They knew each other, but they did not love each other. Actually, they tried avoiding each other if they could. They were about 20 years apart in age and came from the extraordinary 15th century Florence, then a nominal republic controlled in a discreet and enlightened manner by the Medici. Glorified by their peers for their multiple talents and sought after by the princes of the time with pounds of gold – but also gossiped about for their open homosexuality – their names are synonymous with the Renaissance and, inevitably, are associated, perhaps before anyone else, with the term ‘genius.’ So noteworthy are their names that they do not even need last names to be defined, hence Leonardo and Michelangelo.

More than five centuries following their troubled lives, in this unusually balmy fall season in New York, they are the stars: Leonardo with the auction of a Salvator Mundi attributed to him with the record price of 450 million dollars, and a new biography at the top of the best seller lists, and Michelangelo with the exhibit, “Divine Draftsman and Designer” (at the Metropolitan Museum until February 12, 2019) recognized unanimously by critics, journalists and intellectuals as the cultural event of the year.

Too much has already been written about the painting that Christie’s auctioned off for such an absurd amount: from moral considerations regarding the transaction to reservations about the authenticity of the piece; from the poor state of preservation to the clumsy restorations carried out throughout the centuries from the derisive definition of male “Gioconda,” to the hypothesis about the buyer’s identity. I believe that we can all agree on one fact: a painting was not sold that Sunday, but rather, its attribution to Leonardo.

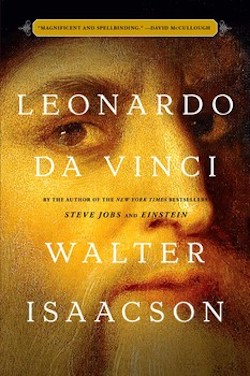

The new biography on Leonardo (Simon & Schuster) came out in October and immediately hit Best Sellers lists. The author, Walter Isaacson, is a specialist in biographies of geniuses (including, among others, Benjamin Franklin and Steve Jobs), and although he does not reveal any clamorous news on the life of the painter, scientist, engineer, and inventor – given that his years-long romantic affair with a younger man is by now common knowledge –he presents a fascinating hypothesis: an illegitimate birth, the inability to have access to regular schools and universities and, consequently, an erratic and autonomous education by a self-taught person with an insatiable curiosity, were the conditions that allowed a young man with undoubtedly extraordinary intelligence to transform himself into a genius. The film rights to the new biography have already been purchased and it seems certain that another Leonardo (di Caprio) will play the role of his namesake.

The new biography on Leonardo (Simon & Schuster) came out in October and immediately hit Best Sellers lists. The author, Walter Isaacson, is a specialist in biographies of geniuses (including, among others, Benjamin Franklin and Steve Jobs), and although he does not reveal any clamorous news on the life of the painter, scientist, engineer, and inventor – given that his years-long romantic affair with a younger man is by now common knowledge –he presents a fascinating hypothesis: an illegitimate birth, the inability to have access to regular schools and universities and, consequently, an erratic and autonomous education by a self-taught person with an insatiable curiosity, were the conditions that allowed a young man with undoubtedly extraordinary intelligence to transform himself into a genius. The film rights to the new biography have already been purchased and it seems certain that another Leonardo (di Caprio) will play the role of his namesake.

The Metropolitan exhibit highlights above all Michelangelo as designer and draftsman, with more than 130 sketches, and only three marble statues and one wooden architectural model. But the idea guiding the exhibit is that precisely in Michelangelo, everything begins with design: from barely-hinted sketches to the fresco cartons; from building projects and fortifications to the precise anatomical tables that would serve in preparation of his sculptures and frescos. But many of the drawings of human figures finish, in turn, with the plasticity and three-dimensionality of the sculptures, again raising the question of what is finished and unfinished in Michelangelo’s works. If you’re not able to come to New York, take a look at the Metropolitan Museum’s marvelous website to get a thorough idea of the richness and depth of the exhibit.

The Metropolitan exhibit highlights above all Michelangelo as designer and draftsman, with more than 130 sketches, and only three marble statues and one wooden architectural model. But the idea guiding the exhibit is that precisely in Michelangelo, everything begins with design: from barely-hinted sketches to the fresco cartons; from building projects and fortifications to the precise anatomical tables that would serve in preparation of his sculptures and frescos. But many of the drawings of human figures finish, in turn, with the plasticity and three-dimensionality of the sculptures, again raising the question of what is finished and unfinished in Michelangelo’s works. If you’re not able to come to New York, take a look at the Metropolitan Museum’s marvelous website to get a thorough idea of the richness and depth of the exhibit.

But why is it that after centuries, these two Tuscans remain at the center of cultural life in the capital of modernity? I venture three hypotheses: in times of moral, value, and identity crises in the Western world, Leonardo and Michelangelo have remained pillars of stability that reassure us of our model of civilization. On the other hand, the criticism that has been all the rage on American college campuses since the ‘70s against a culture monopolized by “white, dead men”, and that has rightfully precipitated a pluralist diversification in curriculum, had to accept the evidence that Leonardo and Michelangelo fully deserved the place that they had always held in Western culture. Their peculiar capacity to always combine humanistic and scientific culture in a creative manner will continue to be the only recipe for success. Not because a new generation of geniuses is in the making, but because only a culture that is not exclusively scientific or humanistic has the potential of winning the challenges of the future.

Translated from Italian by Emmelina De Feo