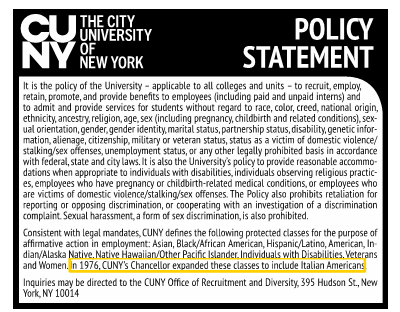

The announcement below appears on a regular basis (annually at the very least) in the NY Times and is to include Italian Americans, a group designated a “protected class” back in 1976. It appeared this Sunday (February 27, 2022) in the section, “Sunday Review,” page 6:

As you can see from the ad’s last line, “In 1976, CUNY’s Chancellor expanded these classes to include Italian Americans.” The ad indeed begins with the statement “It is the policy of the University … to admit and provide services for students without regard to race, color, creed, national origin, ethnicity, ancestry, religion, age, sex…” While the University continues to provide services for Italian-American students (some financed by the Calandra Institute over the past four decades), the one service it does not provide with any consistency or structure is curricular, especially at the graduate level.

That said, of the many issues we can raise with regard to curriculum, one is the lack of graduate studies in Italian-American (read, also, Italian Diaspora) studies within the entire system of The City University of New York (the exception is the existence of four MA courses at Queens College). The good news is that we have a new administration at Queens College and a new administration at the Graduate School and University Center (a.k.a., Grad Center). Before the change in these two administrations, attempts to create an MA certificate were highly discouraged on the one hand, and the inclusion of Italian-American studies at the Graduate Center, on the other hand, was outrightly rejected. In one case we had to explain the difference between Italian Diaspora studies (i.e., the study of the history and culture of immigrants and their progeny outside of Italy) and Italian Studies as we know it (i.e., the study of culture within Italy).

“Testardi” that we are, we shall continue this campaign for a variety of reasons, most important: (1) Italian-American studies in its various modalities uncovers the significance and indelible impact of Italian immigrants and their progeny on the socio-political and cultural fabric of the United States, from the 17th century to today. (2) The disabusing of a mistaken narrative that Italian immigration to the U.S. consisted of a monolithic group of illiterate, poverty-stricken individuals. Was economics a primary reason for many? Of course, no one doubts as much. But some who wish to lead a national conversation on Italians in the U.S. seem to have very little to no knowledge of the cultural and political classes that emigrated as well to the U.S. from Italy, that began in the 17th century and continues today. Such misstatements, instead, fly in the face of historical fact. (3) Notwithstanding the violence that was directed toward Italian immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th century, we need to be sure to reposition such atrocities within the greater scheme of barbarous violence against other racial and ethnic groups as well. (4) While it is true that supercilious micro-aggressions against Italian Americans still exist (some, indeed, perpetuated by Italian Americans themselves, both consciously and unconsciously) we need to calibrate those as well with regard to other racial and ethnic groups.

In the end, we need to be sure that anyone interested in the propagation of Italian-American history and culture is fully informed of what they speak. We cannot state that our history begins in 1891 with the lynching of Italians in New Orleans, something I have dealt with in a forthcoming opinion piece in the Journal of Religion and Society. Our history begins in 1635 with the arrival of Pietro Cesare Alberti and continues from that point on with the likes of William Paca, Filippo Mazzei, and Carlo Bellini in the 18th century, to name a few others, and so on. In order to bridge such a knowledge gap both from within and, as well, beyond the Italian-American population, structured programs that train professionals are the necessary remedy. Such MA and doctoral programs exist for most other racial and ethnic groups in most universities around the country. Some of these programs have funding from their respective communities. At The City University of New York, such programs do not exist in any conspicuous manner.

Giovanni Schiavo, whom we might consider the founding voice of Italian-American studies, believed in those who would engage in the “[p]ublication of books by serious students, scholars, that is, showing the contributions of Americans of Italian extraction to American’s greatness, not only economic but also moral—especially moral” (3). He then continued with the following:

“I am convinced that there are in America today numerous young men and women of Italian origin who are proud of their heritage, not in the sense of those hoodlums who scream about Italian power, or ‘Italian is beautiful’ and similar imbecilities, but in the sense of awareness of one’s hereditary values. This can be done, provided one is willing to spend years and years digging and digging, without expectation of any reward, except the feeling of doing some good.” (3)

What Schiavo clearly references here is the building of an intellectual class of Italian Americans on Italian Americans, those who are truly committed to the enterprise of research and subsequent propagation of the results of such scholarly undertakings. Such intellectual activity is possible through advanced study in the field—i.e., doctoral programs—as well as through the existence of a think tank that, further still, examines all of the major issues that concern Italian Americans (or, as Schiavo states, Americans of Italian extraction).

New York City has one of the largest populations of those of Italian extraction outside of Italy, third only to Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Sãu Paolo, Brazil, the city with the largest Italian population outside Italy, approximately 9.9 million Brazilians of Italian ancestry live in Sãu Paulo according to the website “About Sãu Paulo.” Thus, given not only New York City’s Italian population of approximately 800,000, but the fact that the greater New York metropolitan area has more than 2.6 million Italian Americans, what better place for the first doctoral program in Italian-American and/or Italian Diaspora studies than our own The City University of New York? Rhetorical question, to be sure.

And so, I close with the reference to the title of Primo Levi’s most famous novel, which comes from the millennia-old statement by Hillel the Elder, and which, for me, is the only question left for us to ask: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? If not now, when?”

Works Cited

“About Sãu Paulo.” https://www.aboutsaopaulo.com/culture/italian/#:~:text=Today%2C%20there%20are%20nearly%20300%2C000,Italian%20community%20outside%20of%20Italy.

Schiavo, Giovanni. 1976. The Italians in America Before the Revolution. Dallas: The Vigo Press.

Tamburri, Anthony Julian. 2022. “Observations on Why Promoters of Italian American Culture Need to Know More: The Italian/American Experience of Religion.” Journal of Religion and Society. http://moses.creighton.edu