Last Christmas holiday season, one of the most popular gifts for Americans was a spit tube, a plastic test tube with an airtight closure that is part of a kit that one can purchase online or at a pharmacy. A couple of months after you mail off your saliva in a pretty, pre-paid package, you receive your genetic sequence—a snapshot of your DNA that unveils your geneology, and even the genetic diseases of which you may be at a potential risk of having, including Alzheimer and Parkinson’s Disease. The cost of these analyses, once prohibitive, has decreased considerably in the last few years to under $100, and even less if you order multiple kits or take advantage of family discount offers.

The major DNA-testing companies (the most popular being 23andme.com, ancestry.com and myheritage.com) have begun offering this service at more and more competitive prices – and they are winning big business, especially after the Food and Drug Administration gave them the authorization to give patients the results of their medical genetic testing directly without the mediation of medical personnel. But it seems that Americans are more interested in learning where they come from than in discovering a potential genetic predisposition to degenerative diseases. A few scientists still raise their eyebrows when they hear talk of this supermarket-style gene mapping, and the same companies that offer these services write – in very fine print – that test results should be viewed more recreationally than scientifically. However, an investigative TV news program that sent the saliva of two identical twins to the three major companies (obviously after changing their names and addresses), discovered that the test results provided by the companies were the same, proving their undeniable reliability.

The scientists who work for these companies note in the informative introductory pages of the DNA testing kit that genetic testing results avoid using words such as “race” and “ethnicity” since, as it is well known, they are not based in science; instead, they claim to be capable of detecting, with good approximation, the geographic origin of ancestors and the historical period in which a certain genetic strain was introduced into a family. But why are these tests so popular here? For starters, only the remaining descendants of Native Americans could proudly say that their history begins on these lands. The “American aristocrats,” those who trace their origins back to the pilgrims who arrived on the Mayflower, make up an even smaller group of people. Everyone else who lives in this country is, to some degree, mixed, but the exact ingredients of that mixture had been largely unknown.

And when I say “mixed,” I mean it in the American way, not in the way it is meant in Italy. My friend, Ruth Ben-Ghiat – distinguished historian of Fascism and CNN columnist – laughs when she thinks about the reaction Italians have when she tells them her mother is Scottish and her father is a Yemeni Jew. Without fail, they respond, “I’m also mixed – my father is from Florence and my mother is from Prato”.

For many white Americans, however, these test results can be a source of trauma. Thanks to genetic testing, many, especially in the South, have discovered that a significant share of their genes come from Africa—a shameful reality kept secret in family conversations. They are probably descendants of the thousands of female slaves that were raped by their owners and that involuntarily became mothers to a line of unrecorded “mixed” sons and daughters. Trying to shed light on some family secrets, many discover facts that are oftentimes disturbing (e.g. your real father not being the man you have always known, instead being his best friend who obviously had an affair with your mother). Others, like adopted children, hope to discover the identities (and origins) of their biological parents.

For many white Americans, however, these test results can be a source of trauma. Thanks to genetic testing, many, especially in the South, have discovered that a significant share of their genes come from Africa—a shameful reality kept secret in family conversations. They are probably descendants of the thousands of female slaves that were raped by their owners and that involuntarily became mothers to a line of unrecorded “mixed” sons and daughters. Trying to shed light on some family secrets, many discover facts that are oftentimes disturbing (e.g. your real father not being the man you have always known, instead being his best friend who obviously had an affair with your mother). Others, like adopted children, hope to discover the identities (and origins) of their biological parents.

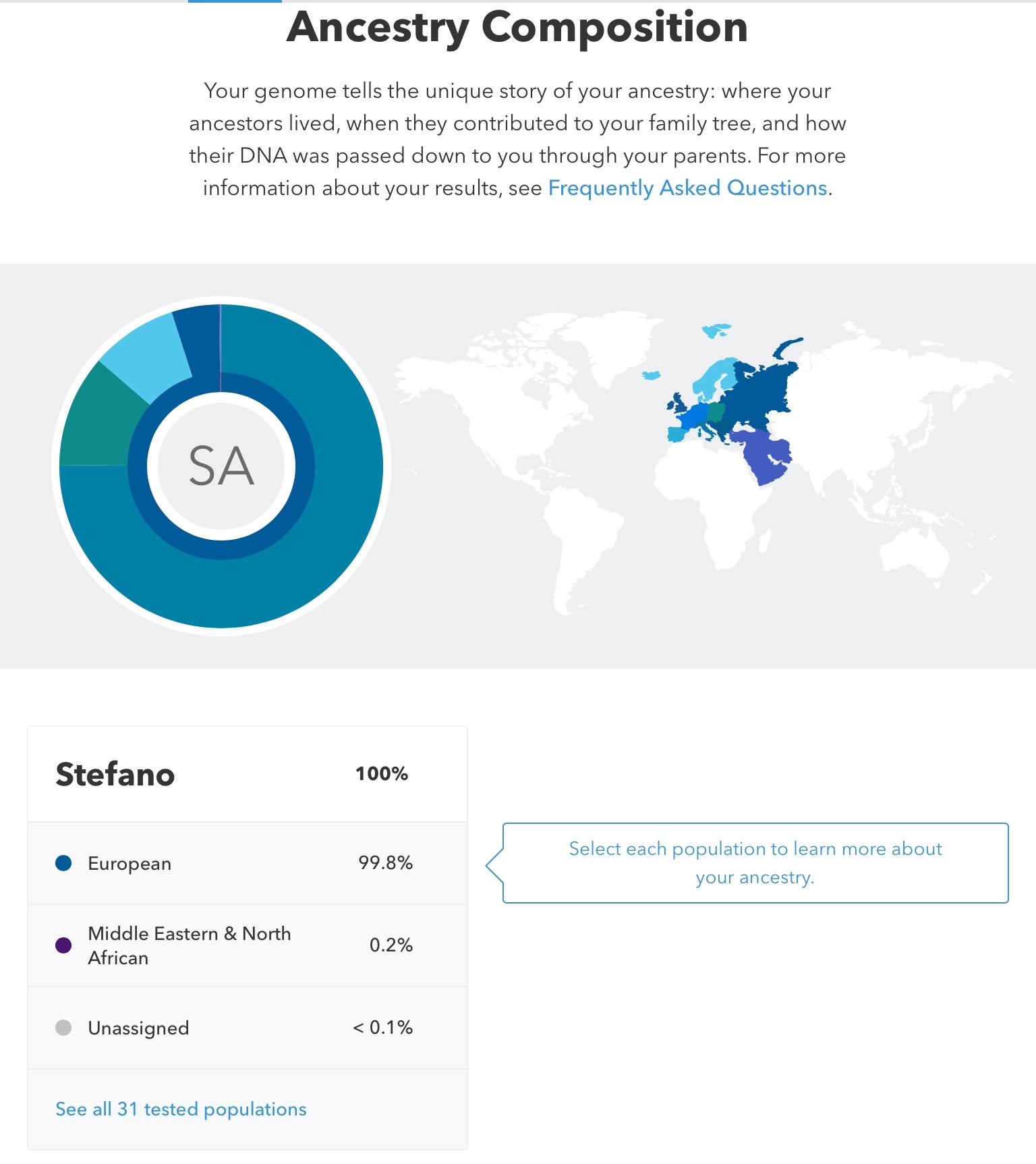

So what did I discover when I received that awaited email from 23andme? Nothing surprising, really – European origin: 99.8%. I held back a yawn and proceeded to read my pretty and easy-to-read charts – even for someone like me who is completely useless when it comes to math and statistics (I do not need a DNA test to confirm that I lack that gene) – and found confirmation of my family history. The end of the 1800s to the beginning of the 1900s is when the Ashkenazi Jewish component was introduced into my family (12.8% of my DNA). It must have been my great-grandfather, Attilio, my beloved grandmother Gemma’s father. We know that he was an artillery cadet officer and that he died of typhus during the grand maneuvers in Palermo before he was to go into battle against the hated Austrians, as he desired. He died without seeing his baby girl. The Franco-English component arrived between the 1700s and 1800s, which is also unsurprising – my great-grandmother Bianca’s last name was Chapuis. The Iberian component was introduced during the same period: was one of my great-grandfather Attilio’s grandfathers perhaps Sephardic? And could that “Balkan” part perhaps have originated from my other beloved grandmother Luigina’s Hungarian ancestors? We know that Hungary is not in the Balkans, but even 23andme concedes to its customers that it is not easy to split the genetic map even between Poland and Russia.

But the three things that I continue to ponder since receiving the results are not the confirmed details of my own family history, but rather the much broader simple truths that I knew even before taking my DNA test.

a) All human beings have in common more than 97% of their gene pool. The difference in origin is only the residual 3%;

b) All genetic strains (all of them) – come from Africa, even those of racists, white supremacists and members of the KKK;

c) If you scratch a bit under the surface, you will discover that even if your mom is from Bozzolo and your dad is from Canneto sull’Oglio (nine miles apart) you are much more “mixed” than what you have ever thought.

Translation by Emmelina De Feo