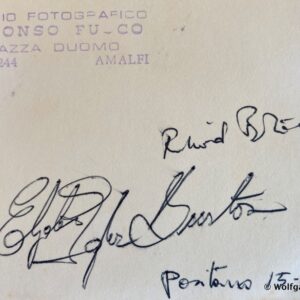

“The couple came to Positano to rest for two weeks,” says Margherita. “They would come to the Beach Bar every night. Liz was always smiling and very nice. She had wonderful purple-green eyes. I’ve never seen eyes like hers before. She liked the photo of my baby son Luca and both she and Richard Burton autographed it on the back.”

And Margherita adds: “They liked all sorts of dishes but she and her husband would mainly drink. A lot. I think she drank so much to keep Burton company.”

“In 1971, I started cooking for our American guests. Many of them were the children of Italian immigrants and they would ask me for dishes that their grandparents used to cook. Since I’d lived in the States,” says Margherita, “I was familiar with the kind of Italian food they liked and the way they prepared the dishes, which wasn’t exactly the same way we did here.”

“My cooking classes are held in our restaurant. It’s called ‘M’ama’ and the name is an abbreviation of a saying from a game lovers play plucking the petals of a daisy. In Italian, ‘M’ama, non m’ama,’ in English, ‘She loves me, she loves me not.’”

Margherita teaches the secrets of Mediterranean cuisine. “One of the main things I teach is the importance of using simple, quality ingredients.” The participants learn how to recreate some traditional dishes that are typical on the Amalfi Coast.

“Most of our clients are American,” adds Margherita. “and we miss them.”

Today, Margherita’s daughter, Suela, runs the hotel. She confirms the fact that this summer there are many fewer guests and no American tourists. “This year,” she says, “95 percent of our guests are Italian and 5 percent are foreigners, mainly Brits, French, Germans and Belgians.” “Last year,” adds Suela, “90 percent of our guests were foreigners, of which approximately 45 percent were Americans.”

Suela believes that there is no use in being pessimistic. “We hope the Americans will return next year and, in the meanwhile, we’ve concentrated on improving the quality of the services we offer at the hotel.”

One cannot make a trip to Praiano without visiting Paolo Sandulli, a 71-year-old artist whose works can be seen in all of the best hotels and in many of the summer villas of very wealthy Italians that are concentrated in the area between Amalfi and Positano.

“As a matter of fact,” says Paolo, “I’ve never had a merchant or an agent in charge of selling my work. You could say that I get my clients through a peculiar word of mouth system. They first see one of my works in a hotel or in someone’s villa, they ask about it and get sent here to me. Literally, all my clients have come to see me and my works in person, at least the first time.” Because then, Paolo explains, they usually order something else from his website or can even commission a new work made-to-order.

Paolo has his studio in the “Torre a Mare,” one several ancient defensive towers sited all along the Amalfi Coast, dating back to Medieval times; ironically, these so-called “Saracen towers” were erected to function as watchtowers and give the local fishermen and their families time to disperse in the mountains whenever there was an incursion of Saracen pirates.

Sandulli’s studio occupies two floors in the crumbling circular watchtower that overlooks Praiano’s pebble beach. His works include paintings of landscapes and local life and terracotta female heads with colourful sea-sponge hairdos. A spiral staircase leads to an assortment of other works upstairs, including paintings. Here, the statue of a bikini-clad woman is suspended upside-down in a glass vase, as though she had been frozen in mid-dive.

The Avellino-born artist is particularly proud of a series of portraits of Praiano’s fishermen, done at first in pen and ink then as a series of terracotta busts. Sandulli wanted to capture the souls of the fishermen who used to drive the bulk of the town’s economy, before tourism became a more prosperous alternative for many families.

“I wanted to commemorate the old world of the sea and preserve the memory of the fishermen, most of whom have died in recent years,” explains Sandulli. “I see my role here as one of cultural protection as well as creation,” adding, “I consider myself a custodian of memories as well as an artist.”

In the afternoon, Andrea Ferraioli, Suela’s husband, and also the president of the Amalfi Coast Tourist Board, drives me to visit the fjord and the town of Furore, where his cousin, wine producer Marisa Cuomo, has her vineyards and the family winery.

We arrive at the so-called fjord of Furore travelling along the coastal road, Strada Statale 163. Taking advantage of the lack of traffic, we’re able to stop for a couple of minutes on the 30 meter high bridge that crosses it, from which I can see the beach and the village located right behind it, clinging to one side of the steep cliffs that enclose it. Every summer, on the first Sunday in July, a stage of the World Championship of Diving from Great Heights is held at this bridge.

The only way to reach the tiny village below, consisting of just a couple of houses perched at the edge of the inlet, is from the sea or on foot using the very long stairway that descends from the bridge all the way to the beach. Furore was once a fishermen’s village. After the industrial revolution, a flour mill and a paper mill were built alongside the torrent Schiato that drains the waters from the Lattari mountains above.

Next, we drive up the mountain to the main site of Furore, also known as “the town that doesn’t exist”, due to its peculiar layout consisting of groups of houses, surrounded by terraced vineyards, scattered along the mountainside.

Here Andrea’s aunt, Marisa Cuomo and her husband Andrea Ferraioli (same name but no relation) own one of the Campania region’s most interesting companies, Cantine Marisa Cuomo. Back in 1980, the year in which the winegrowing estate was established, Andrea and Marisa, benefitting from the precious assistance provided by oenologist Luigi Moio, decided to focus on quality to stand out from the crowd of Italian wine producers, making wines that taste as unique and extraordinary as the Furore coast.

Overlooking the sea, Cantine Marisa Cuomo dominates a section of the Amalfi Coast. There is a vineyard on one side of the road, and the winery where vinification takes place using the most modern techniques, is on the opposite side. Here the wines of Cantine Marisa Cuomo age in a wine cellar dug by hand into the dolomitic-limestone rock: a fascinating, cool and damp cavern lined with French oak barriques.

Marisa’s daughter, Dorotea, takes me for a brief tour of the vineyard located on the side of the road closest to the sea. She shows me that the vines, trained on pergolas creating a green canopy under which the grapes hang, aren’t planted in the ground. “Here on the Amalfi Coast,” she says, “irrigation of vineyards is not permitted,” pointing out that the vines are planted in the vertical rock face just beneath the surface of the road in openings of the drystone wall, built by carefully laying stones one on top of the other, so the vines grow horizontally and vegetables are planted on the ground, mainly potatoes and beans, to enrich the thin layer of soil.

“These vines are 130-years-old. They find all the water and minerals they need to grow between the rocks, and the cover provided by the foliage allows the slow ripening of the grapes and protects them from UV rays, insects and hail.”

“As you can see,” Dorotea points out, showing me several clusters of grapes of different sizes and shades of green, “in this vineyard we are growing three different kinds of grape: Aglianico, Ripoli and Falanghina. Obviously, this complicates the harvest because the different types of grapes must be picked at different times.”

Dorotea points out that here we are 550 meters above the sea so the grapes in this vineyard will be harvested at least 15 days later than those growing in a vineyard further down the mountainside. “Here in Furore,” says Dorotea, “our vineyards are located at different altitudes, starting at 100 meters above the sea and going as high as 750 meters. This means that the maturation and harvest of the grapes growing in the vineyards at the greatest altitudes can take place up to 40 days later than those closest to the sea.”

The grapes benefit from a sunny southern exposure and a unique micro-climate resulting from the combination of ocean currents, mountains and high-pressure systems. The wines of Cantine Marisa Cuomo, 60 percent of which are made up of white wine, are characterized by small yields per hectare and by late harvesting.

Marisa Cuomo makes nine wines, including Furore Bianco, a white wine consisting of 60 percent Falanghina and 40 percent Biancolella, and Furore Rosso, that combines 50 percent Aglianico and 50 percent Piedirosso, also known as Per ‘e Palummo. Cuomo’s top white, the world-famous Furore Bianco Fiorduva, is made from co-fermenting the local Ripoli, Fenile and Ginestra varieties from different Furore vineyards.

It’s easy to understand why wine growing in Furore is called heroic. As is the case with the precious lemons grown along the Amalfi Coast, all work needs to be done by hand by workers who must climb up and down steep stone staircases linking the various terraces. The harvest is carried out of the vineyards by workers and on the backs of donkeys.

As is written on the website of the “Grandwinetour.it, “It is an extreme territory, full of extreme beauty, which naturally means home to extreme wines.”

I ask Andrea Ferraioli to compare the lemon growing business to the wine business.

“There is no match,” he says. “Until the 80s, lemon growing might have been sustainable, but this is no longer true. Salvatore Aceto and other important lemon producers here on the coast manage to survive today because they’ve diversified, and cater to tourists with the Lemon Tours, cooking classes, etc.”

“Winemaking is far more profitable,” says Andrea. “And Marisa has demonstrated that quality is rewarded and that you can sell an award-winning wine for a decent price.”

In addition to Cantine Marisa Cuomo there are 14 other important wine producers within the area of the Amalfi Coast.

The following morning, Anna Canale picks me up in the little port attached to the beach at Praiano and we head in a motorboat to the hotel she manages with her sister Manuela, on the sea front beneath the town of Ravello and hardly more than a stone’s throw from Minori and Amalfi.

The Ravello Art Hotel Marmorata is accommodated inside what used to be a former paper mill next to a waterfall and on top of a small cliff directly overlooking the sea. The rooms, many of which face the sea, are decorated in the so-called “Marine style” as if they were the rooms of an ocean liner.

The building housing the hotel has belonged to the Camera d’Afflitto family for more than 400 years and was used as a paper mill until 1964, when this activity was no longer considered profitable. In the 80s, the current owner, Salvatore and his wife Laura decided to take advantage of the mill’s unique position and converted the industrial building into a modern 4-star hotel. Today, the hotel is managed by their daughters, Anna and Manuela.

The hotel has its own private access to the sea. Umbrellas and deck chairs surround a small pool built into the side of the cliff and the sea itself is only a few steps down a short stairway.

In addition to its charms, the Hotel Marmorata has one special asset shared with no other establishment along the coast: a spacious parking lot located, under a covering of vines, between the hotel and the coastal road.

Like all the other hotels in the area, the Ravello Art Hotel Marmorata has suffered from the lockdown and from the loss of American tourists. Compared to 2019, in the period going from January through August, the hotel has seen a 50 percent drop in the total number of guests. And whereas last year Americans accounted for 33 percent of all guests, so far this year they only account for 3 percent.

After a wonderful lunch on a terrace overlooking the sea, I take the ferry for a short ride back to Salerno where my brief visit to the Amalfi Coast had started.

Looking back at my quick trip what struck me most was the fact that in all of its lovely towns the normally jam-packed streets at this time of year were practically empty. There were fewer boats moored around the harbors and none of the usual traffic jams along the coastal road that links all of the main towns and villages.

Clearly, the main problem for the locals is the lack of visitors, particularly from across the Atlantic. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic means that tourists from the United States – where cases continue to rise – are not being allowed into Europe. Usually, July is the most popular month for American tourists to visit Italy.

According to Italian government figures, 5.6 million Americans visited Italy in 2019. The US is second only to Germany (with 12.1 million and 14.1 percent) with regards to the number of tourists coming to Italy annually, with American tourists accounting for roughly 3 percent of the total.

According to a study published by the Italian financial newspaper, Il Sole 24 Ore, international tourism in Italy is worth an estimated 42 billion euros in total, some 2.8 billion of which comes from US tourists alone.

Among all American tourists who choose to vacation in Europe, 18 percent prefer to visit Italy, the second-most preferred destination after France.

According to the same study by Il Sole 24 Ore, “Among the wealthiest US travelers, Italy is reportedly the most popular European country for ‘affluent empty nesters’ – the wealthy US adults free from family ties.”

“In previous years we had 80 percent foreign tourists, and half of those were from North America,” the head of the local tourist association, Andrea Ferraioli, told me.

Some 13 percent of Italy’s GDP comes from tourism, a key driver of jobs in the country.

According to Giorgio Ghiglione, writing in foreignpolicy.com, “Tourism is a major source of income and has energized a broader economy with a trickle-down effect. Four million Italians are currently working in tourism or tourism-related activities, a significant portion of the country’s overall 23 million workforce.”

In order to accurately emphasize the impact of tourism on the Italian economy and the welfare of its inhabitants, Ghiglione insists: “It’s not that tourism is all that Italy has got. It’s that tourism is what is keeping Italy’s economy afloat. Last year, for instance, Italy’s industrial output shrank by 2.4 percent while tourism grew by 2.8 percent.”

On the Amalfi coast near Naples, this year most of the small family businesses only opened in early June due to Italy’s long lockdown, while the region’s many luxury hotels only opened in July.

Ironically, hotels have received many reservations from tourists from the United States, for the months of September and October, but managers are afraid that unless there is a marked improvement in the situation in America, which is dealing with the world’s largest coronavirus outbreak, Americans still won’t be allowed to travel to Italy.

Although most hotels are lucky to fill a quarter of their rooms during the week, thanks to Italian tourists, many of them manage to reach 80 to 90 percent occupancy during the weekend.

Despite the challenges for those in the industry, the few visitors present on the coast appeared to be enjoying themselves greatly, not having to deal with the usual onslaught of tourists.

In an effort to generate some business, many smaller hotels have slashed their prices but luxury hotels have been reluctant to reduce their rates, in order not to devalue their establishment.

Within the European Union, the largest numbers of tourists are Europeans but Americans, most of whom come to Europe for tourism rather than for business, account for the second highest figures according to European Commission statistics. According to the financial newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore, 85 percent of US travelers visited Italy for leisure purposes in 2018, with the remaining 15 percent visiting for work.

And because Americans have been visiting the Amalfi Coast for decades, many areas depend on the American tourists for survival.

Even if Americans were allowed to travel to Europe later this year, the numbers of visitors would be drastically reduced compared to usual.

It is obvious to all that the effects of this year’s unusually slow summer season will be felt by residents and business owners who rely on making enough money from tourism to see them through the winter.

While I feel lucky to have had a chance to visit this beautiful area of Italy during this special time when there were so few tourists, it was made clear to me that locals desperately need the tourists, especially the Americans, to come back as soon as possible.

The message from the Amalfi Coast to America and American tourists is loud and clear: “We are open for business and waiting for you to return with open arms!”