I wish to address here another one of those “Oh boy!” or “Things that Make You Go Hmmm” scenarios. I shall state at the outset that I am not going to engage in any general discourse about statues: Columbus, Italo Balbo, Rodolfo Graziani, or those yet to exist, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire or the yet-to-be statue of Mother Cabrini. The John D. Calandra Italian American Institute already dealt with some of these issues in the past. On January 31, 2013 we dedicated the evening to a re-consideration of the Graziani monument (“Rehabilitating War Criminals. The Monument to Rodolfo Graziani”); and another program on October 24, 2017 on Italian monuments in the United States (“Monuments, Public Memory, and Group Identity”).

I shall leave that general discussion and any requisite follow-up for another time and to others, for the time being. Instead, I want to address, if ever so briefly, the Indro Montanelli issue, precisely because, to list two reasons, (1) of the dehumanizing behavior that one human being visited upon another, and (2) of the unmitigated arrogance, hubris, and smugness with which Montanelli himself addressed the issue, once in 1969 and again in 2000.

The dehumanization of it all is paramount to human trafficking and all that it pertains. In his 1969 television interview , he spoke about the twelve-year-old bride that he bought (“che ho comprato”). Indeed, he began his account by calling his marriage to a child a “stupidità senza fine,” a phrase more light-hearted than not that was, to boot, accompanied by an enigmatic smile, indeed a grin. He then immediately proceeded to describe the experience with a nonchalance that truly has no equal. Even in response to the Ethiopian-Italian journalist in the audience, who spoke of rape (“violenza carnale”), Montanelli engaged in, to be sure, a type of moral relativism, as he asked if the female journalist wanted to “istruir[lo] con un processo a posteriori” (teach him with a trial after the fact). This type of defense, let’s be honest, is tantamount to what we heard about Nazi soldiers; after all, they “were only following orders.”

In one of his columns for his rubric, La stanza di Montanelli (2 February 2000), he spoke of the issue again with an arrogance similar to that which he had displayed more than 20 years earlier on TV. The column is a response to a letter sent to him by an 18- year-old female whom Montanelli tries to excoriate with his opening paragraph:

La tua domanda è alquanto indiscreta, e se tu fossi una diciottenne dei tempi in cui io ero un venticinquenne, la cestinerei senza esitare. Ma siccome sento dire che le diciottenni di oggi sono in grado di affrontare qualsiasi verità senza nemmeno l’imbarazzo di doversene fingere scandalizzate, eccoti quella mia, anche se probabilmente tornerà a tirarmi addosso — com’è già accaduto — le qualifiche di colonialista, imperialista, e perfino quello di stupratore.

Your question is rather indiscreet, and if you were an 18-year-old girl from the days when I was a 25-year-old, I would trash it without hesitation. But since I hear that today’s eighteen-year-olds are able to face any truth without even the embarrassment of having to pretend to be scandalized, here’s mine, even if it will probably come back to throw at me — as it has already happened — the labels of colonialist, imperialist, and even that of rapist.

Well, no! Given his propensity before 2000 to discuss this issue with such bluster and braggadocio (he did so in the interim during an interview with Enzo Biagi [1982]; ), the young woman’s question is anything but “indiscreet”; au contraire, she asks him about a previous article of his in which he spoke of his “’storia’ vissuta … con una ‘faccetta nera’” (“lived” experience … with a “little black face”). His response, as anyone who knows Italian immediately understands, reeks, at the very least, of sarcasm. He then goes on to play the victim by complaining that he was accused of being a “colonialista, imperialista, e perfino quello di stupratore” (colonialist, imperialist, and even rapist). Well, he seems to have left out a fourth accusation, human trafficker. Yes, anyone who engages in “buying” another human being engages in human trafficking, defined by the United States Department of Homeland Security as “the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act”.

“Un processo a posteriori?” Well, Montanelli is long gone, and we are left with his own words — scripta manent — of the history of his own behavior in this case — facta valent —were we to opine on the matter. Further still, in so doing, we might be accused of running the risk of looking at history through today’s lens. I, in turn, might concede such a notion, if ever so temporarily, were the distance in time significant; i.e., centuries-old, and I underscore the plural here. But it is not. We are dealing with an issue that took place in the 1930s, and through technology of print and visual media we are now privy to Montanelli’s own words; indeed, those on video are accompanied by tone and gestures, those accoutrements of articulation that contribute to the viewer’s realization of meaning and intent of the speaker.

I was indeed surprised by three attempts to exonerate — Dare we say acquit? — Indro Montanelli by some current-day thinkers. The first two statements by two individuals here I find to be highly problematic, to say the least: 1) On 11 June, 2020, in an opinion piece for Italy’s highly respected Corriere della Sera, journalist Beppe Severgnini wrote that “[i]f an isolated episode were enough to disqualify a life, not a single statue would remain standing. Only those of the saints, and not all of them.” Well, in theory, there may be some truth to this. However, as the thinkers that we are — cogitators to echo the late eighteenth-century dictum — are we not able, indeed, do we not wish, to distinguish the significance of the severity of one act vis-à-vis another? For instance, to be a card-carrying Fascist in 1924 was one thing, but to be an integral part of the mechanism of a regime that made people disappear, as in the case of Giacomo Matteotti is another. (I ask my reader to dispense for the moment of the blurred lines of specificities, as we might be apt to condemn both on an equal level.) Let us not gloss over the fact that this apparently unwarranted, “isolated incident” to which Severgnini alludes involved Montanelli’s “buying” an Ethiopian 12-year-old girl as his “wife.”

So, when I read Severgnini’s comment, I thought, as I quote myself: Now, let me get this straight. Montanelli did nothing of exception save to engage in dehumanizing, racist, sexually violent, and pedophilic behavior. This is the “isolated incident” of which Severgnini speaks! Really? Well, talk about “Things that Make You Go Hmmm,” to cite once more the hit disco song of 1990! But Severgnini is not alone in his quest to keep Montanelli mounted on his perch, forever immortalized in his own public space at the public’s expense in the city of Milan. “È figlio del suo tempo,” Marco Travaglio tells us during an episode of the TV program Accordi&Disaccordi. Following that logic, then, do we also accept the notion that “del suo tempo” were other historical phenomena such as the Holocaust and Slavery? Mine is not a rhetorical question; it asks where do we draw the line, when do we decide that “history” is not a forgiving rationale. If there is no statute of limitations, for example, on murder and other crimes, how is it that “[g]iudicare i fenomeni storici con gli occhi di qualche decennio dopo non ha alcun senso” (judging historical phenomena through the eyes of a few decades later makes no sense), as Travaglio is quoted on the above-cited website? Finally, another member of this choir is the head of the Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d’Italia (National Association of Italian Partisans), Roberto Cenati, in stating the following: “without that man, today we would have Nazis everywhere.” Really? There were no other “giornalisti-partigiani” or others post-quem running around?

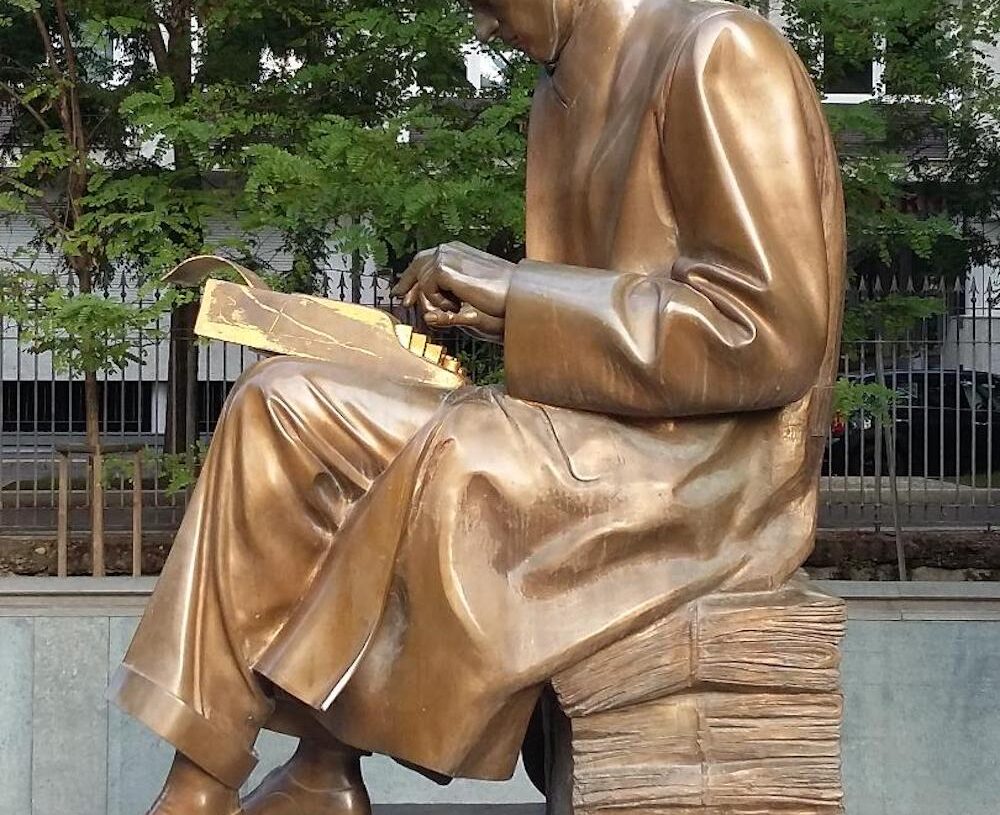

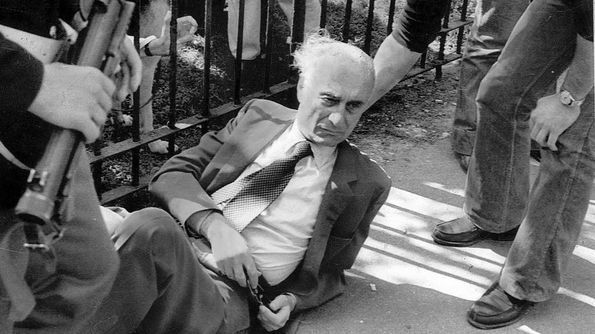

Indro Montanelli was not the only victim of kneecapping by the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades). During that same period Emilio Rossi, the then director of TG1, Italy’s premiere news channel, was attacked. Also wounded in a similar affront was Vittorio Bruno, deputy editor of the Genova daily Secolo XIX. Montanelli, so it seems, happened to be the more conservative and better known of the numerous journalists wounded and/or assassinated during the anni di piombo (Years of Lead); his years of public exposure both in print and on television, as well as his right-wing political leaning, surely contributed to why he was attacked. The irony, in any event, is that he became the idol for a park and statue whereas the other two I mention here, one the news director for Italy’s State Channel 1, did not. Why? Well, the reasons are many, the discussion of which is more suitable for another time and another venue.

The third piece I found problematic is among the three published on this site, La Voce di New York, “Non fare di ogni statua un fascio-razzista: Colombo non rappresenta i valori di Rizzo” (Not Every Statue is Fascist or Racist: Columbus Does Not Share Rizzo’s Values) by Stefano Luconi. While there are numerous debatable issues with any article of this type — to begin with, which statues should remain and which should be taken down — I shall concentrate on that which I find related to a significant degree to the Montanelli controversy. In his first four paragraphs Luconi speaks to the racial strife we currently see around us and the statues. He decries those monuments that are clearly racist in nature, in honor of those individuals who are celebrated for their,

strenua difesa dello schiavismo da parte della società del Sud. Non a caso, molte di queste statue non vennero erette subito dopo la conclusione della guerra civile, bensì nel successivo periodo del consolidamento della segregazione razziale, in special modo all’inizio del Novecento, quasi a voler minacciare dai loro piedistalli gli afroamericani…

for their strenuous defense of slavery on the part of the Southern society. It is no accident that many of these statues were not erected immediately after the conclusion of the Civil War, but in the successive period of the consolidation of racial segregation, and especially at the beginning of the Twentieth Century, almost as if they were meant as a threat to African-Americans.

Luconi then goes on to defend the Columbus statues as an expression of celebration on the part of Italian Americans in order to “onorare lo scopritore dell’America” (to honor the discoverer of America) and, at the same time, to underscore their own legitimacy in the United States since, especially during the period ending the nineteenth century when the Columbus Statue in New York City was erected, “immigrati sbarcati dall’Italia erano considerati indesiderabili e inassimilabili in una società protestante e di ascendenza anglosassone a causa della loro origine mediterranea e della prevalente devozione cattolica” (immigrants from Italy were considered undesirable and inadmissible in a protestant society of Anglo-Saxon origin because of their Mediterranean origin and predominantly Catholic devotion). Okay, so I shall, for argument’s sake, accept the complexities that some might see with regard to the Columbus controversy, especially for the New York city Columbus statue in Columbus Circle. (Again, I remind my reader at this juncture that the Columbus controversy is not the intention of this specific writing.)

With regard to Montanelli, this is where I find Luconi’s piece problematic. As I assume a good number of people might agree, Luconi concurs with many that the statue of Frank Rizzo should be removed; more than his tenure as mayor of Philadelphia, Rizzo’s notoriety originates in his “pugno di ferro contro le organizzazioni degli afroamericani e per le violazioni dei diritti civili dei loro membri negli anni in cui fu il police commissioner della città” (iron fist against African- American organizations, and for the violations of the civil rights of their members in the years in which he was police commissioner of the city). Or, equally unwarranted was the attack he ordered on “una manifestazione pacifica di studenti afroamericani” (a peaceful demonstration of African-American students) fifteen of whom were hospitalized. These actions, according to Luconi, place the monument to Rizzo among those that “rientra[no] a buon diritto tra quelli da rimuovere” (should rightly be among those that must be removed).

The passage from a condemnation of Rizzo for his racist behavior to reverence of Indro Montanelli, whose statue — regardless, and to his own admission, that he was, among other things, a “colonialist,” “imperialist,” “rapist,” and, my word, racist — supposedly — “onora la libertà d’informazione e chi ha avuto il coraggio di alimentarla anche durante i cupi anni di piombo della storia italiana” (honors freedom of information and those who have had the courage to support it even during the dark “Years of Lead” of Italian history), is a gigantic step in rhetoric, to be sure. And I make this assertion of an overwrought argument precisely because of what Luconi himself states as preface to his rationale. His previous two sentences are:

La colpa imputata al giornalista? Essersi vantato di aver acquistato una schiava sessuale minorenne mentre combatteva con le truppe italiane nella guerra fascista di conquista dell’Etiopia nel 1935. Il monumento, però, non intende glorificare lo sfruttamento sessuale delle africane, né il colonialismo italiano. Sorge nel luogo dove Montanelli fu gambizzato dal gruppo terroristico delle Brigate Rosse il 2 giugno 1977…

What is the journalist accused of? To have boasted of having bought a sex slave, a minor, while he was fighting with the Italian troops in the conquest of Ethiopia in 1935. The monument, however, does not intend to glorify the sexual exploitation of African women, nor Italian colonialism. It was erected in the same place where Montanelli was kneecapped by the Red Brigades on June 2, 1977…

The upshot, then, is that, as horrid an act as it is, being kneecapped by the Red Brigades for your conservative writings overshadows the harm that Montanelli befell on Ethiopians in his human trafficking of a minor while being part of a colonialist and sexist regime. Personally, I’d rather see his statue replaced by one dedicated to Walter Tobagi, a journalist targeted and eventually killed on May 28, 1980 by the terrorist group Brigade XXVIII March. (I know, many cities have already honored Tobagi’s memory.)

Severgnini, Travaglio, Cenati, and Luconi himself eschew the evaluation of past events and/or behavior through the lens of today. Indeed, Luconi tells us such phenomena should undergo a “metro di valutazione morale coevo” (coeval moral measure of evaluation). As I mentioned earlier, we might indeed attempt to do so with events and activities of centuries ago, though the extremity of said phenomena and those individuals involved just might cancel out the validity of a “coeval moral measure of evaluation.”

In Montanelli’s case, I am hard-pressed not to moralize history — as Filippo Barberis, a member of the Partito Democratico, to boot, decries doing — in this case especially. While we’re here, we might indeed moralize such opinions about accepting such logic that condones Montanelli’s behavior by the very fact that such grievous harm to another human being, a child, is overshadowed because his conservatism provoked egregious unwarranted violence on him by an extremist group. In this case, the kneecapping that befell Montanelli does not cancel out his own nefarious behavior of human trafficking of a 12-year-old girl. In a certain sense, this forma mentis almost trivializes such past actions; for Montanelli is the poster boy for all four of the above- mentioned miscreant acts! This is not a statue in discussion, this is a human being who violated in various ways another human being, someone who was physically smaller and had not yet reached the age of reason.

In the Montanelli case we are not dealing with any subtle, hermeneutic phenomenon of difference that an able observer of society (journalist or historian) should not overlook and cannot comprehend. Since the vicious murder of George Floyd and Rayshard Brooks in the United States we have initiated a discussion on whiteness and, more specifically, white privilege. Those of us who are not Black, those of us who are not of African origin (specifically, in the U.S. and in Italy), we truly cannot viscerally comprehend what it means to live on the other side of whiteness. This was eminently clear in the case of Montanelli, as we saw in the videos and in his column; he could not see himself as the privileged white, northern Italian that he was. Unless we struggle to recognize our own white privilege, which means questioning our own “moral measure of evaluation,” we shall fall into that trap, run the risk, of seeing things always at a distance and through a semiotic lens of gender and racial privilege, which, while so doing, we do not recognize.