There are New York hotels that we will always remember and New York hotels that we should never be allowed to forget. The latter served a higher purpose in history; their mere existence was considered a threat for some and a safe haven for others.

In 2017, when Beyoncé won the Grammys, celebrations exploded all over the city. After the show she checked in at the Plaza Hotel only to be told they could not find her reservation and she had to leave. It made news all over the world, as it had happened a month earlier to John Legend who, after his sold-out concert at Madison Square Garden, could not check in at the St. Regis. I still remember the scandal. Do you? If you are not confused by now, you should be, since these events never happened.

However, it is enough to go back a few decades to Bessie Smith, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, and Louis Armstrong to witness that Black stars as well as any Black travelers, until 1966, even right here in New York, could not stay in most hotels because they had a “Whites only” policy.

In the South the infamous Jim Crow laws enforced local segregation in public establishments and in the so-called “Sundown Towns”; if you were Black you risked being arrested, beaten or even killed for traveling after sunset.

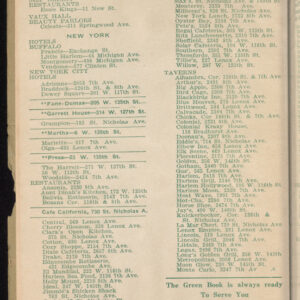

In 1936, a travel guide called the “The Green Book” was published to provide advice on safe hotels and restaurants for Black travelers. In the 1937 edition, even in progressive New York City, only twelve hotels were mentioned as “Negro friendly,” and they were mostly located in Harlem.

From the 1880s to the late 1910s, the Black population of New York City was strongly rooted in what was then called “Little Africa,” stretching from the Lower East Side to the West Village.

Many more Black newcomers escaping the brutality of the Jim Crow South migrated to the Village until a large new wave of poor Italian immigrants settled in the same area, which would be later renamed “Little Italy”.

The Black community was gradually forced to move northwest into the Tenderloin, a poor neighborhood plagued with prostitution, disease and crime that stretched up from 24th Street to 42nd Street on the West Side.

However, just north of 42nd Street, a large Black middle-class community was thriving around Long Acre Square (now Times Square) after theaters and nightlife had moved up from Union Square.In 1900, a Black businessman called Jimmy Marshall opened the very first respectable hotel on 127 West 53rd Street, called The Marshall Hotel. The Marshall soon became the main hangout place for both White and Black actors, artists and musicians. Apparently, it was on the stage of the Marshall Hotel that music evolved from Ragtime to modern pre-Jazz, attracting the praise of the Prince of Prussia who ended up at the Marshall while visiting New York.

However, “sinful race-mixing” attracted the attention of White moral enforcers who noticed that “white females frequent the place, with Negroes, and it is also visited by white people while slumming and sightseeing, triggering a “concerned” White committee to hire a private Investigator that reported “a Negro woman…caressing a drunken white man” and a “degenerate White woman on very familiar terms with a colored entertainer.” The Marshall Hotel closed in 1913.

Meanwhile the demolition of an entire Black neighborhood in the Tenderloin in 1910 to make room for the construction of Pennsylvania Station forced once again, the Black population to move further uptown to Harlem. Harlem was built with beautiful rows of brownstones, theaters and large boulevards, making it an ideal location for a growing White middle-class who wanted to escape midtown but when it failed to attract Whites, developers started selling to the Black community, ironically making it the Black capital of America.

In 1910 only 10% of Harlem was Black versus 90% White, by 1940 with the Great Migration, the numbers had reversed. In the 20s and 30s you had to travel uptown to Harlem to enjoy New York nightlife and the Harlem Renaissance at the Cotton Club, the Savoy Ballroom, Minton’s Playhouse, the Apollo Theater and the Alhambra, where Billy Holiday was once a waitress.

With the Marshall Hotel gone, there few options were left for Black travelers who looking for a place to spend the night until Edward H. Wilson bought a falling down hotel at the corner of West 145th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem and in 1920 renamed it the Olga Hotel. It was the first hotel in Harlem with a Black clientele.

The Olga was featured in the “The Green Book” and immediately became the place to stay for Black businessmen and entertainers including Louis Armstrong, “the Empress of Blues” Bessie Smith, and the baseball star Satchel Paige. The Harlem Renaissance however, did not survive the Great Depression and racial enmity, nor did the Olga Hotel which closed in the 1940s.

Imagine Louis Armstrong, Josephine Baker or Billie Holiday performing at the elegant Waldorf-Astoria for a White-only crowd, revered until right after the curtain came down, when they could neither dine nor sleep in the Waldorf or any other hotel. Instead, they had to head uptown to Harlem to the Braddock Hotel on 126th Street and 8th Avenue or go from “White” Waldorf-Astoria in midtown to the Black “Waldorf of Harlem”: the Hotel Theresa.

The beautiful and stately art deco Hotel Theresa with its splendid white ceramic tiles, known as the “Waldorf of Harlem,” opened in 1913 on 125th Street and 7th Avenue (then called Great Black Way) as a White-only hotel and it was not until 1940 that the manager Walter Scott, hired Black staff and opened it to a Black clientele. It changed America as it wasn’t just the hotel where people that made history stayed, but rather the hotel where history itself was made.

It was where Malcom X created the Organization of Afro-American Unity, where the March on Washington movement was planned, and where Dr. King addressed a large crowd in front of the hotel. World famous Black boxer Joe Lewis also stayed and celebrated his victory at the Hotel Theresa after winning against the German Max Schmeling in 1938.

But don’t forget that while Max Schmeling, who was seen as fighting for Nazi Germany, could stay in any hotel he pleased, American Black hero Joe Lewis, in his own country, was only allowed in the black-owned Hotel Theresa.

Harlem nightlife burst forth at the bars of the Theresa and the Braddock hotels, as much as the Apollo Theater or at Connie’s Inn, where Louis Armstrong played with Fats Waller. All of Black America including Dinah Washington, Nat King Cole, Josephine Baker as well as writer James Baldwin, athlete Joe Lewis and politicians like Adam Clayton Powell, stayed at the Hotel Theresa. In 1960 the Hotel Theresa once again made news all over the world.

During the opening of the United Nations Fidel Castro, who had just taken power in Cuba after toppling Dictator Fulgencio Batista, checked in with his large delegation at the Shelburne Hotel in midtown. Outraged by the demand for full cash payment, he checked out and following the suggestion of Malcom X, he moved his entire delegation to the Hotel Theresa.

He then had Egyptian president Nasser, Indian PM Nehru and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who was meeting Castro in person for the first time, travel to Harlem to meet with him. Castro also raised the uncomfortable reality of discrimination and civil rights in the US with Malcom X. That same year JFK held a rally at the Hotel Theresa, along with Eleanor Roosevelt, and declared “behind the fact of Castro coming to this hotel and Khrushchev coming to Castro… I am delighted to come to Harlem…..”.

But as the poet Langston Hughes asked: “What happens to a dream deferred?….maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode”?

The Braddock bar was incredibly popular and so close to the Apollo Theater that Billy Holiday could almost walk with her drink from the bar right onto its stage.

However, in the city, Blacks were allowed to work or perform in theaters, restaurants or hotels but they could not use their facilities as clients; while in Harlem, White shop owners allowed Blacks to shop but they would not hire them as employees. Worsening racial tensions exploded in 1943 in the lobby of the Braddock Hotel when a White police officer shot a Black soldier who was trying to protect his mother and another woman, “guilty” of having asked for a room change, who was being arrested for “disorderly conduct.”

A rumor had started that the soldier was dead and riots quickly spread through a Harlem tired of racism and police brutality. Protesters also targeted White-owned businesses for the first time, using the slogan “Don’t buy where you cannot work.” The city overreacted by sending 6,000 police officers and 8,000 troops to subdue the protesters.

The struggle and perseverance of these Black hotel owners and the dignity and resilience of its clients opened the doors of every hotel in America to the Black Excellence of Beyoncé and every Black person. However we should keep up with the song, “Ain’t Gonna Let No Body Turn Me Round” because the fight for civil rights is still going on.