On until January 9 at Rome’s Scuderie to celebrate the seventh centenary of Dante Alighieri’s death is the blockbuster exhibition, Inferno (Hell). Devised by French art historian Jean Clair, and curated by him with his Italian wife and fellow art historian Laura Bossi, it’s the first art exhibit ever dedicated to the first canticle of Dante’s Divina Commedia (1320). An odd coincidence, since over the centuries Inferno has inspired artists and writers far more than the somma poeta’s subsequent canticles.

Through its 232 works-of-art on loan from over 80 major museums and prestigious public and private collections in Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, The United Kingdom, and the Vatican, “it aims to highlight the definitive allegorical meaning of Dante’s great theological fresco,” said Clair at the opening’s press conference. That’s to say: to show humanity a path of liberation from the miseries and horrors of “the little threshing floor that so incites our savagery” (Paradise XII, 151,) towards a condition of happiness and salvation as Dante optimistically states in Inferno’s last verse: “E quindi uscimmo a rivedere le stelle.”

A large number of loans come from Florence’s Uffizi Galleries, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, London’s Royal Academy, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Valladolid’s Museo Nacional de Escultura, and Lisbon’s Museu National de Arte Antiga. The most famous artists represented are Beato Angelico, Botticelli, Bosch, Brueghel the Elder, Goya, Manet, Delacroix, Rodin, Cezanne, von Stuck, Balla, Dix, Taslitzky, and Kiefer.

Except for the introductory excerpt from Inferno, the 1911 silent movie, and the first room, the works of art are all displayed in chronological order. All recount the persistence of Hell’s iconography, the world of the damned, although in different media and styles, from the Middle Ages to the present day.

On display in the first room is the exhibition’s most spectacular work: a 7-meter tall colossal plaster cast of Rodin’s monumental Gates of Hell (1:1 scale fusion model). On loan from the Musée Rodin in Paris, the press release reports that this cast was “made in 1989 through the fusion of one of the last bronze specimens of Rodin’s work.” Inspired by Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise at the Baptistery in Florence, Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgment, Delacroix’s The Barque of Dante, Balzac’s collection La Comédie humaine and Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal, it was commissioned in 1880. Rodin worked on and off on this project for 37 years, leaving it unfinished at his death in 1917. That year a model was used to make the three bronze casts, now in Paris, Philadelphia and Tokyo.

The rest of Inferno is divided into three sections. The first, on the Scuderie’s first floor, are works of art directly inspired by Dante’s text. The second and third sections are on the second floor. On display in the second section are works of art based on the Hell created by man. Hidden by a wall from section two, so it comes as a surprise, is “Redemption”: a room entitled Riveder le stelle, from the last verse of Inferno.

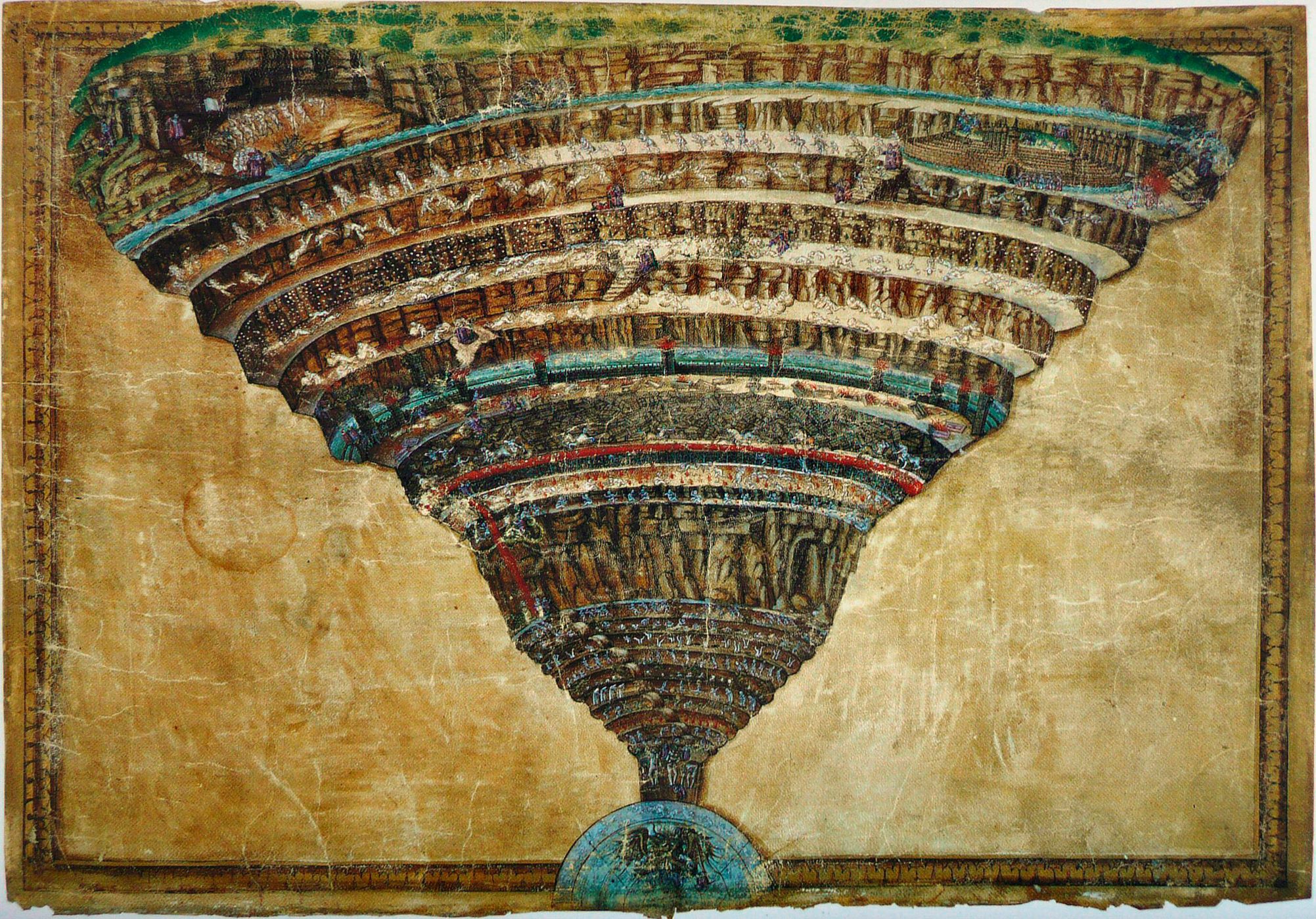

Thus, the first section covers the origins of Hell as the kingdom of Lucifer, the Final Judgment that condemns the damned to dwell eternally in Hell after their death on earth, the landscape of the infernal cone, the multiform nature of the Devil and the temptations with which he tries to attract us. Its itinerary begins with illuminations of Hell in medieval manuscripts, followed by fifteenth-century canvases of the damned being tortured by fire and brimstone, conical maps of Hell, 16th-century prints of Inferno episodes by Federico Zaccari and Giovanni Stradano, then several portraits of Dante (one is by the poet William Blake who also illustrated an edition of the Divina Commedia), and large 19th-century canvasses depicting Paolo and Francesca Da Rimini and Dante with Virgil.

The star of the exhibition is The Abyss of Hell (1481-88), a painting on parchment by Botticelli. On loan from the Vatican Apostolic Library only for the exhibition’s first two weeks, because of its fragility, then substituted by a facsimile. Other masterpieces here include: The Last Judgment by Fra Angelico, The Temptations of Saint Anthony Abbot by Brueghel the Elder, and the majestic 3-meter canvas Virgil and Dante in the Ninth Circle of Hell by Gustave Doré.

The second section is dedicated to the twentieth century. It opens with a Neapolitan puppet theatre (1920) with wooden pupi from Palermo and Catania on loan from the Antonio Pasqualino International Puppet Museum in Palermo. The pupi represent characters from Dante’s Inferno: several skeletons, devils, malagigi (epic heroes), a snake, dragon, killer whale and the sorceress Alcina.

The rest of the section illustrates man-made versions of Hell: the devastation of war, totalitarianism, the anguish of imprisonment, alienating and deleterious work on assembly lines or in pollution-causing factories, never-ending cities which transform farmland and forests into cement, thereby causing the extinction of flora and fauna, the darkness of madness in insane asylums with no hope of cure, the nightmare of extermination–in particular by the Nazis–and Islamic terrorism.

Several works in “man-made Hell” are “food for thought”, even if none “touch on Covid-19 as there is not yet enough detachment from the experience of isolation,” explained Clair in an interview with The Art Newspaper. “Nonetheless Inferno is timely because the century we’re living in has become Hell.”

Personally, I found von Stuck’s Lucifer, the exhibition’s logo, which is almost entirely black except for the devil’s fiercely-penetrating glazed blue eyes and a thin streak of light, to be truly spooky. It’s unclear whether the streak will close leaving the observer in total darkness and desperation with Lucifer or whether it will widen, offering the observer redemption. Repellant are the four plaster death masks of wounded First World War soldiers. Equally stomach–churning are Boris Taslitzky’s Le petit camp à Buchenwald (1945) and Fritz Koelle’s Hell (1997). Born in Paris to Russian emigrés, Taslitzky, a precocious artist and a left-wing member of the French Resistance, was arrested in November 1941 by the special brigades, a police force in Vichy France specializing in tracking down “internal enemies”. In July 1944 he was deported to Buchenwald, where he managed to draw 111 sketches of life in the Camp on stolen German paper. After his release in 1945, he painted this huge canvas of the horrors he’d experienced.

Koelle on the other hand, was interned at Dachau and later released. His bronze statue Hell, is a double self-portrait: a well-dressed Koelle, thanks to his release, carrying the naked, emaciated and dead Koelle he would have become had he been permanently interned.

Also deeply moving is the original proof of Se questo è un uomo (If this is a man) (1958) with notes by the author, Primo Levi, about his harrowing experience in Auschwitz. Especially disturbing to a New Yorker like me are Inferno’s last two sculptures: Raymond Mason’s Twin Towers Ablaze (2003) and Jake and Dinos Chapman’s Nein! Eleven (2012-13), two mounds of mixed media, meant to resemble the Twin Towers after meltdown.

The final section is dedicated to redemption, “not just that of Christianity,” recounts the press release, “but of every form of Humanism, to raise our gaze upwards–the universe, the infinite, the absolute, God. A gesture of poetic liberation and salvation that indicates the way to regain a new humanity far from the claustrophobic nightmares of Hell.” It includes paintings of the starry sky by Anselm Kiefer, ending with photographs taken by NASA’s telescope, “Ultra Deep Field”.

The splendid 479-page catalog, published by Electa in both Italian and in English editions (50 euros), contains many essays by distinguished international art historians, splendid photographs and a checklist of every artwork, and an anthology of excerpts about Hell from writings by Goethe, Leopardi, Victor Hugo, Baudelaire, Verne, Flaubert, Dostoevsky, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Malaparte, Thomas Mann, Solzhenitsyn and Calvino among others.