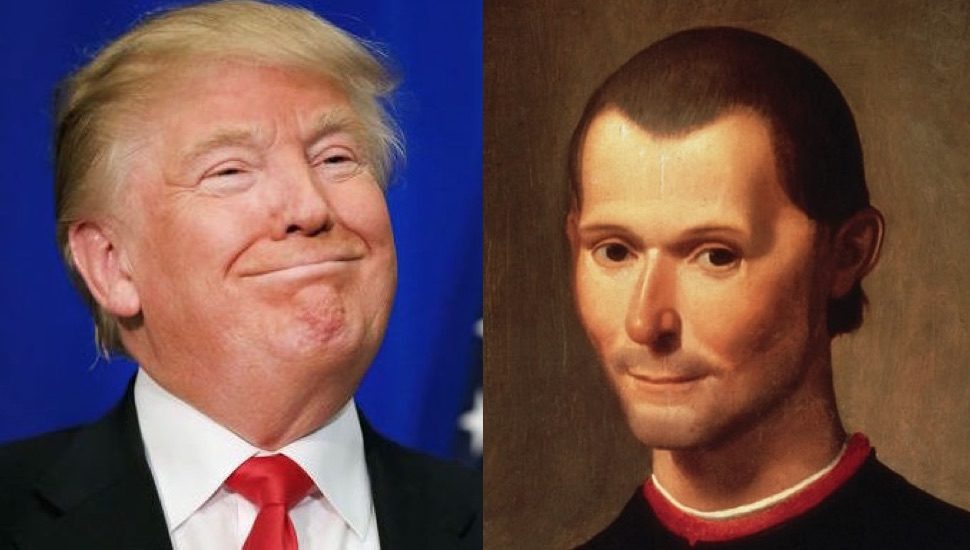

One year ago, after Trump was elected but before he took office, David Ignatius, one of the Washington Post’s most prestigious columnists, wrote an article with a provocative title: Donald Trump is the American Machiavelli.

I doubt he would write the same thing today using the same title. But if – paradoxically – he were to submit the article as a final paper for my course on Niccolò Machiavelli at New York University, I would have no choice but to fail him for totally missing the essence of what good ol’ Nick deems a good political leader.

Especially in light of the revelations in Fire and the Fury, the new best-selling book by right-wing journalist Michael Wolff that is making the White House tremble – it has become ever more clear that Trump has neither the clarity of judgment, the depth of analysis, the political intuition, nor the sublime use of language of the Florentine Secretary.

For 20 years, I have taught courses on Machiavelli for New York University students, and each time I am amazed by the fascination that, after five centuries, the Florentine Secretary continues to exert on this crowd of young women and men coming from all over the world, with their knee-ripped jeans and their eyes permanently glued to their electronic gadget screens. They sign up for my course for the most varied of reasons: some are fans of Tupac Shakur, the maudit rapper that was gunned down in 1996 and that released his last album under ‘Makaveli,’ the stage name he gave himself after reading The Prince in the prison library. Others are fans of the video game Assassin’s Creed, in which Machiavelli appears as an advisor to the protagonist, Ezio, offering him valuable advice to help him kill his enemies. The majority of them, however, attend my lessons attracted by the notoriety of the Florentine bad boy that revolutionized political philosophy with the ambition of turning it into a science.

The objective of my course is, more modestly, to dispel the negative myths that – above all, in the Anglo-Saxon world – have contributed to the adjective ‘Machiavellian’ as a synonym for shrewd, duplicitous, or dishonest. As I tell my students, I am not Niccolò’s court-appointed defense attorney – he does not need one – but it is my duty to make them understand that, because of an ironic twist of fate for an anticlerical agnostic such as himself, Machiavelli was the first victim of the religious wars that began right after his death. For the Protestants, he was the precursor to the Jesuit manipulations in the European courts and the inspiration behind Catherine de’ Medici, who was blamed as the real instigator of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre (which took place about 40 years after poor Niccolò’s death…). For Catholics, he was the precursor to the radical criticism of papal and clergy corruption that was one of the strongest arguments behind the seemingly unstoppable Protestant wave. This strange destiny made it so that Machiavelli was judged in all of Europe, first on the basis of his critics’ writings, and only afterwards on what he himself actually wrote.

It is exactly for this reason that I implore my students not to fall into the temptation of throwing themselves into making simplistic comparisons with today’s political leaders, only conceding one exception, that of Richard Nixon’s failed Machiavellianism. The 37th President regularly quoted Machiavelli and apparently always had a copy of The Prince handy.

Reflecting these past days on the scary revelations of Wolff’s regarding the Trump administration and his brilliant definition of the ‘executive disorder’ that dominates it, I could not resist falling into the same temptation from which I try to salvage my students, and now here I am comparing President Trump’s leadership with Machiavelli’s requirements for a successful political leader.

Machiavelli admonishes the prince to use the utmost caution in selecting his advisors, and Trump has already fired about a half-dozen of them, one of which had to be escorted out of the White House by the secret service. Almost all of them have revolted against him, just like the horrid Steve Bannon, perhaps Wolff’s main inspiration and source. Machiavelli recommends to the prince that he avoid flatterers, whereas Trump loves to surround himself exclusively with people that praise him incessantly and without criticism.

Machiavelli recommends to the prince that he be feared more than loved, but warns him about the danger of being hated, whereas Trump seems not to care about the hatred that some of his measures and statements have earned him from whole segments of the population. Machiavelli polished every sentence of his, just like a precious, no-frills jewel: his sublime prose was a reflection of the clarity of his thought. Trump’s tweets do not achieve the level of linguistic competence that one would expect from a third grader in the USA.

With all due respect to the Washington Post, and ignoring any claims to moral high ground, we can certainly say that Trump continues to reveal himself to be the opposite of the ideal leader outlined by Machiavelli. Perhaps some of his friends could suggest to him that he carefully read Machiavelli’s complete works, but I believe that it is already too late now and, given Trump’s attention span, I doubt he would go beyond the first 140 characters — spaces included, obviously.

Translated by Emmelina De Feo