Cesare Lombroso’s theories racialized Southern Italians as primitive evolutionary throwbacks exhibiting a propensity for violence. Even today they cast a dark shadow over Italy’s body politic. A museum dedicated to his research, exhibiting the skulls and other remains of Southern Italians, many of them victims of Italy’s war of unification, was opened in 2009. Now moves are afoot in the Italian parliament and civil society to have the museum closed and for the remains it contains to be given proper burial.

Hundreds of skulls are staring at me through their hollow black orbits. They are arranged in rows and sit neatly on wooden shelves protected by glass paned doors. They are old, but not ancient: about one hundred and twenty years of age. They belonged to people who lived and died in 19th Century Italy. Many display the gapped denture typical of poor working people and peasants. I can guess their age because the surfaces of these skulls are smooth and often pale yellow in color.

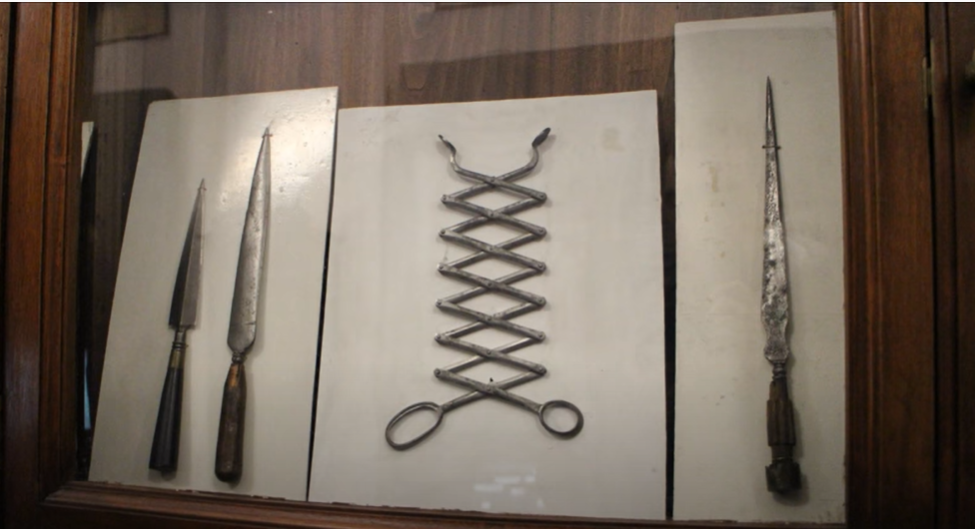

These skulls have been meticulously prepared for display by boiling, scraping and polishing. On the upper rows are approximately one hundred death masks, lifelike colored wax representations of the heads of men and women, with implanted hair, of all ages. Under each is a label: thief, murderer, forger, bandit, prostitute, etc. There are nearly seven hundred skulls, accompanied by almost two hundred pickled brains floating in large glass jars. Some of this material was collected as war trophies, some collected during autopsies, and some stolen from cemeteries.

The location is contemporary Turin, a city well known for its industries, and for being the seat of the kingdom of Savoy whose armies unified Italy in 1861, during the historical era termed the ‘Risorgimento’, or the ‘revival’.

The museum is named after one of the city’s most renowned intellectuals, Cesare Lombroso (1835 – 1909), who founded the discipline of criminal anthropology. Whilst serving the Italian State, first as an army surgeon and subsequently as a university professor, Lombroso developed the theory of criminal atavism by which he argued that all criminals displayed physical characteristics from which one could foretell their deviant behavior. Moreover, Lombroso believed that criminal behavior was facilitated by racial factors. In the US, his research influenced the drafters of immigration laws intended to restrict Italian immigration in the 1920s as well as institutional views of Italian-American organized crime for many years. He also had a lasting influence on Italian criminology.

The skulls, brains and wax death masks displayed in front of me constituted the scientific ‘proofs’ of his ideas. Little matter that his theories were discredited by some of his peers, even during his own lifetime, under the accusation of data manipulation and poor methodology.

When the University of Turin decided to open the Cesare Lombroso Museum of Criminal Anthropology in 2009 its intention was to showcase this thinker’s research and to highlight the history of scientific thought, possibly inspired by the maxim that science also progresses through mistakes. It is true that the Museum points out, in its information to visitors, that Lombroso’s theories were proven to be erroneous.

Nonetheless the question remains: why was this Museum, originally opened to great success in 1906, closed in 1932 under Italy’s Fascist regime, then renovated and reopened to the general public only twelve years ago? What does this reveal about the discursive practices currently shaping Italian society? What does it say about the ideologies that inform the thinking of Italy’s elites?

Historian Susanne Regener believes the first museum’s opening was a political statement. Established not long after Unification, it expressed “symbolically the borders, stigmata, and visionary plans of the contemporary project of making Italy.’’

Could it be that the re-establishment of the Lombroso Museum in 2009 represented a repeat attempt to shore up the crumbling foundations of Italy’s own identity in the face of the twin onslaughts of globalization and mass immigration?

What is remarkable is that very little discussion or debate initially surrounded this museum’s re-establishment, so resonantly situated in the very city of Turin where the whole unification process began. The exception were the Southern separatist movements, also known Neo-Meridionalists and Neo-Bourbons, who sought public recognition for what they saw as historical and ongoing wrongs committed against the Italian South by the Italian State.

All newly established nations need to create their own foundation mythology. For the US this is the Declaration of Independence and the drafting of the Constitution. In Italy it is the idea that all Italians were made equal by unification. On the surface, in the law, this is true. But everyone knows that the unification process ended up making some Italians more ‘Italian’ than others. Nowhere is this more evident than in the treatment reserved for those Italians living in the country’s South.

The aftermath of unification for Southern Italians was often tragic. In the 1860s the brutal Piedmontese military occupation, followed by government incompetence, corruption and heavy taxation, led to the collapse of the Southern Italian economy and to rebellions throughout the South. These were put down in a savage counter insurgency campaign that led to thousands, possibly tens of thousands of deaths. It was during his tours of duty in the Piedmontese army in Southern Italy that Lombroso developed the idea that Southern Italians were racially predisposed to violent and criminal behavior because of their more prominent ‘atavistic’ inclinations or, in other words, evolutionary primitiveness. Included in his definition of criminal behavior he counted rebellious acts of ‘treason’ against the State.

His Social Darwinism could not have come at a better time for the Piedmontese and a worse time for the Southern Italians. It provided a ‘scientific’ bias for the brutality of their army in the repression of banditry, which today we would term insurgency, and in the treatment reserved for Southerners in the Italian penal system in the decades that followed. Lombroso’s ideas also spawned a school of thought that overtly racialized Southerners as inferior to northern Italians.

Even after his ideas were discredited, they strengthened the enduring legacy of anti-Southern stereotypes and prejudices that still run deep under the apparently jocund surface of Italian daily life.

The next time you open an Italian newspaper, consult the pages reserved for crime news. Look for any references to the origins of the presumed offenders. Almost invariably the newspaper will mention whether these people originated in Campania, Sicily, Apulia and, particularly, Calabria. Almost never will they mention whether the presumed culprits were from Lombardy, Piedmont, the Veneto or from any other Northern regions of Italy. Except if these same people had parents or grandparents originating in the South of Italy, in which case these origins are cited once more.

As a nation founded less than two hundred years ago, establishing Italian identity has always been a rather fragile work in progress. Today Italians are suffering from an identity crisis heightened by economic globalization and the arrival of tens of thousands of immigrants from Eastern Europe and Africa. Italian identities have always been much more deeply rooted in regions and provinces, bounded by accents and dialects that can be sometimes traced to single villages, by different cuisines and social practices. It is difficult, indeed almost impossible, for an Italian to identify solely as an Italian.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the rise of new political parties whose platforms reflect identity politics has accentuated these fault lines. As a result, disenfranchised Southerners, not without justification, increasingly believe that Italy’s governments are continuing to represent northern Italian interests at their expense.

Senator Saverio De Bonis’ political career epitomizes the rebirth of Southern Italian consciousness. He is leading the call to close or reform the Lombroso Museum by recognizing that it would be difficult to advocate for policies in support of Southern Italy without bringing unresolved cultural issues to the attention of the general public.

An erstwhile farmer from the largely agricultural Basilicata region of southern Italy, De Bonis was elected to parliament as part of the Five Star Movement in 2018, but later expelled from the party for opposing policies that he believed penalized Southern agriculture. He now is an independent. Recently De Bonis became indignant after hearing a journalist comment positively on the Lombroso Museum in commentary accompanying the latest Giro d’Italia cycling race, during a stage held in the region of Piedmont. After making inquiries, De Bonis was shocked to learn that the remains of so many Southern Italians were still openly displayed there. Together with ‘No Lombroso’ campaign organizers and other intellectuals, he has spearheaded a political push to have the museum closed, or radically reformed, and for the remains be given proper burial.

Many of the people displayed in the museum could still have living relatives, as is the case of Giuseppe Villella, a Calabrian ‘brigand’ whose cranial physiognomy, according to Lombroso, represented the prime proof of his theory of the ‘born delinquent’ incarnating an evolutionary throwback to the apes.

The municipality of Villella’s birthplace, Motta Santa Lucia, sued the Museum for the restitution of the skull in 2012, motivating its claim for “both in the interests of the moral redemption of the city of Motta S. Lucia, because Villella’s skull is not the symbol of a southern inferiority but represents the historical memory of a man who in pre-unitary Italy fought to make justice triumph, and because Villella Giuseppe’s skull represents today the skull of a scandal and its exposure violates the feeling of piety towards the dead.” Although the municipality won its case initially, it subsequently lost it on appeal in 2016 and at the high Court of Cassation in 2019. As a result, Villella’s sawn in half skull is still exhibited in the Museum for the delectation of visitors today.

In May of this year De Bonis submitted a parliamentary question to the Minister of Cultural Heritage and Activities, Dario Franceschini, asking whether it would not be opportune for the Lombroso Museum of Criminal Anthropology to be closed. He followed in June with a parliamentary motion for the Museum to be closed or that it be changed into a ‘real museum of anthropology and ethnography’; that the human remains of Southern Italians be returned to their symbolic region of origin, Naples; that the name Lombroso be removed from street signs throughout Italy.

Interview with De Bonis:

You are a member of the Permanent commission for Agriculture in the Italian Senate. What is your background and what are your political priorities?

“I come from the city of Irsina, in the province of Matera, and I represent the Basilicata Region of Southern Italy in the Senate. Since my election I have always fought for issues related to Southern Italy. I came to Parliament with this background: I am a farmer, I have been a trade unionist, and I seek to defend the rights of producers in the south, who are often forced to choose from limited options and are often discriminated by raw material pricing practices. I have experienced first-hand the problems of doing business in this very difficult area, the South, which is distant from an adequate infrastructure, far from markets and faces uphill battles to place its products. Since entering parliament, I have consistently focused on the problems of the South: from the troubled ILVA steel plant in Taranto, to the situation in Sicily and Basilicata, to illegal waste disposal in southern Campania. Environmental, agricultural and public health issues have been the leitmotif of my political commitment.”

Why did you decide to take up the issue of the Lombroso Museum?

“My interest in the general issue of Northern Italian attitudes towards Southern Italians was sparked when I crossed paths with the historian Pino Aprile, who has written works questioning traditional views of Italy’s unification process–known as the Risorgimento– and its history. Since then, my attention towards wider cultural issues involving the South has grown, as has my political commitment to confronting them.

I became indignant after hearing a journalist accompanying the latest Giro d’Italia cycling race make a positive comment about the Lombroso Museum. Subsequently I was shocked to learn that this Museum still openly displays the remains of many Southern Italians in an undignified manner.

It became clear to me that it would be difficult to advocate for policies in support of Southern Italy without bringing unresolved cultural issues such as these to the attention of the wider public.”

What action did you take?

“Together with my estimable collaborators, I decided to conduct further research into Lombroso with the help of other experts, such as Professor Gangemi of the University of Padua. On the basis of the evidence we collected, and from our online exchange with the public, we realized that the Museum in its current configuration still represents an open wound for many Southern Italians, both within Italy and all over the world. I decided to table a very brief question in the Senate, where I asked the Minister for Culture, Dario Franceschini, whether the government should consider closing this Museum.

What was the Minister’s response?

“Despite the importance of the issue, the Minister took no action. If he had taken the trouble to go to the Museum, would he and his staff still want to support the views that its exhibition is currently projecting? These are views that clash with our image of contemporary Italy, a civilized country, the sixth or the seventh ranking world power. Is it right to keep alive something that can undermine the cultural credibility of the vast heritage of which Italy is so proud in the international arena? If there are some flaws that need to be corrected, or removed, perhaps is it not the case that something should be done?”

What did you do next?

“The Minister of Culture’s response, or lack of it, was somewhat predictable: I did not expect him to respond to the simple parliamentary question that we tabled by closing, modifying or changing the mission of this Museum. That was why we decided to continue in our campaign by tabling a parliamentary motion calling for the closure or the reform of the Museum, because it continues to play a historical, scientific and public role with all its political and social implications.”

What do you specifically argue in your parliamentary motion?

“We argued that the Museum has adopted criteria that are inaccurate, error inducing, and misleading in their messaging, particularly towards young visitors with generic cultural knowledge. In it we focus on the differences between the methods used by Lombroso, which the Museum’s directors still strenuously defend, and more rigorous scientific methods.

We asked whether this state of affairs can still be lawful after so many years, whether it reflects European standards, whether it respects the collective feelings of the many Southerners around the world who consider this Museum to be an open wound that needs to be healed in some manner. This has become our battle. We systematically listed all the errors and horrors that the Museum contains for the benefit of its administrators.”

What do you hope to achieve with the parliamentary motion?

“The advantage of the parliamentary motion compared to the parliamentary question lies in the fact that the Italian Parliament, or at least one branch of it, the Senate, will now have to respond to the motion. We hope this will happen soon. This will trigger a wider public debate, which we intend to incorporate in a future motion accompanied by many signatures. Our initiative will inform many of my colleagues from the South of Italy, not all of whom are fully aware of their own history. We will try to determine whether the Italian Parliament in 2021 can strengthen this process of historical review, without detracting from the role a museum like this should play.

We want to highlight the reality of Lombroso’s research. We want to question the current mission of this museum, advocate for its reform, which includes repositioning its image and reviewing all the display panels, because in their current design, they send an ambiguous message. The museum’s website should also be modified.”

What have been the reactions thus far?

“We have found that when Northern Italian views about Southern Italy are questioned, the former display all kinds of negative reactions. For heaven’s sake, we are not Taliban, as some right-wing groups have accused us of being in their defense of this Museum, which they see as their ideological stronghold. Even city councils such as the one in Turin, have since reversed decisions they took to reform the Museum in 2013, and have opted to maintain this allegedly ‘cultural’ institution in its current form, for purposes that are unknown to us. We suspect that there may be financial motives, or other, rather obscure, reasons. But the real point is whether a museum with an ostensibly scientific mission can still disseminate a message that is racist and ambiguous in its intent. Not only do European legal norms expressly sanction this type of propaganda, but Italian legislation related to museums also prohibits the legitimization of cultural models of this type.”

What do you think of the arguments of those who oppose any change to the Museum?

“Even the scientific community of Lombroso’s day rejected and banned his findings. So why keep alive the memory of a scientist who was already a non-scientist at the time? This is a paradox. There have been many unbalanced people in world history: following the criteria adopted by the Museum’s directors, one could establish a museum for each one of them. The city council of Turin has accused us of putting Lombroso’s research on the same plane as Auschwitz. But of course, it is not the same thing. A more cogent parallel would be to compare this Museum with a hypothetical Dr. Mengele museum in Germany, which no one could ever contemplate.

For its defenders, it is as if the Museum represented the last ideological stronghold of the Northern elites who once reigned over and dominated the country, despite the subsequent course of Italy’s history. Today, for example, 70%-80% of the population of the city of Turin is made up of Southerners, so it is not true that Southerners have not integrated. The Southerners have become cosmopolitan.”

Why is it so important today to change the mission of the Museum?

“Unfortunately, in his day, Lombroso was so successful that he exported his cultural models abroad, even to the United States. It is important for Italy to signal a change, a turning point and to question his importance, because his erroneous theories once misled the whole world. We have a duty to review the mission of this Museum precisely because the scientists of the time sought to do so, because politicians today are doing so, and because the ongoing public debate on the issue, even when it is not very welcome, will continue to do so.”

What will you do next?

“The Minister has not acted as yet. Our motion will encourage him to look more deeply into the matter. As a Member of Parliament our motion has placed the Museum squarely in the political arena. However, as we also specified in the motion, we cannot rule out that the Museum administrators may also have violated the law. Article 14 of the European Convention of Human Rights, which Italy has ratified, prohibits racial and other discrimination. Therefore, there are laws which can anchor possible future initiatives, including in the courts, by the very organizations that are responsible for and legitimated to take them.”