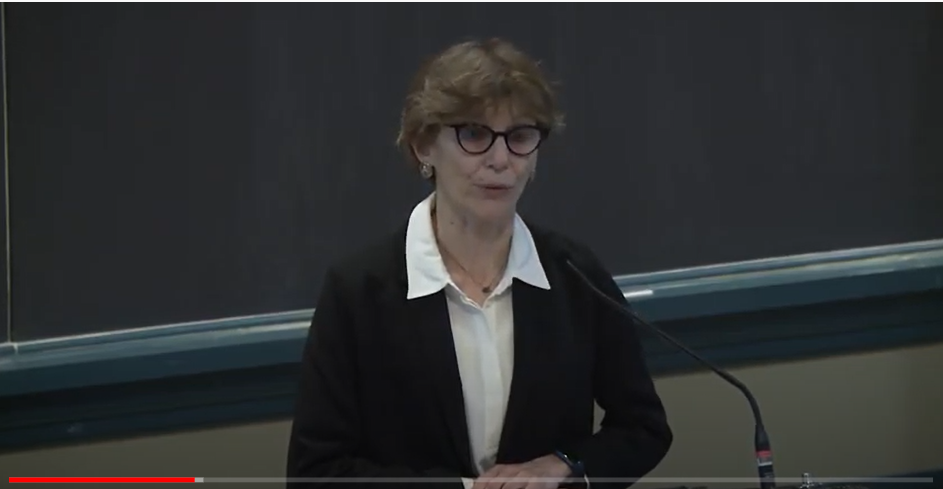

You may already know Ann Goldstein as the standout translator of Elena Ferrante’s tetralogy collectively known as The Neapolitan Novels (commonly known as My Brilliant Friend), but as we will see, there is so much more to her work than that achievement. In the world of translation Ann Goldstein is a star. I’m not engaging in hyperbole; this is simply the widely acknowledged truth. The Wall Street Journal actually did call her a “star translator” and the New York Times “gifted”. The New Yorker editor David Remnick had the highest praise for her: “She’s like a diamond cutter…It’s just an accumulation of refinement after refinement… that makes you a better you.”

This kind of recognition is extremely rare for a translator. Indeed in an interview, Robert Dessaix introduced her not only as a star “on the world stage,” but to drive home the point of how unusual this is for a translator, added, “It’s a particular pleasure to introduce you to someone who normally doesn’t exist”. The profession demands so much dedication that it’s practically a vocation rather than an occupation. Not only is the work arduous, but it requires total concentration and the rewards are very slim indeed in all terms: not only does it pay badly, but there is also very little payback in terms of recognition as well. Rarely do readers even bother to notice the name of the translator as they enjoy the book. The credit for a job well done all goes to the author, but if the translator comes up short, you can be sure that the blame will.

I believe it’s fair to say that it is largely Ann Goldstein’s translation of the Ferrante tetralogy from Italian into English that catapulted that author to worldwide acclaim, leading to what was dubbed “Ferrante Fever.” This “fever” eventually was acknowledged by the academic community—a sure sign that she had reached the highest rung on the respectability ladder– despite the lingering suspicion that her work was not highbrow enough to qualify for academia’s attention. As one member of academia, I harbored no such suspicions and I was convinced that Ferrante fully merited the status of “crossover author”–she was relatable enough to attract the general audience, and deep enough to provide substance for academic study– and so Stephanie Love and I published the first collection of academic essays in what soon became a large, and very crowded field of academics studying Ferrante’s works. In 2018 this successful crossover was confirmed when HBO released a television series of My Brilliant Friend.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V2Yk8xJkMKQ

The fact that Ferrante reached such heights of popularity and recognition in the anglophone world is without a doubt thanks to the quality of Ms. Goldstein’s translation: true to the original, yet immediate and resonant for the Anglophone spirit and “world”.

As a rule, Italian authors receive very little attention on the global literary scene. The exceptions can be counted on the fingers of both hands. Alberto Moravia, Dacia Maraini, Primo Levi, Cesare Pavese and Elsa Morante are among these exceptions. Ann Goldstein has become the premier translator not only of Ferrante, but of Levi, and now, with the new edition of Arturo’s Island, of Morante as well.

Her latest translations are A Girl Returned by Donatella Di Pietroantonio, Farewell, Ghosts by Nadia Terranova and Elena Ferrante’s The Lying Life of Adults. In this interview we chat with Ann Goldstein to uncover some of the complexities and fascinating aspects of translation and what it feels like to spend years in the mind of the author.

Jennifer Maloney in the Wall Street Journal called you a “star translator”. You certainly have achieved the kind of prominence that is extremely rare for a translator. They are pretty anonymous as a rule. To what do you attribute this rare accolade?

“I believe that I owe it all to Elena Ferrante: as Stiliana Milkova writes in her new book, Elena Ferrante as World Literature, ‘Ferrante’s invisibility has enabled the translator’s visibility.’ In fact, ‘star translator’ is really an oxymoron; but if she exists it is as a result of the popularity and success of Ferrante. Readers seem, in these days, to have a need or desire to attach a face, a real person, to a book; I don’t know if it was particularly intense because of the popularity of Ferrante and The Neapolitan Novels or if it was because of the author’s absence—perhaps a combination. In any case, this interest was somehow transferred to the translator. I was very surprised by it: obviously I was not the author and couldn’t speak about the book the way the author might. But I agreed to take on this role of being a sort of representative first because I loved the books and naturally wanted to promote them, and also because I thought it was a way of drawing attention to the role of the translator. I thought it could be a good thing for all translators, who are often forgotten, and good for readers, reminding them that, while they are reading the author’s work, it is thanks to someone else that they are able to do so.”

Classic, enduring works by authors such as Moravia and Morante have been translated over and over. Help us to understand, why translate a book that has been already translated—and in some cases, in a way that has been critically appreciated. Why should it be translated again?

“It’s a vexed issue, in a way. There are those who say that every generation needs a new translation: why this should be, why a work itself doesn’t age (a great work, that is) whereas a translation does, is in some way mysterious. But translations seem more closely tied to their time, and the style of their time, and can easily come to sound dated. Sometimes earlier translations are flawed or cut (Elsa Morante’s Menzogna e sortilegio, for one such example, or Anna Maria Ortese’s Il mare non bagna Napoli for another). In the case of Primo Levi, we were putting together a Complete Works, and wanted to have a consistency of style and tone: the individual books had been translated at different times by different translators. (Here, too, there were different translators, but there was one controlling editor.) New translations can also be a way of reintroducing an author, such as has happened in the past year with new translations of Natalia Ginzburg.

From personal experience, I can say that by translating an author’s work I feel that I know that author– and person– intimately. That I’m inside their head. Can you tell us a bit about the kind of “kinship” that develops between you and the author?

“When you spend so much time—the time it takes to translate a book—in an author’s mind you almost can’t help feeling a kind of intimacy, whoever the author is.

In the case of The Neapolitan Novels, I essentially spent four years not only with the author but with her characters. When I finished the third book, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, I felt bereft: I was so used to having the characters, the words, the rhythms of the sentences in my mind that my life seemed to be missing an important and active part. I was relieved when I began to work on the fourth book.

The second book I ever translated was Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Petrolio—a great, unfinished novel that almost no one has actually read—and I spent several years working on it. At the time I knew very little about Pasolini, and in addition, the book is full of political, social and cultural references. So I had a lot to learn: about Pasolini himself, about Italian politics and culture of the 1960’s and 70’s (and earlier as well), about the topography of Rome. I read his novels and essays and other writings. That was a kind of immersion and though I had nothing in common with him I ended up feeling very intimate with him.”

What kind of kinship do you feel with the work that you have translated? Does it become yours in any way?

“I definitely feel close to almost any work I’ve translated, because I’ve spent so much time with it: even if it’s not literal time, it is an intense period, in which I am examining the work, and thinking about it, in a very detailed way. Even if I have no natural sympathy or commonality with the author, I end up feeling a kind of ownership, and I think every work leaves some part of itself—a word, a phrase, a sensation—in me.”

What are the most challenging aspects of translation in general?

“I’m tempted to say: everything! Primo Levi, who translated into Italian from German, says in an essay on translation that the translator’s most effective weapon is ‘a linguistic sensibility.’ And maybe that’s the greatest challenge—along with the many practical details, such as finding the right word (or deciding on the right word), understanding cultural references and idiomatic phrases and locutions.”

And of translating Italian into English, specifically? What are the traps to avoid?

“One of the main difficulties is that Italian has a much more flexible sentence structure: the basic English sentence is subject-verb-object, whereas Italian can vary that in many ways. First of all, there is gender, which means that modifiers do not have to be near the words they are modifying. Then, Italian verbs include number, person, and the personal pronoun in their form, so they can more easily change position in the sentence: for example, a sentence could start with a plural verb that is followed by multiple subjects. Dialects are a particular difficulty in Italian. As for traps, again I’d like to say everything or anything. But specifically, idiomatic phrases, for one thing: both translating them and recognizing them. False friends, of course. And, precisely because of that syntactical flexibility, making sure that the parts of the sentence go together correctly in English (to take a simple example, that you’ve got the right adjective with the right noun).”

Do you identify with the characters in any way? For example, is it easier to translate a character that is closer to your own profile as opposed to let’s say, a teenager? Or a man versus a woman?

“I almost always identify more or less with the main character, especially a first-person narrator. With Ferrante it has been particularly intense for two reasons: the first is that I’m more or less of the same generation and while my experience is not hers, or, that is, her narrator’s, there are parallels. Second, I think that the author’s absence has in some way meant a closer identification with the narrator. On the other hand, I don’t think this type of identification—whether Ferrante or Primo Levi or, say, Alessandro Baricco—really has an impact on the work of translation.”

Many of the works you translate include Italian dialects. Which do you find to be the easiest and the most challenging?

“All dialects are challenging. Most of my experience is with Neapolitan and Romanesco, so I would say that those are less challenging, maybe because I’ve gotten used enough to them to at least somewhat recognize in a more general way how they diverge from standard Italian.”

As a prolific translator of Italian authors, you are keenly aware of individual styles. What are some of the main stylistic differences between Primo Levi, Ferrante and Morante?

“In the case of Primo Levi, the sentence structure can be complex, but at the same time the sentences are compact, precise, and balanced, and there is a lot of emphasis on the exactness of particular words: as in science. Ferrante’s sentences are dense, often urgent, wanting to get somewhere. I found Morante’s style surprisingly baroque, complex, ornate, in a way”.

I know that you’ve been asked this question countless times, but our readers would like to know, how did you learn to speak Italian and do you actually have to be fluent in the spoken language in order to translate a written work?

“I had always had a desire to learn Italian, and, in particular, I wanted to read Dante in Italian. A class was organized in my office; we studied grammar for a year, learning the basics, and then we spent two years reading Dante. That class went on for many years, although it became more of a conversation class, or group. I took a couple of courses but mainly I read the language rather than speak it fluently.”

Do you believe that translators get enough credit for their work? What changes would you like to see in the industry?

“Like most translators, I don’t believe that translators get enough credit. For example, it is not at all standard for a translator’s name to be on the cover of the book. Reviewers also tend to ignore the translator; sometimes they’ll have an adjective or an adverb, but often the translation as such (even when a reviewer may be quoting large bits of it) is unmentioned. And naturally, I think that translators should get paid more.”

What are you working on now?

“I just finished a book called Distant Fathers, by Marina Jarre, and I’m about to start Borgo Sud, by Donatella Di Pietrantonio.”

Since you spend your time scrutinizing words, do you find that that diminishes your enjoyment of literature in your personal life?

“No, I still love reading: I just don’t have enough time to read everything I’d like to.”