How is the war going to end in Ukraine, and what exactly does the West want in Ukraine? The question, while the fiercest war since the end of WW II is exploding in the center of Europe, in a rational world ought to be addressed with the maximum urgency. Surely, this is what the United Nations was created for. And why are the Blue Helmets of the UN not intervening with a massive peacekeeping operation to keep the belligerents apart?

Fair enough, any practitioner in international affairs would respond. But reality is different. The Blue Helmets intervened with little or no success in the Korean War, in the Middle East, in Former Yugoslavia and in other parts of the world. The UN peacekeepers were, and are, invaluable in local conflicts, generally in the most remote parts of the world and when geopolitical interests of great powers are not in question. Otherwise, irrespective of humanitarian conventions and international law, the Stone Age principle that Might Makes Right prevails.

The humiliation of UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres in his recent belated peace mission to Moscow is an example. For the meeting with Putin, with grotesque symbolism, the Kremlin brought out the Long Table. Guterres, eschewing controversy, said simply that he understood that on the Ukrainian crisis there were two very different positions. According to the UN charter and international law, the Russian military intervention was a flagrant aggression. Russia thought otherwise. But the SG had come as a messenger of peace. As a first step to negotiate a peaceful agreement, he was ready to act as a mediator for an unconditional ceasefire. That was surely in both parties’ interest.

Putin at the end of the long table looked somber. In a lengthy monologue, using a funereal low tone of voice, he reiterated his position. Russia would not sign a peace deal unless Ukraine first agreed to “solve the issues of Crimea and Donbass”. Guterres on the opposite side of the table took meticulous notes with a long pencil on a legal notepad. He did not ask questions or interrupt. There would no point. Then he flew to Kyiv to report to Ukraine’s president what he already knew: “failure of a mission”. That incidentally, was the despairing title of the book by sir Nevile Henderson, British ambassador to Berlin, in the days of Hitler. On Sunday September 3, 1939, at 11 a.m. WWII, another war that nobody wanted, had started. It would last 5 years.

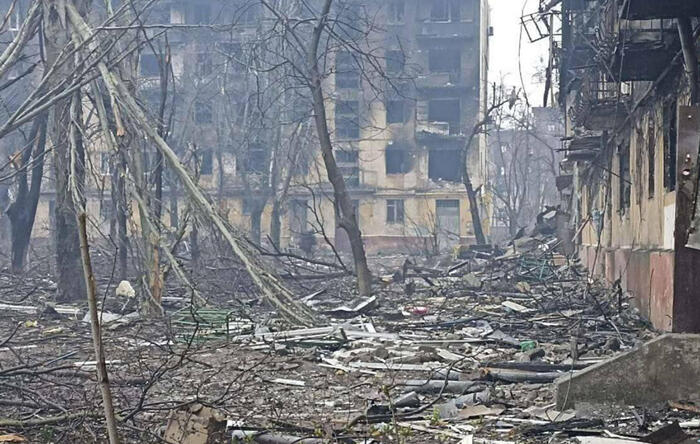

ANSA/FORZE ARMATE UCRAINE

In Ukraine 2022, it is hoped, there is still a chance to prevent an even more tragic catastrophe. But time is running out. As social scientist Boaventura de Sousa Santos points out in an Opinion article in the Wall Street International, world leaders on both sides of the Atlantic are incapable of projecting a coherent political strategy. Like a large segment of distracted public opinion in the West, they assume that the Ukrainian tragedy somehow will be over, sometime in the near future. In other words, they are fatalistically “sleepwalking into the unknown”.

Meanwhile, to appease their consciences somehow, the United States with Europe, Australia and other parts of what, for lack of a better definition, can be described as the non-authoritarian “free” world, increasingly supply Ukraine, the victim of Russia’s brutalist attack, with financial assistance, military training–including intelligence and, above all, plenty of arms. Democracy must prevail over dictatorship, is the slogan. This is admirable in an idealistic society. But unfortunately, the world–free and not free–has to face some immediate problems. With the Russian blitzkrieg aggression an obvious failure, the Ukrainian conflict has already become a grinding war of attrition that may last for months or even for years.

Worse still, the war of attrition which Russia has now launched, with devastating effects on Ukrainian cities, risks becoming a highly dangerous war by proxy, where Ukraine unwittingly assumes the role (in the ghastly terminology used by strategists) of “country of sacrifice”. This is morally repugnant, no doubt. But, with the systematic destruction of Ukrainian cities and infrastructure, and up to 6 million refugees already fled mostly to Europe, and no realistic political initiative in sight, the question, posed by Foreign Affairs, the journal of the Council on Foreign Relations think-tank, to the US administration and NATO allies, becomes: what if the war in Ukraine does not end?

With typical frankness, unusual in his role, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin (a former general) in his recent visit in Kyiv provided an answer that raises an even more fundamental question. “We want to see Russia weakened” Austin said, “to the degree that it can’t do [what] it has done since invading Ukraine”. Was he alluding to the West expanding war aims, or even perhaps implying that a longer war in Ukraine might be a useful objective to discourage and further degrade Russian aggressions? Surely Americans and NATO allies, if their commitment in the conflict expands, would be entitled to know.

(c) 2022 VNY La Voce di New York/Longitude Magazine.