The “Fleeing Mussolini — Italian-Jewish Refugees in the United States” video was released on Youtube by the Sousa Mendes Foundation (SMF) on November 28th. Opened by Olia Mattis, President of the SMF, and moderated by Natalia Indrina, director of the Centro Primo Levi (CPL), the video featured a short documentary film based on Gianna Pontecorboli’s book “Americordo” and interviews with Annalisa Capristo, an author and academic in Antisemitism and Holocaust studies, and finally Massimo Calabresi, Time magazine’s Washington Bureau Chief.

The video’s combination of Jewish Italian migrant descendants, historical experts in the field of World War II in Italy and the US, and the “Americordo” short film enabled an intimate narrative of the struggles WWII’s refugees endured and a beautiful homage to their contributions to their new home.

Preceding these three speakers, CPL’s “Americordo” documentary was aired, centered on Jewish Italian immigration in the US in the 1930’s. The author of the book to whom the film pays tribute, Gianna Pontecoroboli, tells the audience that she was immediately inspired to write her book upon first joining her uncle in America in the 1970’s. There was something fascinating about the Jewish Italian community; they shared similarities with the Italian American and Jewish-American communities, yet they didn’t quite fit in. The documentary narrowed in on Judge Guido Calabresi and his family’s escape to America. After speaking of his father, drawing on their immigration knowledge to succeed in law, and their embracing of the “outcast” label, the judge concluded, “We were different but not in a bad way, we were ourselves.”

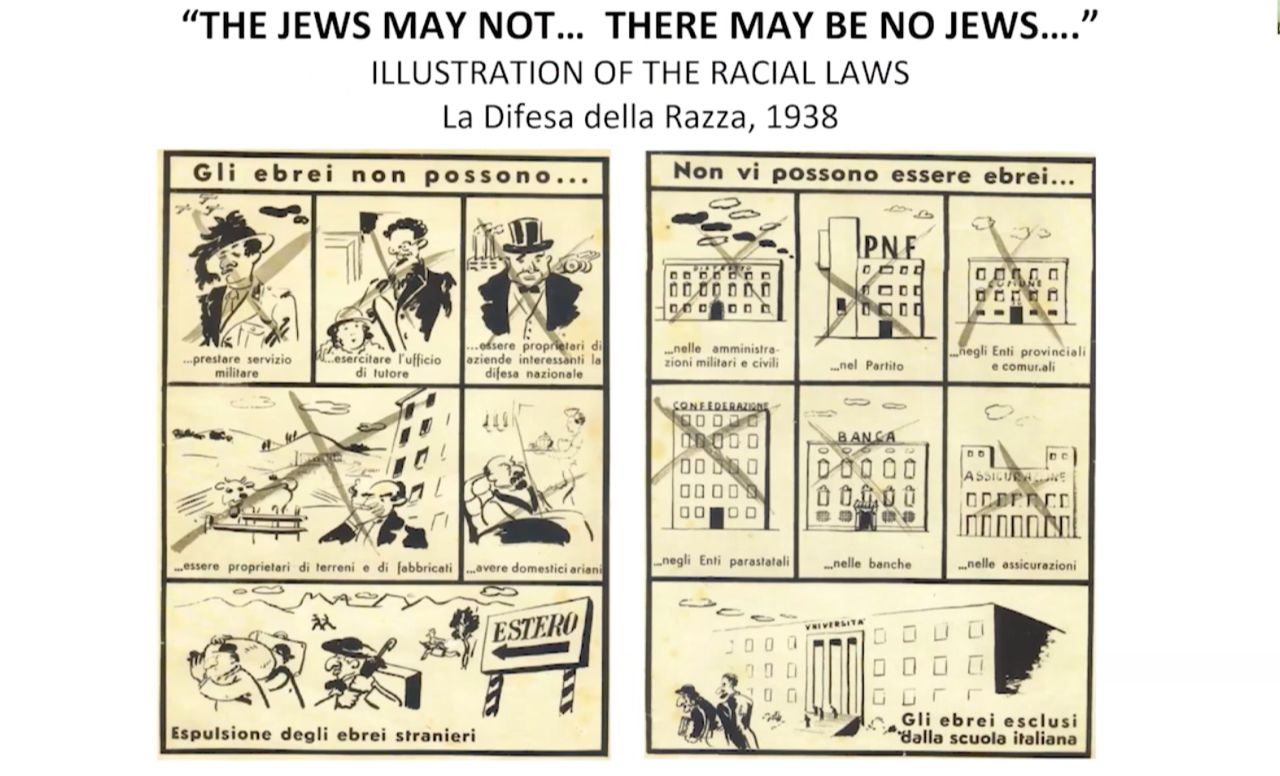

The first speaker, Annalisa Capristo, is an academic and research expert in this specific historical sphere. She began by making an important distinction: “this was a forced migration, not a voluntary exile; persecution forced foreign Jews to leave Italy, Libya and the Italian-Aegean possessions by 1939.” The alternative, Capristo explained, would have been facing persecution and “increasingly burdensome professional and social restrictions that were in place at that time in Italy.”

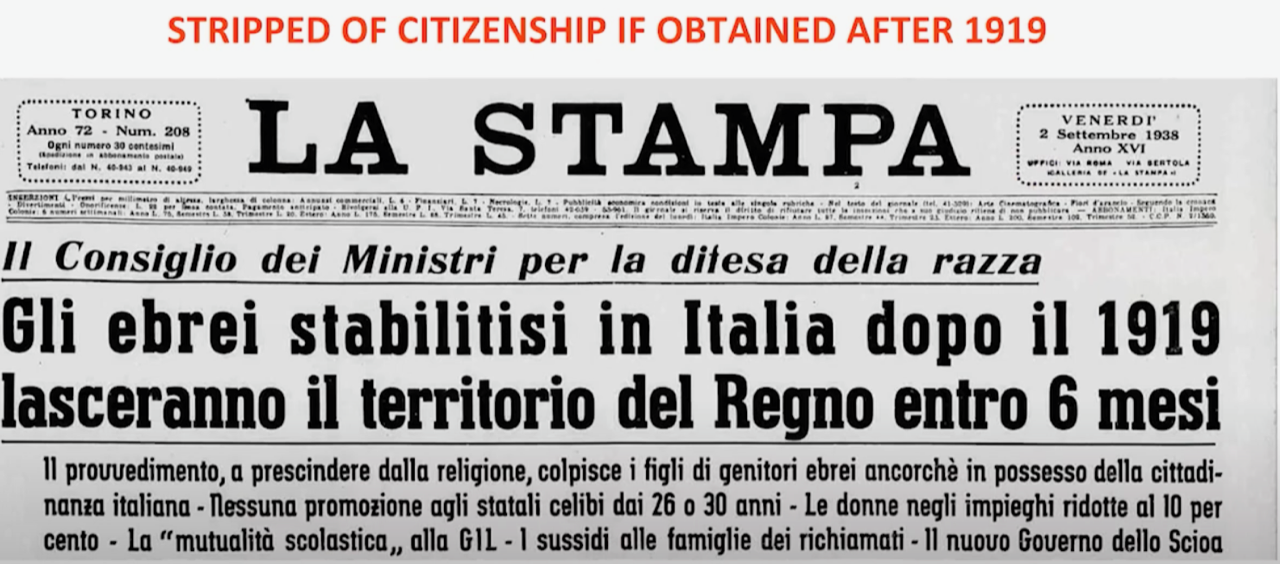

To further illustrate her claims, Capristo shared headlines from three separate 1939 editions of the Italian newspaper La Stampa that announced that Jews were being blatantly rejected as members of the Italian race, students and teachers were being expelled from schools and all recent Jewish Italians that had acquired Italian citizenship from 1919 onwards were being exiled. Furthermore, straying away from numbers and data, Capristo provided stories of Jewish Italian individuals and how the fascist regime impacted them. Among the people she mentioned were publicist Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, music composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Ezio Levi D’Ancona and Saul Steinberg. Some managed to transfer their careers and start over, but others took their own lives in desperation or died from stress-induced ulcers. Capristo reminds us that fascist Italy played a significant role in foreign Jews’ persecution, a role that cost Italy’s society much cultural and scientific development in the long-term. “This is a kaleidoscope of personal and professional stories which deserves to be fully reconstructed,” said Capristo.

Second to speak was the central guest, author and journalist Gianna Pontecorboli. Pontecorboli wanted to gather intimate memories and conversations from a wide range of Jewish Italian migrants with different personal and professional lives. While there were several intellectuals and professionals among the migrants, some were also young business owners; the author tried to emphasize the human experience they shared. Pontecorboli describes their decision of leaving– regardless of their backgrounds– as having been greatly difficult: splitting families, gathering sufficient funds and getting a hold of visas.

What most amazed Pontecorboli however, was discovering “how many gifts this tiny minority could give to their adoptive country.” Young people went to war to defend their new country, many moved to Washington D.C. to help the government and, over the years, the economic and cultural relationship between Italy and America flourished as a result of this new, serendipitous bridge.

Lastly, speaker Massimo Calabresi stressed how close to home their stories resonated with his own family’s history. Growing up in the shadows of the Holocaust and WWII’s atrocities against the Jews, Calabresi expressed a deep gratitude to the other participants and commented on the importance of their work. Concluding the video, “it’s striking to see how the discourse has changed surrounding this topic today, at this particular moment preserving and fostering the research field in this historical sector is particularly valuable,” said Calabresi, most likely referring to current anti-semitism and widespread fascism still demonizing the Jewish community today.