Italy, 1930-1960. A country divided before it was even really united. The Italian population was fragmented, turned out by the war, slave of a regime. It was desperately seeking freedom, it was desperately looking for its own identity. At that time Italy needed to be real, needed to look in the face the desecration of its beauty perpetuated by strangers’ hands and ultimately by the Italians themselves. It was first chaos, then war, then misery, then triumph, then rebuild, then rebirth.

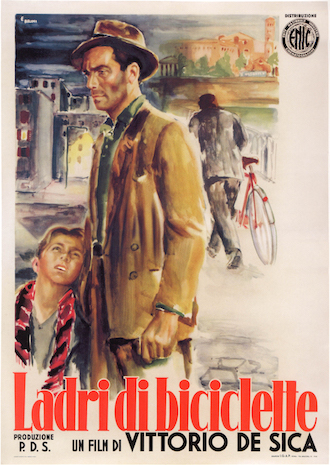

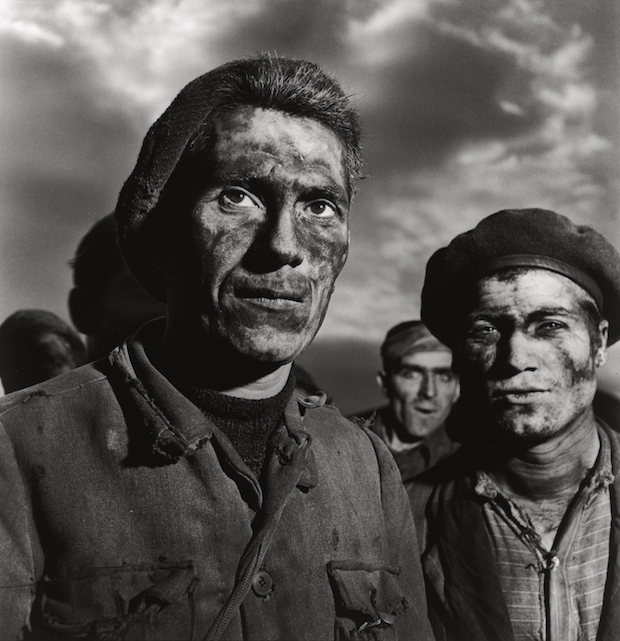

Artists didn’t have time for fairy tales but they certainly felt an urgency of telling tales, of reporting the brutality of that catastrophe through the faces of their protagonists. This urgency for realism would eventually end up producing one of the strongest and most recognizable Italian aesthetics, which is the neorealism. The world, and the United States in particular, has been always fascinated by the bittersweet beauty of the images of Italy during that time, fiercely depicted by the lens of cinema in masterpieces such as Ossessione by Luchino Visconti, Rome Open City by Roberto Rossellini or Bicycle Thieves by Vittorio De Sica, to name a few. What people are less familiar with, is that neorealism was a choral, transversal aesthetics that didn’t interest just cinema, but also literature, with authors likeGiovanni Verga or Luigi Pirandello, and photography.

The ADMIRA-ble Journey of Enrica Viganò

Are you familiar with the names of photographers Cesare Barzacchi, Sante Vittorio Malli or Mario De Biasi? Probably not, and the reason being it is still lost in the mists of Italian art history. And here it comes, breaking through that mist, Enrica Viganò, journalist, art critic and independent art curator who in 1997 founded Admira in Milan, an agency specialized in the organization of photographic events. Viganò’s passion for photography and the neorealism pushed her into a journey of rediscovering those missing snapshots of history.

Art critic, journalist and independent curator, Enrica Viganò

And today we can finally appreciate that evocative realism, chronicled and forever framed in the exhibition NeoRealismo: The New Image in Italy, 1932–1960. This monumental and unprecedented exhibit features some 175 images by over 60 Italian photographers. After conquering Europe, the exhibit is now displayed at the Grey Art Gallery of NYU and at the NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò until December 8th. Jointly, the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York hosts the commercial part of the exhibition.

And if that was not proof enough of the success of Vigano’s project, the master of American cinema Martin Scorsese wrote a foreword to Enrica Vigano’s photographic book that complements the exhibition, underlying the relevance of this project. It is quite the flattering acknowledgment if we consider that it comes from someone who considers himself a son of the neorealism aesthetic in cinematography. Also, The METjust bought 93 of the pieces which will be exposed in the museum’s permanent collection.

“The aesthetic canons of neorealism penetrated in the United States even before they did in Italy,” said Stefano Albertini, Director of the NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò addressing the exhibition. “The Americans found a different sense to those movies. They looked at them as a way to respect and pay homage to the thousands of American soldiers who died in Europe. It seems like the American public was just waiting to see this exhibition because it really complements the imaginary of those movies of the neorealism that here in the U.S. are so well appreciated and studied.”

Come discover more about the exhibition in this exclusive interview with Enrica Viganò.

I often like to start my interview with a question: what is that you do, produce and create in your life? Because actually, that is what poetry literally means in Ancient Greek – to do, to produce, to create. So ultimately I’m asking you, what is your poetry Enrica?

“Well, what I created is Admira, a studio that organizes photographic cultural events in Milan since 1997. We just came upon our 21ist anniversary, and we couldn’t celebrate in a better way than with the success of this exhibition in New York. Photography has always been my passion, I worked for 5 years for ll Diaframma, the first ever Italian private gallery dedicated to photography. My personal mission is to divulge the photographic language in all of its layers, specifically today that photography is abused and somehow banalized by the social media”.

Tell us more about the journey of this exhibition.

“Neorealism is of course known everywhere in the world thank to the great Italian cinema. But neorealism was a choral phenomenon that comprised all of the art expressions. The photography of the neorealism has always been complementary to the cinema, it is a sort of brotherhood. In the publicationCinema Nuovo, founded in 1952 with the purpose to keep the debate around the theme of realism alive among the intellectuals of that time, photographers would be hired to publish the so-called photo-documentaries. Photographers would come up with plots, ideas, and storylines that they would put down in a series of photos that would eventually inspire new movies”.

What is the perception of the American public of the photography of the neorealism?

“The perception doesn’t exist. Meaning that for the Americans the neorealism photography it is something that is absolutely brand new, they thought neorealism was just about the movies. That’s the reason why I asked Martin Scorsese to write the introduction to my volume. I knew about his famous movie My Voyage to Italy (Il mio viaggio in Italia), where he collected all of the movies of the neorealism that inspired him. I knew how much he loves this aesthetic”.

And this aesthetic entered the collective imagination with a force that was and still is unprecedented. No other Italian movie genre has been that vividly emblazoned in people’s minds. Why do you think that?

“A phenomenon like the neorealism happened because of that specific historical moment that Italy was living. Neorealism took inspiration from the fascist era communication tools, from photography to cinema, radios, and the publications that Mussolini would utilize for his propaganda in 1922-1943. Right after the war, 1945-1948, neorealism became a common language, a language of the collectivity, of a nation that was still looking for its unity, identity, and democratization. That was before Italian society would be polarized and split into the left and right wing, before the elections that saw the Christian Democracy party against the Communist party. As Italian writer Italo Calvino said, neorealism wasn’t an artistic movement, it was a collectivity of different voices, different Italies, that from the north to the south felt the urgency of understanding each other. A unifying phenomenon like that in Italy it is not to be found ever since”.

On a personal level, what of the lyricism of the neorealism inspires and moves you so much?

“Besides the fact that technically these photographs are stunning, I feel personally moved by the stories behind the men depicted in the pictures. These little stories of men have created our great history. These are stories of people who after the war rolled up their sleeves and fought against misery, poverty, destruction with their will and creativity, and they rebuilt our country. It is so moving to think about that”.

We live today in the so-called “Selfie Era”. Where does photography stands in this regard? It is still a form of realism, a new form of neorealism, or is it perhaps hyper-realism?

“I believe that the “Selfie Era” and the abuse of photography operated by social media, it has anything to do with realism, neorealism or hyper-realism. I just see vanity and a constant celebration of oneself. But I don’t want to demonize the social media at all, it is true that they can become a vehicle of information and a platform of visibility for artists that probably we would have never known about because maybe they live in a remote angle of the world”.

Speaking of visibility, now that your exhibition conquered New York, what’s next?

“The fact that we were able to enter the USA art market with these photographs it is an important stepping stone because if you are recognized here, of course, you are going to be recognized in the rest of the world. Also the fact that The Met acquired 93 of the pieces it is the ultimate consecration. Not only, but 11 of these photos are also shown in The Met’s new acquisitions space, which is a first, usually they expose a diversified body of pieces, this time they chose to go along with the theme of Italian photography of after the war period. I’m honored and flattered by this success, also because I did everything by myself. In Italy, the Ministry of Culture is not interested at all in helping and funding our artists when they try to be recognized abroad, especially when it comes to photography. That’s also why my profession to me it is a real life’s mission”.

And after having witnessed the fire, the determination and the passion in Enrica’s eyes while she speaks about her work, I can’t help but think of how ADMIRAble her mission is.

Article first published on The Digital Poet.