TMI. Meaning “too much information” this acronym was coined in the late ‘80s and soon became an Internet necessity as people used social media to share more personal information than others were comfortable with. One of the definitions on the Urban Dictionary site is, “Information more personal than anyone wants, or needs, to know. A common problem on the Internet.”

The examples used on the Urban Dictionary site are definitely too much information—and I won’t repeat them here. But suffice it to say if someone is describing a rash on a particular body part, it will most definitely result in the response, “TMI!!” Oversharing is a phenomenon that has blossomed across the platforms of social media, where anyone can sign up for a Facebook page, an Instagram account or a YouTube channel. There are more, of course, including Twitter, Reddit, Pinterest and the fast-growing TikTok app and all of them allow the users to share the most intimate details of their lives to anyone who is interested.

But what about the people who signed up for those accounts for less exhibitionistic motives? Angelo originally opened a Facebook account to get back in touch with his family in Italy. He also has a Facebook page for his therapy practice. I have a couple of Facebook pages myself—one is a personal account and one is my author page, where I post specifically about my books, my writing and my classes. Both of us share articles of interest, funny stories, pictures of our trips and vacations; and if pressed, I will admit to being more “sharing” than he is about the more personal aspects of our lives. Neither of us are the ones to explain in detail a recent medical procedure or the explicit actions of some dramatic transgression against us, but I am the one who will express anger, joy or solidarity with a topical or political issue. But I believe I have more of a reason to.

Since I published my first collection of essays and began writing for online magazines and websites, my life has literally been an open book. I am careful (I think) to respect my family’s privacy and don’t share anything they would find invasive, or maybe they’ve just gotten used to being mentioned in my observations on life and aging. Angelo definitely has—why do you think he agreed to writing this column together? But even I have a line—a boundary—which separates my so-called public life from my deeply private one, even though it might not appear that way to some.

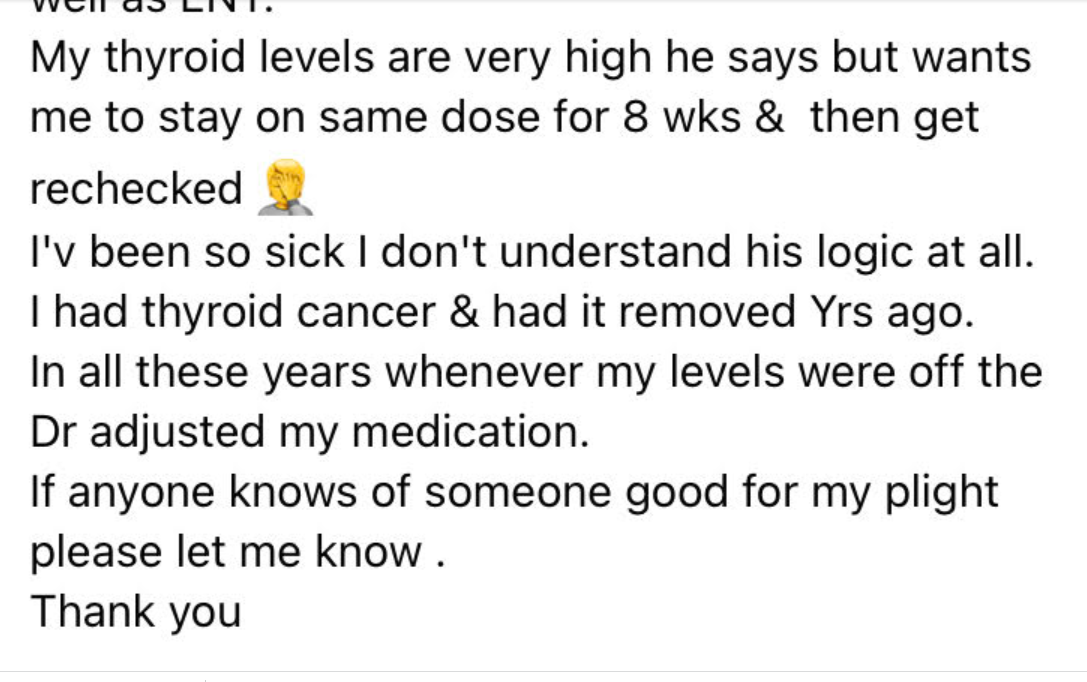

Recently, I posted about my daughter Annie’s cancer diagnosis. It took us all by surprise and was a huge blow, to put it lightly. Angelo cut short an extended trip Italy and I put off launching my writing program because the enormity of what we were facing was—well, we weren’t sure—but we knew we needed to conserve our energies and be available for the family. For me, sharing that kind of news felt right. For me, it not only gathered the love and support from family and friends far and wide, especially from those who might not have known otherwise, but it also opened up a channel for resources and information. One of the first comments on my Facebook page listed suggestions for dealing with the after effects of chemo sessions, most of which Annie put to use right away.

I also heard from an acquaintance who shared that she, too, had recently coped with a cancer diagnosis and the resulting treatment, fear and turmoil, but had not shared it with anyone. When she read my post, she said, it inspired her to share her own experience with friends. And then I noticed, a couple of weeks later, she posted her own message of fear and hope in the face such a terrible jolt. So, I felt good that my own sharing had a positive effect on someone else, besides me and my family.

To be clear, I ran this by Annie first. I didn’t share the details of her medical condition without making sure she was okay with it first. She does not share like I do. She is intensely private and has a sporadic presence on social media. I was glad that she did decide to share, for the same reasons I had—all sorts of support and love flooded back to her in the form of texts from old friends, bouquets of flowers, cozy and comfy treat bags and tons of books. She could read a book at each of the 20 weeks of chemo and still have a half a dozen or so left over. Friends are staying in touch and offering help…something that might not have happened without social media.

So, the good side: The findings of one study “demonstrated the potential usefulness of social media to keep tabs on evolving mental health issues. It also provides inspiration for potential interventions to address novel problems–such as loneliness–during COVID-19 pandemic.”

The #MeToo movement gained much exposure on social media and some say that helped others who were victims of sexual abuse find a community and a way to express—and address—their own experiences. Shared experiences online helped others feel less isolated, more empowered to come forward with their stories. And if not come forward, feel less victimized and afraid. However, sharing through such movements can also “have unexpected negative consequences, like shaming, security issues, or professional and personal conflict.” Another negative consequence in oversharing is in what a future employer might find out about you–and not like–online. According to the law website Nolo.com, “[surveys show] around 70% of all employers check out applicants on the Internet when hiring.” In fact, the Illinois Worknet Center posted an article on their website about oversharing and tips for “How to Avoid Oversharing.”

So what to do? Is all this sharing simply a craving for attention or a call for help? Is it beneficial or should we run screaming from all manner of social media outlets? It appears that, most likely, it’s both. In the vast world of the Internet, there is a place for everyone and everyone’s personal feelings about sharing. It comes down–as usual–to choice. And boundaries; your own, what you seek out online, what you pay attention to and what you scroll right past.