There has always been a certain amount of hysteria in the public debate in Italy, when we need to measure up with the complexities of the European issues.

The case of MES, the European Stability Mechanism, inside of which ( not above, not below, not on the side!) with the Pandemic Crisis Support there are provisions for loans for direct or indirect “health expenses” is a typical school case.

*For each country, a line of credit not to exceed 2% of the PIL. Italy would be entitled to about 37 billion euros, equal to the amount of cuts from the health sector in the last 20 years to assure the containment of the public debt, which today in Europe our partners pose as a condition to offer financial aid: what a joke of fate!

*Negative interest rates for seven-year loans and interest loans equal to zero for ten-year loans: in the case of Italy there is an expectation that it will save five billion euros, funds that could be invested for other priorities, such as schools or infrastructure.

Pro or con: straight answer.

Responsible or irresponsible: straight answer

Pro-Europe or sovereignists: straight answers.

It does not work this way: the ideological Manichaeism does not suit well a weighted evaluation, which on the other hand, should take into consideration diverse variables.

The first and probably most important variable is the political context.

Public opinion, already turned mean by the economic crisis, and that the pandemic has rendered less inclined to benevolent concessions, request from the respective national leaders to extract as much as possible from the deal: for the countries of the South it means requesting solidarity from Europe, economic aid and new (and more flexible) regulations to face and overcome the Covid 19 crisis; for the countries of the North it means not to hand out any gifts “to the countries that steal.” or that, as a best hypothesis, want to take advantage of the pandemic to get assistance and give nothing in return.

The triumph of the stereotype, which has become the compass in the political positioning, is a variable that cannot be avoided if we want to truly account for the nature of the impact of a measure.

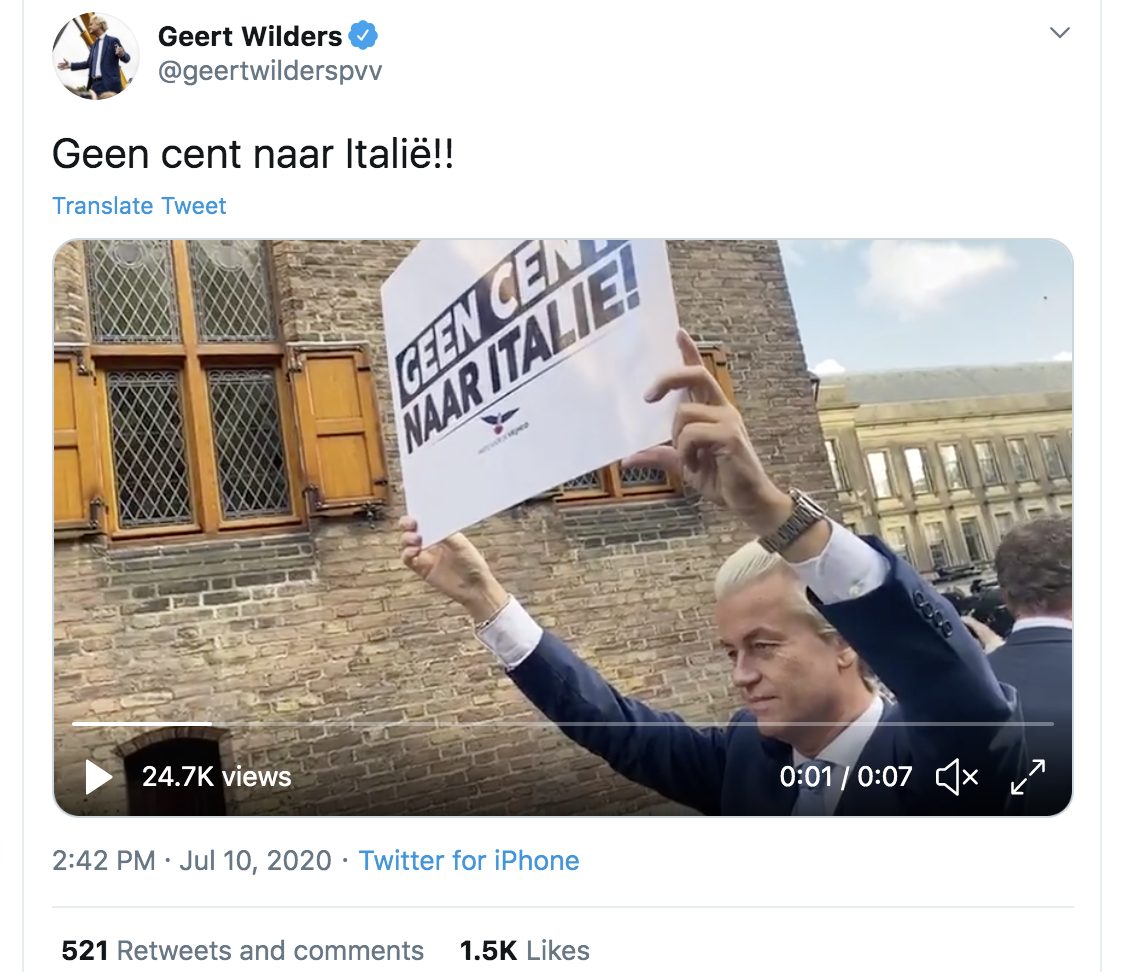

Anybody remembers the little stage scene of the Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte with the employee of a firm that invites him not to give any money to the Italians?

Who remembers the words of the Prime ministers or the Finance Ministers of the so-called “frugal” countries against Italy and the Mediterranean countries?

The rules that are being put together represent the interests of those Countries:

- There is no such thing as free money

- Help and money only under well spelled-out conditions.

And what are these conditions?

They are the so-called structural reforms, already spelled out by the Commission in the context of the specific recommendations country by country published May 20 last, deemed necessary to reduce the public debt: the Italian component is at about 135% of the PIL, way over the 60% foreseen by the Pact of Stability and Growth and the deficit is around 10,5% of the PIL when it should be around 3%.

The debt must be reduced.

Right. But it is the punitive approach that justifies the diffidence about the real good intention

Because “how” the debt is reduced is not as inconsequential as the span of time required to reduce it.

Are we sure that the economic prescriptions of the “European Ants” are effective and sustainable for a “cicada” like Italy?

The Commission has declared that once the crisis is overcome, there will not be a reinforced scrutiny for the Countries that will decide to use the Pandemic Crisis Support of MES.

But what nobody wants to underline is that such declarations are not binding. If tomorrow political conditions–or the actors–should change, these commitments would become disputable and rightly so.

In the absence of a written binding agreement, the conditions that determine the repayment of the debt are those of the MES, a treaty with binding rules and regulations that in the jargon everyone calls the Troika.

For a country like Italy, in a European political context that is highly volatile, the risk of finding the bill collectors at the door with the list of assets to be confiscated or put to use is therefore concrete.

There is no other way we would explain the categorical refusal of Spain and Portugal to MES: it is not so much the minor convenience of the interest rates as the fear of being submitted to a receivership that has pushed these two countries to such clear-cut positions.

The Government is not in an easy situation, neither at the domestic nor at the international level. The home-grown sovereigntists that object in such a sweeping manner to the MES, fearing that it is a Trojan horse for the Troika, are most responsible for the weakening of the negotiating position of Italy, countered by the Euro-enthusiasts, those responsible in the past for having advocated cuts to health expenditures, and according to whom Italy should not refuse the precious opportunity kindly extended by the EU. For these champions of accounting and dogmatic Europeanism, Ms. Merkel’s insistence would be non-repayable and the conditions proposed nonexistent or sacrosanct and sustainable.

The Country could probably avoid resorting to the MES only with a good comprehensive agreement on the multi-annual budget of the UE, on the Recovery Fund (Next Generation EU) and with conditions of having access to its loans and subsidies. The negotiation on this package of interconnected instruments is complex and the credibility of Italy is compromised by the internal weakness of the Government.

What would happen to the markets if Italy, because of its economic characteristics, of the effects of the pandemic and the lack of internal political cohesion, were the only country of the 27 of the UE that would apply for a special line of credit based on the MES arrangement?

What guarantees are there that the appeal to MES would not be interpreted as an infamous brand, the scarlet letter A, the pretext for a speculative attack? And how much – and at what price – could Italy be covered and supported by the European Central Bank?

MES and financial support are in exchange for commitments: this is what is being proposed by the European partners to the countries that find it difficult to overcome the crisis.

The insistence on the need, that can no longer be delayed, to approve structural reforms such as a specific commitment for aid, is so pressing that it emerges everywhere with the same tone in every measure of discussion, starting with the debate on the Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF), the seven-year budget of the European union, framework of the Next Generation EU, the instrument for economic recovery made up of loans and subsidies for a total of 750 billion Euros. And here one must add also the obligation to make available the resources spoken for the green and digital transition.

Everything is beautiful; too bad that the funds available are not sufficient to support to the end an industrial revolution on the continental or macro regional level, and that there are already competitive distortions until now based on north-Europeans political models of development.

Who would cover the social and economic cost of the transformation? In Holland, or in Finland, or Malta they would not have the same impact as in Italy, a great manufacturing country whose productive base is diffused and is constituted by small and medium enterprises, not always with a high innovative value.

Are we really thinking of doing away with an industrial system that is rooted in a peaceful and painless way and is also savings-oriented?

And this is not all. On the morning of July 10 the President of the European Council Charles Michels, in presenting the proposal for a a Multiannual Financial Framework post 2020, explained that the European budget would be financed in part with European taxes, starting with the introduction of the so-called plastic tax.

If this proposal to the Council of Europe of July 17-18, were to pass it would mean that Italy and Spain would have to finance quite abundantly the Recovery Fund from which they would benefit, considering that together with Greece they are the main producers of single-use plastic. And to add insult to injury, the northern countries would instead get some discounts to their contribution to the European budget in recognition of having opened the way to the agreement.

And if to this is added the insistence on reinstating fully, as soon as possible, the rules of the Pact of Stability and Growth, suspended for the time being to allow affected countries to face the pandemic, one understands quite clearly that the political climate is not one of the most indulgent and that the system of rules — connected to them — that is being constructed is not at zero cost for Italy.

A country of saints, poets and navigators is now being expected under a certain amount of pressure, to become as quickly as possible accountants, digitally savvy and eco-friendly.

Are we sure that Italy can make it? Are we sure that this is in its best interest?

If Italy were a normal country the MES, with the imposition of certain conditions, could probably be an opportunity. But it is also true that if Italy were a normal country it would not need to resort to the MES.

If Italy were a normal country it would have more trust and more power to negotiate with its European partners.

And the issue is also this: they do not trust us. And the less the trust, the tougher are, and will be, the conditions to receive help in times of need.

Trust, with the good will of the sovereigntists and the euro-enthusiasts, is not for sale; it must be earned. This is politics, my friend!

Translation by Salvatore Rotella