Carnal Knowledge – The Films of Pier Paolo Pasolini (February 17th – March 12th), is about to bring to an end an exhaustive retrospective in celebration of the centennial of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s birth. It was organized in partnership with Cinecittà at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures – a museum designed by Renzo Piano, the brilliant architect from Genoa, and inaugurated last September 30th in L.A.

The main theater, “David Geffen”–with its one thousand seats upholstered in red fabric, a state-of-the-art Dolby audio system, as well as an elegant and innovative red safety curtain – is the proper setting for the premiere of the complete film series of a visceral filmmaker like Pasolini.

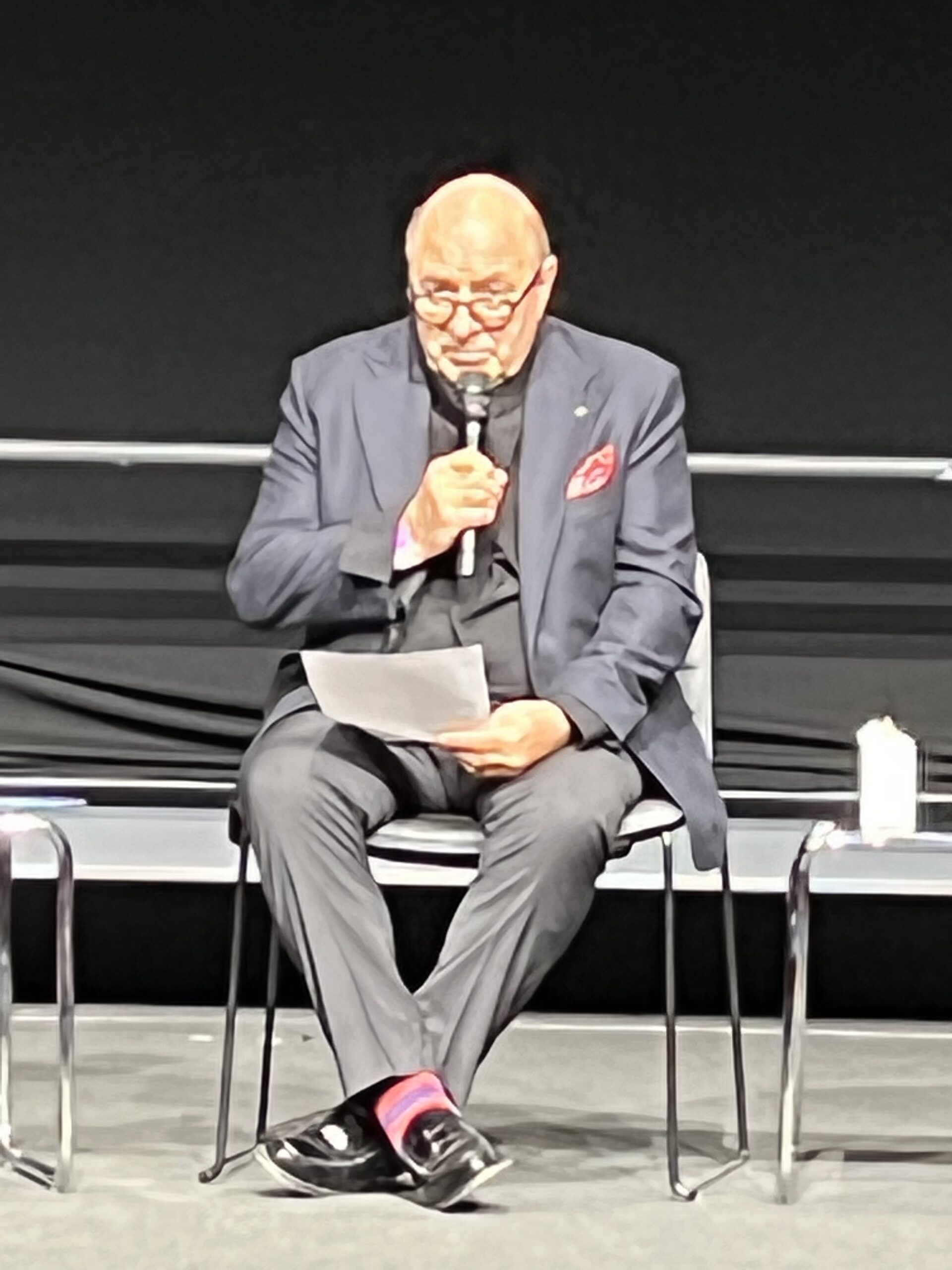

A juicy taste of the evening lies in the precious recollections by Dante Ferretti – three-time Oscar winning production designer native of Macerata, Italy – who whets the audience’s appetite in anticipation of the screening of Accattone (1961), the directorial debut by Pasolini, digitally restored in 4K DCP by Cinecittà and Cineteca di Bologna.

In the early 1960s, while still attending the Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma, Dante was introduced by an acquaintance to renowned production designer, Luigi Scaccianoce, who would soon become Pasolini’s frequent collaborator.

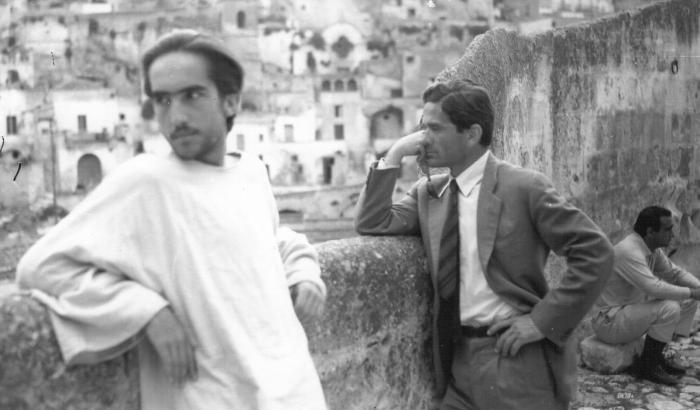

“Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) was the first movie I collaborated on as assistant production designer. Since Scaccianoce was busy with other movies, I had to prove myself to carry out the director’s vision. After doing location scouting in Palestine, Pasolini had opted to shoot the film in Southern Italy, mainly in the Sassi di Matera. The task to recreate the right atmosphere, that could transport spectators back to the holy places of Christianity, has been far from easy. Pasolini taught me a lot.”

Ferretti showed himself to be up for the task and got hired again as assistant production designer for the following surreal and poetic movie, The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966), a witty blend of Marxist ideology and Franciscan pauperism, in which the tragicomic “mask” of Totò and the sparkling physicality of Ninetto Davoli tower over the barren and alienating landscape of Rome’s suburbs.

As soon as Dante mentions his next collaboration on Pasolini’s first color feature film, Oedipus Rex (1967) –an adaptation of Sophocles’ tragedy of the same name embedded with Freudian references – the moderator and retrospective’s curator, Bernardo Rondeau, highlights the return of Franco Citti as its leading actor, after his successful debut in Accattone.

The guest denies the obvious with a simple, “No,” thus triggering the audience’s thunderous laughter. “I am sorry, but it’s been over fifty years and I don’t remember very well,” he quickly adds.

“Scaccianoce, a line producer, a couple of other crew members, and I traveled to Morocco to do some location scouting. We visited Casablanca first, then Marrakesh, and lastly, Ouarzazate. The last consisted of a single street, lined with a bazar and a tiny French-style hotel on one side, a saloon on the other, and a hospital at the very end of it. After lunch, Scaccianoce told us he needed to go back to Italy to work on another movie and said goodbye to us. A few days later, Pasolini joined us in the Moroccan village and asked me about Luigi. I explained to him what had happened and he observed, ‘Better this way.’ Once again, willing or not, I had to take charge of the situation. After agreeing on Ouarzazate and surroundings as our main location, Pasolini and I reimagined the exteriors. The director asked me, then, to go back to the Dino De Laurentiis Cinematografica studios in Rome to check whether the work done so far by Scaccianoce conformed with the exteriors. I had to redress it all over again. Afterwards, when Pasolini came back to Rome, he dismissed Scaccianoce and commended me for having perfectly realized his vision.”

At this point, Dante doesn’t quite know how to proceed and jokes about his age: “I am very young, but I’ve lost my memory behind the curtain.” The audience laughs and applauds vigorously.

“Next, Scaccianoce and I worked at Fellini’s Satyricon (1969). Shooting was halfway through, and the director was looking for a specific beige shade to use on set. None of Luigi’s suggestions satisfied him. I noticed a piece of cardboard on the floor, picked that up, and suggested to Fellini to use that color. He enthusiastically commended me and said that was exactly what he was looking for. From then on, I replaced Scaccianoce as production designer and followed the troupe to the island of Ponza for the remainder of the shooting.”

After Satyricon’s principal photography ended, I got a phone call from Pasolini’s producer, Franco Rossellini, who told me that the director wanted me right away in Cappadocia, Turkey, where shooting for Medea (1969) – an adaptation of Euripides’s tragedy – was about to start.

“Once I arrived on the set, Pasolini informed me that the scene in which Medea (played by Maria Callas) drives a cart at sunset would be shot in four hours. I had to come up with a proper looking vehicle on the spot. The director was completely satisfied with the result. I still didn’t know anything about the movie, but Pasolini reassured me that, in due course, he would tell me all I would need. After shooting in Turkey, we moved to Aleppo, Syria, and lastly to Cinecittà studios.”

At this point, Dante recounts to the audience an eye-opening anecdote about his almost divine halo: “One day, at the entrance of Cinecittà, Federico Fellini stopped me and said: ‘Dantino, I know you’ve worked with Pasolini on Medea. Remember that next time you need to work with me.’ I replied: ‘Maestro, please don’t ruin me. I don’t want to mess up and get fired. Call me in ten years, once you won’t be so mean, and I will be more confident.’

In the following years, Dante Ferretti increasingly became Fellini’s and Pasolini’s essential “deus ex machina.”

The production designer worked on Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life”: The Decameron (1971), Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1974). Then, on the filmmaker’s last effort, Salò or the 120 days of Sodoma (1975), the first installment of the unfinished “Trilogy of Death.”

“Pasolini was a great man. A brilliant intellectual, a novelist, a poet, a director, and a screenwriter. He was a communist.” Then, Dante Ferretti adds: “A communist in a good way, though, not in the Russian sense.”