The recent declaration of mpox as a global health emergency has brought renewed attention to this infectious disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) has raised the highest level of alarm under international health law, signaling the seriousness of the current situation. This comes in response to a surge of cases in Africa, with over 14,000 reported cases and 524 deaths this year, marking a significant increase from the previous year.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stated, “It’s clear that a coordinated international response is essential to stop these outbreaks and save lives.”

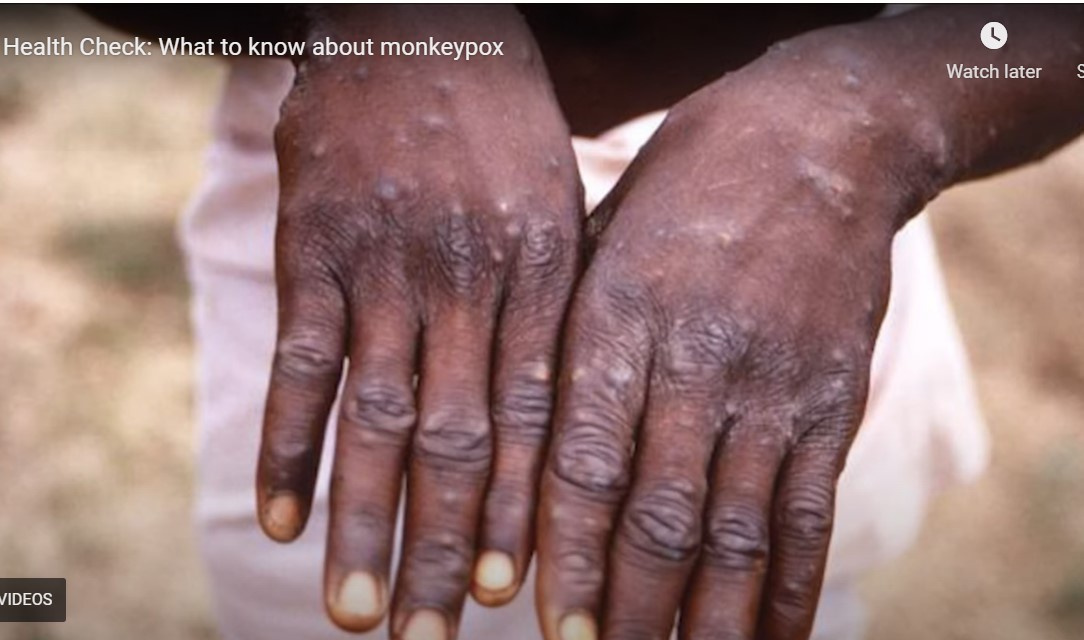

Mpox, previously known as monkeypox, is a rare viral infection similar to smallpox, though typically less severe. It is endemic to parts of central and west Africa but has the potential to spread globally. The disease is caused by the monkeypox virus, part of the Orthopoxvirus genus, and can be transmitted to humans from animals, with human-to-human transmission occurring through close contact with an infected person or contaminated materials.

Contrary to what we might believe from its name, it is not caused by monkeys. Rather, “A number of African rodent species are known to be susceptible to the virus and have been seen to be involved in its transmission.”

The WHO’s decision to declare mpox a global emergency is based on the emergence of a new clade of the virus, clade 1b, which has been reported to be deadlier and more easily transmitted from person to person compared to other clades. This clade has been circulating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and has recently been reported in neighboring countries that had not previously reported mpox cases, including Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda, triggering the action from the WHO.

The threat of an mpox pandemic has been growing in the past two years, but it is not new or even recent. A large outbreak was reported in the US as far back as 2003. In 2022, vaccines and behavior change helped stop the spread when a different strain of mpox spread globally, primarily among men who have sex with men and WHO declared an emergency.

The global community is now facing the challenge of addressing this outbreak effectively. The WHO has developed a regional response plan, requiring initial funding to support surveillance, preparedness, and response activities. Tedros said on Wednesday that WHO had released $1.5 million in contingency funds and plans to release more in the coming days. WHO’s response plan would require an initial $15 million, and the agency plans to appeal to donors for funding.

The comprehensive plan includes understanding and addressing the drivers of these outbreaks, with a focus on tailored and comprehensive responses that put communities at the center of the efforts.

The factors that drive the emerging epidemic are complex and multi-faceted, involving overpopulation, dwindling resources and widespread war and disease. WHO and similar agencies predict that pandemics will become more frequent in the future. The Center for Global Development has advised that, “The next pandemic could come sooner and be deadlier” than the recent Covid-19.

“Virus spillover,” that is, virus jumping species, is a major factor. Specifically, viruses jumping from animals to humans. There is little doubt that the global population will continue to explode (barring some apocalyptic catastrophe). “Human activity drives the emergence of new pathogenic (disease-causing) viruses. As we push back the boundaries of the last wild places on Earth – felling the bush for farms and plantations – viruses from wildlife interact with crops, farm animals and people. Species that evolved separately are now mixing. Global markets allow the free trade of live animals (including their eggs, semen and meat), vegetables, flowers, bulbs and seeds – and viruses come along for the ride.” Experts estimate that 75% of new diseases come from animals: pigs in Europe, monkeys in South America, bats in Asia, and so on.

The declaration of a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) is a call to action for the international community. It emphasizes the need for a coordinated response to prevent further spread and to provide support to affected countries. The WHO and Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are working closely with governments and partners to reinforce measures to curb the spread of mpox.

In Congo, the transmission routes need further study, WHO said. No vaccines are yet available, although efforts are underway to change that and work out who best to target. The agency also appealed to countries with stockpiles to donate shots.