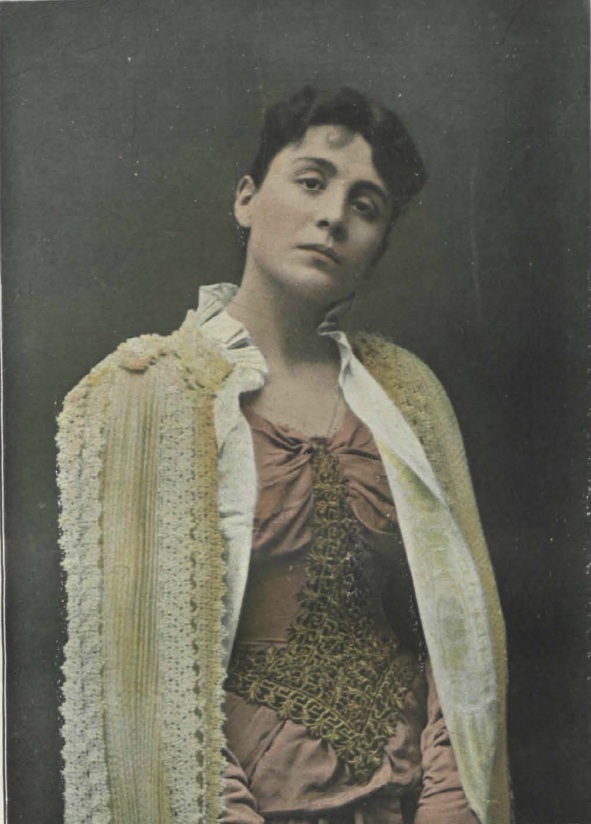

If there is an Italian actress who has left an important mark in the world theater from the nineteenth century to today, it is Eleonora Duse. She was born into the theatrical life, as happened often in those years when the theater was, above all, a family inheritance. She was born on October 3, 1858, in Vigevano while her parents were on tour. Her parents were modestly successful traveling players. She died very well known on April, 1924, in Pittsburgh, during her last American tour. About her Charlie Chaplin wrote: “Eleonora Duse is the greatest artist I have ever seen. Her technique is so marvelously finished and complete that it ceases to be technique […] Duse is direct and terrible”. Marilyn Monroe, for her part, always kept a photograph of her in her pocket, while Lee Strasberg, teacher and artistic director of the Actors Studio, transmitted her unconventional way of being on stage to students who would one day become stars in Hollywood.

Since 2015 “the Divine”, as Gabriele D’Annunzio, her seducer and treacherous lover, had nicknamed her, became the theme of a ballet never performed outside Hamburg, before its author, the eighty-one-year-old American choreographer John Neumeier, set it up in Venice. The lagoon city has preserved, since 2011, the largest archive of documents on the life and art of Eleonora, thanks to the Istituto per il Teatro e il Melodramma of the Fondazione Giorgio Cini. Venice has recently been invaded by destructive flooding. Moved by the disaster, the choreographer literally donated the European debut of his Duse – Choreographic Fantasies about Eleonora Duse, to the Teatro La Fenice. These Fantasies are typecast not only to his splendid Hamburg Ballet dancers, but above all to the unique, great tragédienne today able to take on such an important role: Alessandra Ferri. On her petite body, as flexible as a blade of grass swaying in the breeze, and which brings maturity as an exciting interpretative and passionate light, Mr. Neumeier has built a memorable character leaning on wonderful music by Benjamin Britten and Arvo Pärt, readings, scraps of lived and scenic life without a true chronological order.

Everything begins in the dim light of the stage. A segment of Cenere is shown: taken from the eponymous novel by Grazia Deledda, it is the only film that was interpreted by Duse in 1916. Alessandra / Eleonora now looks at “herself,” enclosed in a skimpy long, black dress, while a row of old theatrical seats on which the audience sits, and also stand, begins to rotate around a small stage. Conceived by Neumeier himself, costume designer, too – this “theater in the theater” will rotate from left to right and vice versa for all ten scenes of the first part of the ballet.

In the first scenes, the near-dark does not abandon us: the horrors of the First World War that struck Duse so much, are evoked. Alessandra/Eleonora dances with two soldiers; she kisses one of them, her real and belated almost-maternal friendship (Luciano Nicastro) and returns to her adolescent debut in a vaguely jester-like parade of bright color. Here she clings to one of the interpreters (perhaps the husband, soon abandoned in real life, from whom she had her daughter, Enrichetta).

Instead the white flowers, given to her by the soldier she kissed, will be part of the beautiful scene dedicated to Romeo and Juliet, caught at the moment of the death of both. The snowy petals, behind which the still shy adolescent Duse perhaps only dreamed of playing that Shakespeare, serve, now that she has become Juliet, to cover the dead body of Romeo. With this death and in a flash of blue light, the war and soldiers that invade everything return, crawling to the proscenium.

But then comes the beautiful and emphatic Sarah Bernhardt, dressed in pink. She dances The Lady of the Camellias. The rivalry between the two actresses is well known: here the minute Alessandra/Eleonora is slothful. First, she brings her a bouquet of red roses in token of admiration, then she makes fun of Sarah in a funny imitation that says everything about what Duse did not love: exteriority, theatrical clichés of a fake and bourgeois theater. She craved interiority, identification, naturalness. The audience that had shouted “brava, brava” to Sarah leaves; then it returns to admire another intense and feverish pas de deux of the ballet’s protagonist. With the arrival of Arrigo Boito, mentor, lover and then friend of Duse, only books and glasses dance. Even Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, translated by Boito for Duse, results in the dressing in a damask dress by Alessandra / Eleonora: immobile, with arms wide open.

Isadora Duncan could not have been left out of this choreographic portrait. Letters, documents, photographs confirm how much Duse was a comfort to the Pioneer of free dance when she lost her two children drowned in the Seine. Here Duncan expresses herself in a blue and Greek tunic within a small lateral rectangle (another “theater in the theater”). There are many moments of the extremely expanded but instructive ballet, in which Ferri dances, her beautiful arms in the wind, with Duncanesque impetus. But then it is the pointe shoes fitting her envied cou de pied launching her into a couple dance with an academic tone, yet full of original steps, fractures, dramatic outbursts. It is unseemly for Alessandra / Eleonora to see her rival Bernhardt in the role of Marguerite Gautier and with her partner who undresses, also evoking the betrayals of her beloved D’Annunzio through his work: to Sarah he devoted theatrical dramas that were instead written for her. Moreover, the Casanova Gabriele also goes by, in a top hat and looking haughty: headed for new female conquests.

The one who remains, however, is th soldier of the beginning, as the fil rouge of the dance drama, embodying himself but also other roles. When he is about to die on a (real) hospital bed, Alessandra / Eleonora runs to bid him farewell. Then she goes back to the “theater in theater” – the scene, Neumeier says, is her real consolation – while her own end is going to be prepared. A video takes us back to the beginning of the ballet: it is no longer Cenere, but it is the very crowded, regal, funeral of the actress. Once again in her black dress and enveloped by the warmth of the governess Désirée, Ferri fights against a rain storm also projected on a small screen. In an instant, she falls to the ground and is carried in triumph by her audience, while the hearse of the black and white film runs until the curtain closes.

Buried in Asolo and by her own will with the tomb facing Monte Grappa in honor of the fallen of the First World War, Duse returns in a leotard in the second part of the ballet, for a dance on a blue, sky-blue, white and gray background, with four male partners, projections of her most important loves: Boito, D’Annunzio, the soldier Nicastro and the Audience.

Any form of narration disappears; the choreography, mostly to music by Arvo Pärt (Frates), with the appropriate Cantus in memory by Benjamin Britten, closes and opens around her. Ferri often remains seated in profile while the four bare-chested men in white or black pants turn, jump, huddle together and line up. At the second tolling of the bells, on Britten’s funeral song, they open their arms and vanish. She remains, her back to the audience.

In Duse – Choreographic Fantasies about Eleonora Duse by John Neumeier, shines the skill of the whole Hamburg Ballet with Silvia Azzoni, Alexandre Riabko, Alexandr Trush, Anna Laudere, Marc Jubete and the mighty and disheveled guest Karen Azatyan, perfect in pairs with Ferri and in transmigrating from character to character. The ballet will be on tour: both Venice and the Teatro La Fenice have clearanced it.

P.S.

The temporary exposition at Fondazione Cini in Venice, open from February to July 2020, is dedicated to Antony and Cleopatra, translated and adapted by Arrigo Boito. The purpose is to shed a new light on one of the three Shakespearean scripts held among the actress’s papers and on the fortunate fate that the drama had on the scene at that time. After a controversial debut, taking place on the 22nd of November 1888 at the Teatro Manzoni in Milan with the lavish setting up by Alfredo Edel, the show became one of the signature tricks of the actress during the long tournée in Russia, in 1889. The exhibition could be visited by reservation, calling the number (Italy) 041 2710236 or writing to ti.inic@ammardolemortaet.