LEGGI QUESTO ARTICOLO IN ITALIANO

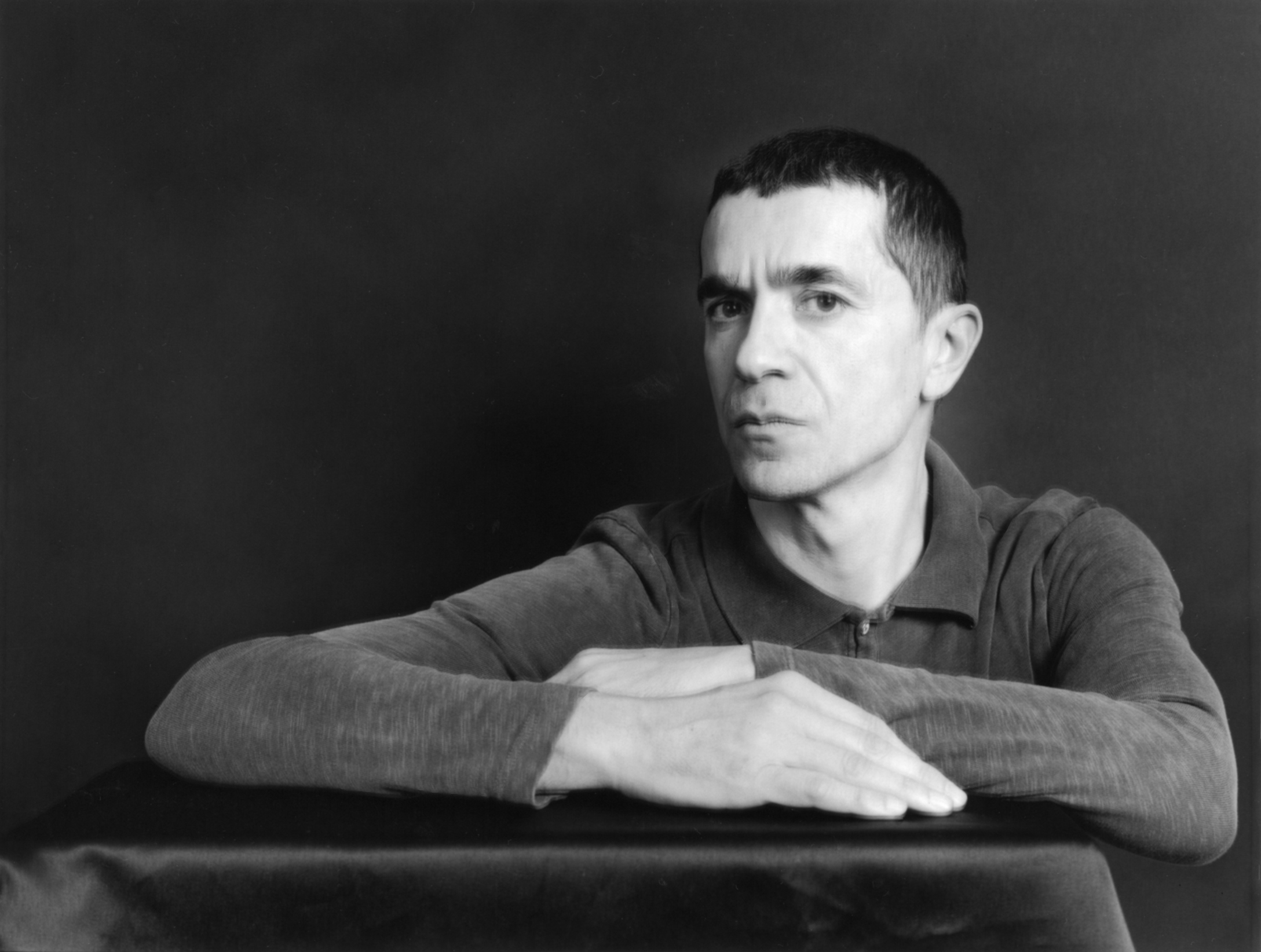

It may have been because of the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement received in 2013, at the age of 53, so by now the name Romeo Castellucci circulates insistently. There have been articles, books, essays written about him. His theatrical works have been glorified and despised. Certainly since the beginning of the ’80s, Romeo Castellucci has established himself as a unique and potent voice of contemporary theatre.

It was 1982 when, in Cesena (in the Emilia-Romagna region), with Claudia Castellucci and Chiara and Paolo Guidi, he founded the Societas Raffaello Sanzio that questioned the conventions of theatrical productions in favor of an experiential performance that was searching for the paradox of form and content. The group declared itself iconoclast and was even charged with blasphemy. Over the years, Castellucci’s work has changed and to some extent, he moved closer toward theatre but he did not soften: his productions deconstruct the spectator’s point of view and brings the spectator to almost physical contact with theatrical action.

I meet with him in a hotel in the Financial District where he is staying while he prepares for the two dates (Saturday, October 1st and Sunday, the 2nd) when Julius Caesar. Spared Parts will be performed in a site specific setting, among the marble and columns of Federal Hall, an institutional historic building of New York that witnessed the birth of American democracy as well as finance. The show comes to the city within the Crossing the Line Festival, organized by French Institute Alliance Française.

This production is a condensed version of his 1997 Julius Caesar for which he was awarded the best performance of the year (Ubu prize). A 45-minute performance that boils down Shakespeare’s play to three scenes, fragments, pieces of action of a text that is, perhaps, among the most known plays in Western theatre. Castellucci rearranges it to create powerful cognitive clashes.

You are presenting your Julius Caesar here in New York. Is there still something new that could be said about this piece?

“On this piece in particular there is always something more to say. It’s a piece that deals with power, circular speech, rhetoric. But it also speaks of human beings, especially in the second part that is extraordinary and that in some way contradicts the first part, which is more political. And, as often happens with Shakespeare, it is still quite current. They are texts that are infinitely interpretable, and here lies the strength of Shakespeare. He is also a generator of mythology. I believe that the most interesting thing is to reveal an unexpected side to the text and to look to present it under a new light, in a new way.”

How do you achieve this in your performance?

“Reading Shakespeare’s text between the lines and having had first read Roman history, it’s understood that Julius Caesar is not a man of power. He is a man that gets caught in a power struggle but he is not powerful. Shakespeare immediately with his opening lines presents Caesar as a sacrificial lamb.”

Does the theme of power interest you? Have you explored it in the past?

“Not as directly as I do now. Here the work is calculating speech, that is armed speech, rhetoric. The destinies of Rome and history depended upon the beauty of discourse. Mark Anthony’s speech was more beautiful and moving than Brutus’ and Mark Anthony became a Triumvir because he gave a great speech. Brutus instead had to run away, committing suicide because he erred in his speech. That is the power of speech and still today nothing has changed. We’ve had a recent example the other day with the first presidential debate…”

There is speech then there is the body. In your theatre the relation between body and speech seems to be very organic. Is there a mindset behind this dynamic?

“More than a mindset there is a probing, a search to penetrate the word, that isn’t a given but a gesture fraught with consequences. Speaking is problematic. Since tragedies, the basis of Western theatre, there is man’s idiosyncrasy with respect to language. Man wishes to say things that language is unable to express. This lack of accuracy generates catastrophes. For this reason, speech in tragedies generates silence.”

So the body can fill this shortcoming?

So the body can fill this shortcoming?

“The body is subjected to the language, it is invaded by it, but at the same time, it is an element of truth. Language is an element that is instead very tied to power. The body is a more fragile element that adheres to existence. Language is always a stratagem. Then, sometimes, the body also gets vindicated. For example in this setup there is an actor that speaks and to do so he inserts an endoscope in his nostril that goes down his throat around his vocal cords that vibrate. The spectator sees in real time his vocal cords that move and generate language. This is to say that even language has a physical basis that is biological and mechanical and it’s the same for everyone.”

You often revisit ancient history and myths in your works. Do you maintain that this aesthetic and ethic are relevant today?

“Mythology isn’t something connected to the past, myths are generated every day. Walk down the street and you can recognize certain mythologies that persist. Mythology is an attitude on life, it is not solely something academic, dusty: just the opposite. Whoever is capable of creating myths, and also reading them, has an additional tool to interpret reality. Mythology is part of human nature, it’s not an invention. Mythology produces rational thought. Also man needs stories, and mythology is storytelling.”

This is the first time that you are staging a performance in New York…

“In the city proper, yes, but I’ve been all over the States.”

What are you expecting from a New York audience?

“We’ve worked often in America and I don’t think New York is very different. There are nuances, for sure, but in general I think that the American public is absolutely ready, maybe even more so that Europeans who have more convictions tied to history and that often becomes a burden, a dead weight. Here it seems to me that there is a different concept of history and greater open-mindedness.”

Do you think that there is something Italian or italic in your way of doing theatre?

“Without a doubt. I am an Italian author because I was born in Italy and my references are those shared by all Italian children in my era. Like all Italians, I was raised Catholic, a peculiarity in which art history plays a powerful role. Beyond doctrine, which doesn’t interest me, Catholic culture is powerful and powerful is its link with art history: Caravaggio would never have existed outside of this culture.”

An aesthetic conditioning, then, more than ethic…

“Yes, absolutely. It is nothing doctrinal or about faith. The Catholic church, for better or worse, had an immense impact on culture and the arts. As a child, you go to church and see the paintings, everywhere, with nude scenes. The first naked bodies I saw were in church. Catholicism is a very sensual culture, very tied to sin. Much more than the Protestant, Lutheran or Calvinist culture that was washed with bleach. Catholic culture remains tied to a certain idea about the body and sin.”

Your theatre manages nonetheless to always go beyond Italian borders, something not common for our domestic Italian theatre. In your opinion, what is it that makes your theatre exportable?

“In reality, I don’t do anything to promote my work. It’s the work that produces work. I’m not really sure how these mechanisms work but I know that I work mostly abroad, very little in Italy. But it’s not a thing that I sought, and, actually, I feel bad. I use Italian speech and in my texts there are also references to Italian culture: I believe that I am recognized as Italian, yet they request me more abroad…”

When you come to New York, do you go to the theatre? What are you interested in seeing?

“I always have little time, but here it seems that theatre is rather conservative. There are theatre groups here in New York that are very interesting, that I admire, like the Nature Theater of Oklahoma, Richard Maxwell, then there are legends like The Wooster Group and Richard Forman. When compared to the size of the city, however, there is a disproportionate number.”

Is there anyone in American theatre with whom you would like to work?

“My next project will star Willem Dafoe, a founding member of The Wooster Group.”

What will you be working on?

“An adapted text from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story, The Minister’s Black Veil. The world premiere will be in Anversa in December, then we will come to New York too.”

It is often said that your theatre is moved by the ideal to render theatrical language comprehensible. What does it mean? What need is there? And how do you do it?

“I think a performance does not need to be made for your friends or for theatre specialists: it’s not a club. You could be as sophisticated as you want, but you must be able to reach the greatest number of people possible. If it’s not comprehensible, it is weak. But comprehensible must be defined. I don’t do educational things, I’m not Bertolt Brecht who wants to educate. But it is something however that everyone, in their own way, can understand and interpret.”

Does understanding come more from your head or gut?

“First it comes from the gut, then the head: the first impact must be emotional, this is the only way to reach the spectator. Theatre is also the art of contact, of proximity: the stage, the actors, the action. Without contact it doesn’t work, it remains inert, a dead letter.”

New York. What do you think? How are you living it?

“It’s an inevitable city. It’s very present in all of us, for many reasons. The thing I like most is the people. In the subway, I could stay there for hours people-watching. The variety of people is what makes New York unique. And I’m also really connected to American literature…”

Something in particular?

“I’m devoted to David Foster Wallace who, unfortunately, screwed us… He remains one of my points of reference, not only in literature but also in philosophy. He was one of the few writers, indeed one of the few people in the world able to provide a humane look without being cynical on all that surrounds us. Before being an extraordinary writer and artist, he was an extraordinary person.”

Translated by Enza Antenos.