When was the last time that you entered a museum and were moved almost to tears? It happened to me in Florence last week and it had happened only once before in my life: at the immigration museum of Ellis Island, the arrival port in the United States for hundreds of thousands of people from all the poorest parts of Europe (Italy included) between the end of the 1800’s and the beginning of the 1900’s.

In Florence, as everybody knows, there are museums by the dozens and of all types with one of the highest concentrations in the world of masterworks in all visual arts: from the most celebrated Uffizi and Pitti to the smallest and less famous ones, still jewels of incomparable treasures. The entire city is a living museum, and the entire historic center is recognized by UNESCO as a world heritage site.

No one better than Giorgio La Pira, the sainted mayor, responsible for the cultural and spiritual rebirth of the Tuscan capital from the ruins of World War II, has ever captured the unique mission of his adopted city: “Florence has its own universal mission in the system of human and Christian civilization; to the intensely active dynamism of the modern world it introduces a balancing element of rest, beauty, contemplation and peace. In fact, for human beings of all the continents it serves as a pure haven, a delicate oasis that constitutes for all a gift of moral elevation, of proportion, of measure. It is for this reason that Florence belongs, in a certain manner, to all the nations and to all humanity.”

One of the most recent additions to the vast artistic and cultural offerings of the city is the Museo degli Innocenti. Inaugurated in 2016, it tells the story of an institution that for six centuries has been charged with the protection of infants and minors. When Francesco Datini, a merchant from Prato, died in 1419, he left his fortune for the construction of a hospital for abandoned infants and the protection of minors, and entrusted the construction and the management to the guild of the Silk Merchants, one of the more powerful and prosperous corporations that constituted the political and economic backbone of Florence between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The first extraordinary and moving decisions of the Florentine merchants was the choice to place the orphanage under the protection of the Innocent Martyrs (infants exterminated by Herod’s order after the birth of Jesus) and to entrust the project of the entire mammoth structure to Filippo Brunelleschi, with Leon Battista Alberti as the superstar of the movement. Obviously these silk workers were shrewd businessmen and well-travelled, but they were also conscious of the responsibility that their wealth signified vis-a-vis the community of citizens and believed that the poor, in this case abandoned children, were as entitled to beauty as they. It would be as if today Confindustria (the General Confederation of Italian Industry) or Connfcommercio (Association of Italian Businessmen) entrusted the building of a center for the welcoming of migrants to a Renzo Piano or to a Santiago Calatrava.

But let’s return to the Museo degli Innocenti. As you enter the ground floor your heart will break as you read the stories of the thousands of infants who went through these halls, stories told in scrolls, document fragments, broken devotional medals, some shreds of fabric that the mothers had placed in the swaddling bands of their children before entrusting them to the wheel and to the care of the Institute. Many of them hoped that these ‘relics’ miraculously inventoried in the records and saved in the archive, would make it possible to be reconnected with their children in better times.

While you are still reflecting on these stories, you will go up the stairs and you will find yourself immersed in the Art Gallery of the Ospedale. Here you will find works by some of the great masters from Della Robbia to Botticelli, from Ghirlandaio to Piero di Cosimo: altar pieces, paintings, statues, glazed terracottas that embellished the chapels reserved for diverse groups of guests, from little girls to little boys, from nuns to wet nurses.

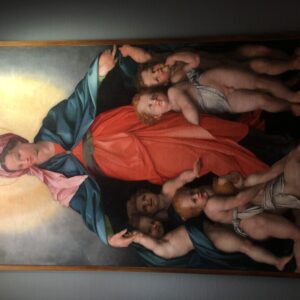

Among the many marvelous images, I take one away with me that is impressed on my memory: the “Madonna Protectress of the Innocents” by Jacopino del Conte. The six children that are under her mantle are plump and healthy looking. Some seem to be playing and joking. One munches on a piece of bread, but nobody smiles. The loving care and the extraordinary beauty that surrounded them were not sufficient to give them the happiness of a cuddle or the joy of a kiss. And at this point, before you emerge once again in the dazzling sun of the Piazza dell’Annunziata, go ahead and cry a bit, it will make you feel more human and besides, wearing your mask, nobody will notice.

Translated by Salvatore Rotella