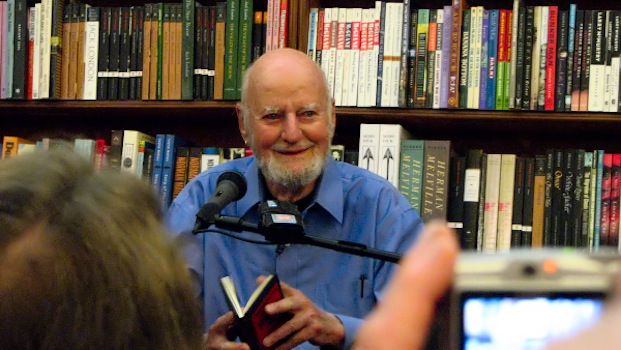

It was a chance encounter, brief—a few minutes, really—when I met Lawrence Ferlinghetti. I was on a West Coast tour for my book “Stolen Figs: And Other Adventures in Calabria” in 2004. I had wandered into San Francisco’s City Lights Bookstore, and just as I was leaving, I spotted Ferlinghetti—taller than I had imagined, blue-eyed, balding, with a full, neat grey beard—descending the stairs from what I now realize were the City Lights publishing offices.

I introduced myself and told him why I was in San Francisco, but just then a visitor he had been expecting walked up to him. Ferlinghetti turned to me, smiled, offered apologies, and asked if I could perhaps come back a little later.

Ferlinghetti had loomed large in my mind and in my literary life from a young age. He was a champion and publisher of many of the Beat writers, whose sense of rebellion and literary abandon captured my imagination and fueled my yearning to escape my home state of Florida for New York City.

The Beats, in part, inspired me to apply for and attend, Columbia University (Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg were undergrads at Columbia in the 1940s; Ferlinghetti received his Master’s in literature there in 1947 before moving to Paris). In 1951 Ferlinghetti moved to San Francisco and, in 1953, he opened the doors to his City Lights Booksellers & Publishers, in the Italian section of North Beach. It became the destination for like-minded writers throughout the country; here, in 1956, he published the controversial poem collection “Howl” by Ginsberg. A year later he was arrested for selling obscene material, and successfully defended the publication in court, upholding the First Amendment.

I walked out of his store and meandered through the streets of North Beach. I passed Vesuvio Cafe, where Jack Kerouac would drink with Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso and Neal Cassady, and stopped for a macchiato at Caffe Trieste. I tried to imagine the neighborhood decades before the Beats made it their home, when it had been filled with immigrants from Genoa and northern Italy.

I turned back and headed down to the Fisherman’s Wharf, from which Joe DiMaggio’s father had set out on his boat for his daily haul of fish. During World War II—just a decade before Ferlinghetti opened his bookstore—those same Italians, deemed “enemy aliens,” were forbidden to go within 20 yards of the dock.

Evening had fallen, and I looked back up Columbus Avenue to North Beach and the uphill walk back to City Lights. But I had other plans, and I never did return that night to connect with Ferlinghetti, thinking I would visit the city another time soon.

While Ferlinghetti was a literary impresario to legions, it wasn’t until I returned to New York City after that trip that I began fully considering him as an Italian American writer.

I re-read his work, searching for Italian references. In his 1958 collection “Coney Island of the Mind,” he offers a hint of Italian when he writes, “Dove sta amore/Where lies love/Dove sta amore/Here lies love.” In the Strand, I picked up “Landscapes of Living & Dying,” in which his famous “The Old Italians Dying” was collected. In the poem, published in 1998, Ferlinghetti observed how in North Beach “For years the old Italians have been dying/all over America/For years the old Italians in faded felt hats/have been sunning themselves and dying.”

Ferlinghetti was born in Yonkers, N.Y., to parents from Italy’s northern town of Brescia, but his father died before he was born, and he was placed in foster care shortly after his birth when his mother was institutionalized for mental illness. Ferlinghetti himself seemed drawn to his ancestral homeland in such poems as “Pound at Spoleto,” about a series of readings by poets in the Umbrian town, and “Roman Morn,” in which he recalls, “Ah these sweet Roman mornings/I open the shutters/high above the back courtyard.”

But it was while researching the life of early Italian immigrants for my second book “Amore: The Story of Italian American Song” that a friend directed me to a poem from his “A Far Rockaway of the Heart,” in which he imagines his father in New York City. In just five lines, Ferlinghetti beautifully captures the immigrant experience:

“And my father drifts by in his fedora

his eyes on the sidewalk

a single Italian lira

and an Indian-head penny

in his pocket”

In April 2019—15 years after that first fleeting encounter with Ferlinghetti—I returned to San Francisco on a spring break trip with my wife and 13-year-old-son and 10-year-old daughter. I was eager to show them the city and the old North Beach Italian neighborhood. We first walked along the wharf, then ventured up to North Beach where we ate cioppino stew at Sotto Mare, walked by Vesuvio Cafe, stopped in Caffe Trieste for coffee, and spent the better part of an afternoon wandering through the maze-like walls of books at City Lights. Just a month earlier, the city had celebrated the 100th birthday of Ferlinghetti, who was not well enough to venture out; instead, hundreds of people gathered outside his apartment building to celebrate him.

Before our spring break trip, I had reached out to a publisher colleague who worked at City Lights, but thought it better not to ask for a get-together with Ferlinghetti himself. It didn’t matter; in my mind, I believed he would live another hundred years. Even now, I believe he still will.